2. Key Concepts

- Oral Health

- Dental Caries

- Periodontal Disease

- Common Risk Factors Non-Communicable Diseases

- Oral Health Access

- Commercial Determinants of Health

- Public Health Prevention Interventions

- Oral Health Integration

- Universal Health Coverage

An entire section on Oral Health?

You may be asking yourself, why are we dedicating a section of the book to discuss oral health? Isn’t oral health related only to what is happening in your mouth? Are oral health diseases considered a public health issue? We hope to answer those great questions throughout the section’s content, so let’s start our discussion.

The connection between Oral Health and general health

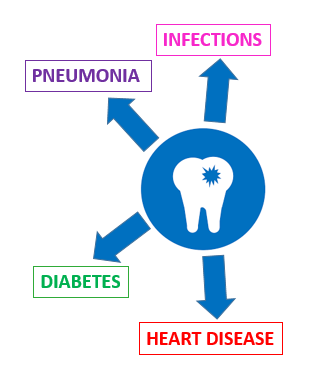

Poor care of the mouth can increase:

- Blood sugar levels in diabetics

- Seriousness of heart disease

- Risk of stroke

- Risk of aspiration pneumonia

- Risk of infections in other parts of the body

- Pre-term birth of baby

- Low-birth weight baby

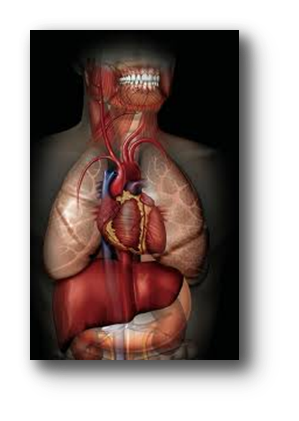

The mouth is often called the gateway of the body, not only because it is the main entrance of your digestive system but also your respiratory tract. That is why we often say that what is in the mouth does not stay in the mouth, and we are not referring only to food but also germs or bacteria. An infection in your mouth or a tooth can travel to other parts of your body, including your heart, lungs, and brain. Additionally, the mouth is sometimes called the sentinel of the body because many diseases can manifest first in your mouth. Therefore, as you see in the picture, the mouth is intrinsically connected to the rest of your body.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines Oral Health as “a state of being free from mouth and facial pain, oral and throat cancer, oral infection and sores, periodontal disease, tooth decay, tooth loss, and other diseases and disorders that limit an individual’s capacity in biting, chewing, smiling, speaking, and psychosocial wellbeing.”

WHO, 2021

The psychosocial and quality of life implications of poor oral health are worth mentioning. People with oral problems such as tooth pain have difficulty eating, speaking, concentrating in school and often are forced to take unpaid days off or miss school hours. All of these have social and economic impacts as people may develop low self-esteem, have reduced employability opportunities, experience disfigurement, and even death.

The Global Burden of Oral Disease

The following section adapted from WHO’s Oral Health

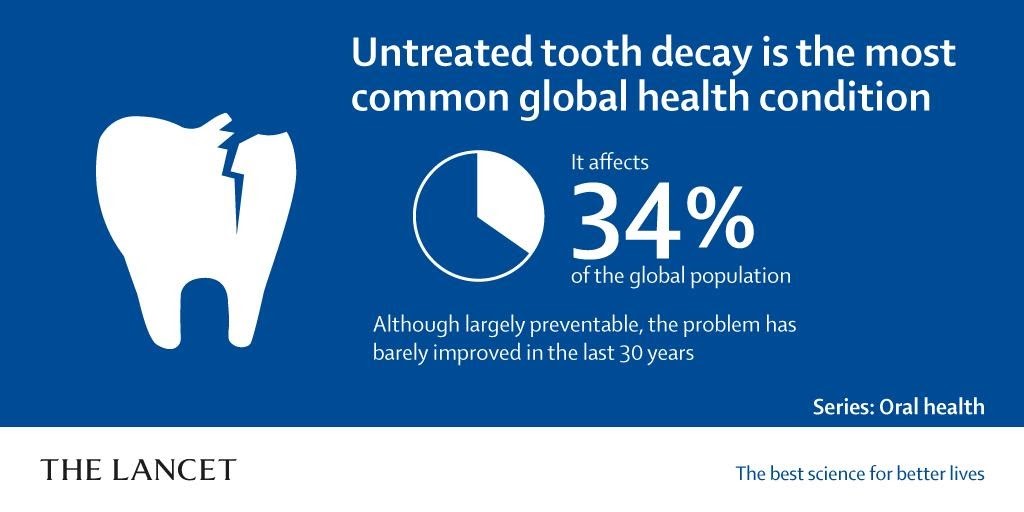

It is estimated that around 3.5 billion people worldwide suffer from oral diseases. The main oral health conditions affecting the population globally are dental caries (tooth decay), periodontal disease, oral cancers, oral manifestations of HIV, oral-dental trauma, cleft lip or cleft palate, and noma (a severe gangrenous disease starting in your mouth that is affecting young children mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa). Low and middle-income countries experience the highest-burden of oral diseases.

The good news is that the majority of oral diseases are ALL PREVENTABLE. In the section below, we will focus on some of the main oral diseases, and you can read about all other oral conditions mentioned above here.

Main Oral Diseases

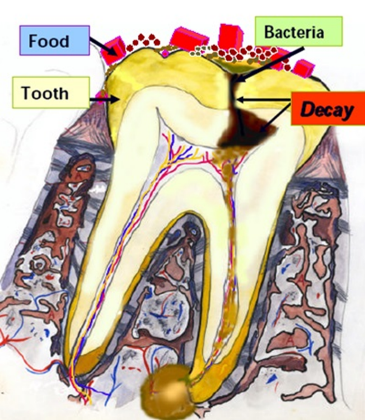

Dental caries (tooth decay or cavities) are bacterial infections that result when dental plaque (sticky film of bacteria) forms on the tooth. The bacteria uses the sugar you eat to produce acids that can destroy the tooth enamel over time, causing cavities. It is important to emphasize that once a dental cavity is formed, the only way to stop the advancement of the infection is by visiting the dentist. The dentist will remove the infected part of the tooth and fill it to stop caries and protect the nerve. Otherwise, the infection will continue advancing until it affects the tooth nerve and travels outside the tooth (see figure).

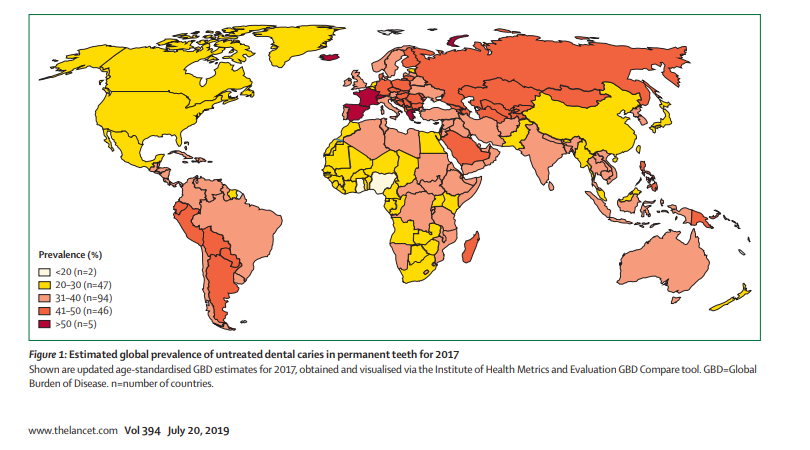

Dental caries are by far the most prevalent disease globally and the most common chronic disease affecting children worldwide, with approximately 530 million children suffering from caries of primary teeth (baby teeth). An estimate of 2.3 billion people suffer caries on permanent teeth.

The main causes of dental caries are high sugar intake, poor oral hygiene (brushing and flossing), and inadequate fluoride exposure in different forms. In the Surgeon General Report of 2000, Dr. David Satcher called dental caries the “Silent Epidemic” because it disproportionally affects low-income people, minority populations, and people of extreme ages (children and older adults).

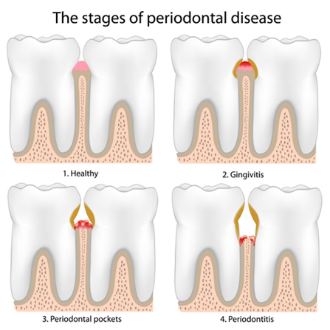

Periodontal (gum) disease is also a bacterial disease that initially causes the swelling of the gums (gingivitis) and, if not treated, advances to affect the bone surrounding the teeth (periodontitis). Over time, when the supporting bone is lost, the teeth can become loose and eventually fall out.

Around 10% of the global population is affected by severe periodontal disease. The main causes are poor oral hygiene (brushing and flossing) and tobacco use.

Oral cancer includes cancers of lips, tongue, other parts of the mouth, and oropharynx. There is variation around the world in the incidence of oral cancers going from 4 to 20 cases per 100,000 population. Still, statistics are showing that it is more common in men and older adults. You can explore here the incidence and mortality of lip and oral cancer worldwide.

It is important to add that Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infections are responsible for a growing percentage of oral cancer among youth in North American and Europe. The HPV vaccine, which is now available, attacks the most common types of papillomaviruses that cause throat cancers, protecting young people.

The regular use of smoke or smokeless tobacco combined with alcohol greatly increases the risk of developing oral cancer. The best practice is decreasing smoke or smokeless tobacco use and decreasing alcohol consumption, or quitting using the products altogether.

Global trends related to Oral Health

The following section is adapted from Harvard Global Health Starter Kit for Dental Education.

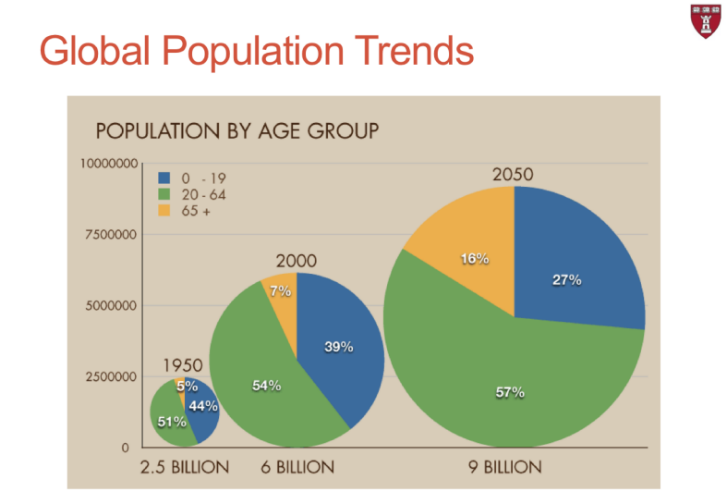

Let’s start this section by reflecting on population growth. Look at the figure below describing global trends. What do you see?

- Look at the size of the bubble from 1950, 2000, and 2050.

- What are the different colors in each bubble representing? (Age groups).

- Which age group is growing faster?

Interestingly, the global population doubled in only 40 years, from 3 million in 1960 to 6 billion by 2000. By 2050, for the first time in history, it is projected that the number of adults age 65+ will be more than the number of children under the age of 5 years in the world. Reflecting on these facts and the population trends, we can state that the global population is growing fast and increasingly aging.

With this in mind, let’s think about some of the concepts we studied in previous sections. As societies grow and prosper and urbanization increases globally, risk factors and determinants of health are evolving (think back to demographic and epidemiological transitions). As societies develop, the burden of diseases is also changing from having more communicable diseases (such as malaria and diarrhea) initially to having more non-communicable diseases (NCD) such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Nutrition and food patterns also change, with increased consumption of high-calorie, low-quality foods high in fat, sugar, and salt. In addition, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and sedentary lifestyles also increase. What do you think will be the effect of all these transitions in oral diseases?

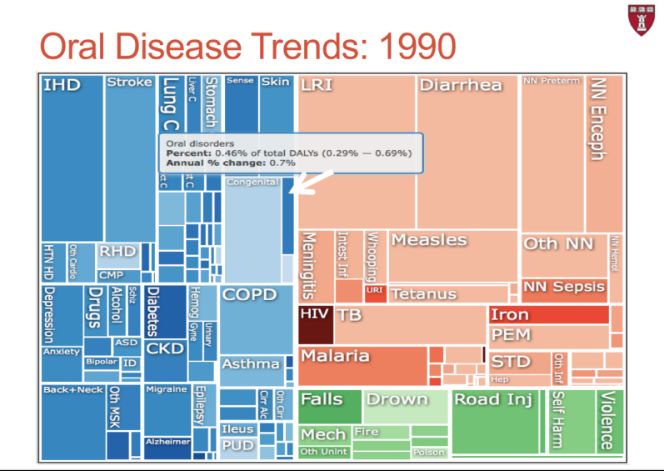

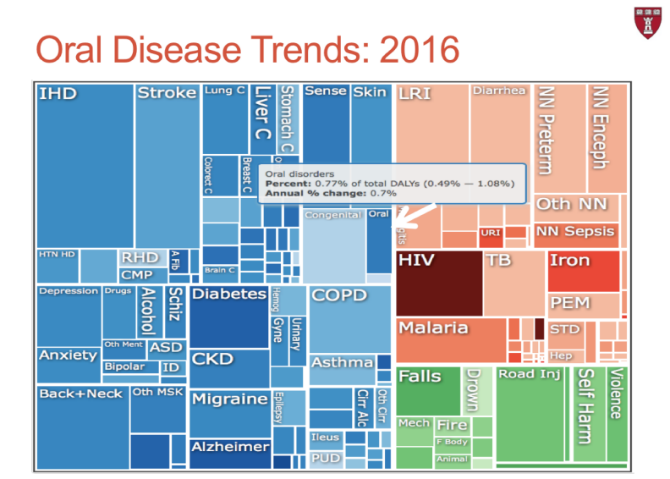

When we look at the classification of diseases we studied in the previous section and the three main disease categories we mentioned (communicable diseases (CD), non-communicable diseases, and injuries), oral disorders are considered part of the NCD category. Oral conditions in this category include dental caries, periodontal disease, edentulism (having no teeth at all), and other oral conditions.

Let’s look at the dimensions of oral diseases trends from 1990 to 2016. How has the size of the box changed from 1990 to 2016? What does this indicate? The larger size of the box in 2016 indicates an increase in the burden of oral disease rates over the years.

As we put all these concepts together and think about the implications for oral health, we can speculate that as the global population continues growing, with people living longer and experiencing increasing higher rates of NCDs, and as nutrition patterns are changing, increasing the consumption of sugary foods, the burden of oral disease is expected to continue rising.

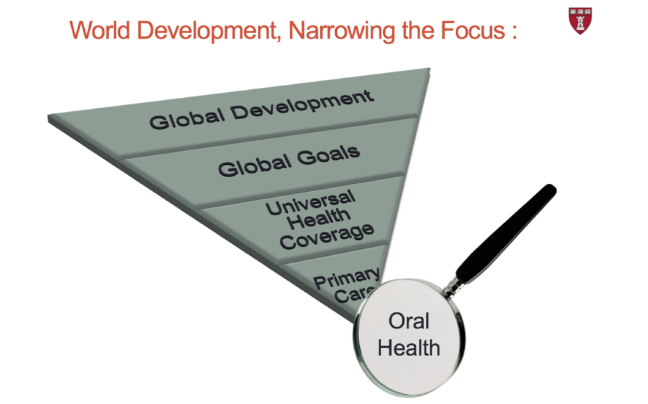

Integration of Oral Health into Global Health: Milestones

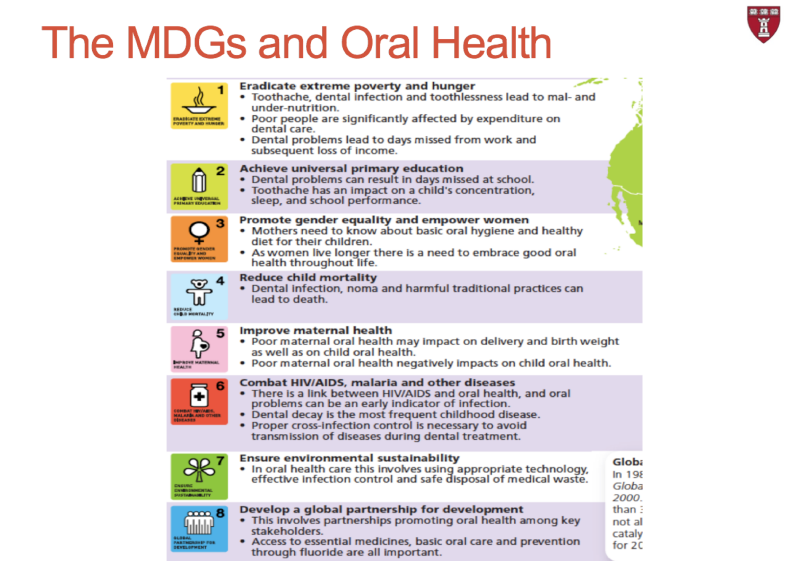

We study previously how the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been instrumental in helping world leaders to create a common agenda for poverty reduction.

Although none of the MDGs objectives and targets directly addressed the burden of oral diseases, all 8 MDGs had links to oral health (see MDGs and Oral Health figure). The most important part is that the development of the MDGs provided a valuable opportunity for oral health leaders globally to identify common linkages to align a global oral health agenda parallel to the MDGs.

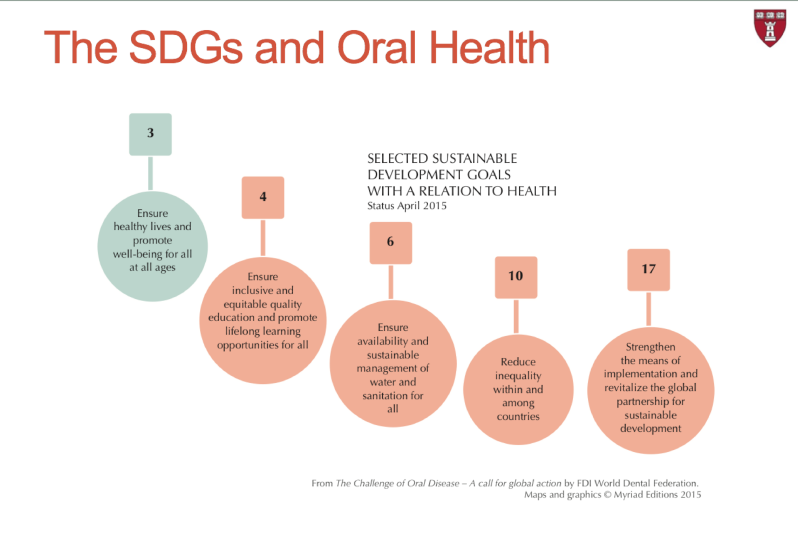

In the same way, when a new set of global goals emerged (SDGs) to carry forward the global sustainable agenda (MDGs 2000-2015; SGGs 2015-2030), global oral health leaders continued to draw links to oral health in their political and advocacy efforts (see SDGs and Oral Health Figure). These efforts to integrate MDGs, SDGs and oral health have paved the way for recognition to improve the political prioritizing of oral health at the global level.

On May 31, 2021, global oral health leaders achieved a major milestone when the 74th World Health Assembly adopted a resolution on oral health co-sponsored by 42 Member States and supported by many other countries and partners. The resolution calls Member States to develop a global oral health strategy, action plan, and monitoring framework to integrate oral health with Universal Health Coverage and the global NCD agenda by 2030.

Dr. Tedros: “Oral health has been overlooked for too long in the global health agenda. Fourteen years after the last consideration of oral health by EB60, today’s resolution provides a welcome opportunity to address the public health challenges posed by the burden of oral diseases to reposition oral health as part of the global health agenda.”

WHO’s Oral Health 2021 Resolution urges countries, taking into account their own national circumstances:

- to understand and address the key risk factors for poor oral health and associated burden of disease;

- to foster the integration of oral health within their national policies, including through the promotion of articulated inter-ministerial and intersectoral work;

- to reorient the traditional curative approach, which is basically pathogenic, and move towards a preventive, promotional approach with risk identification for timely, comprehensive, and inclusive care, taking into account all stakeholders in contributing to the improvement of the oral health of the population with a positive impact on overall health;

- to promote the development and implementation of policies to promote efficient workforce models for oral health services;

- to facilitate the development and implementation of effective surveillance and monitoring systems;

- to map and track the concentration of fluoride in drinking water;

- to strengthen the provision of oral health services delivery as part of the essential health services package that delivers universal health coverage;

- to improve oral health worldwide by creating an oral health-friendly environment, reducing risk factors, strengthening a quality-assured oral health care system, and raising public awareness of the needs and benefits of a good dentition and a health mouth.

(WHO, 2021)

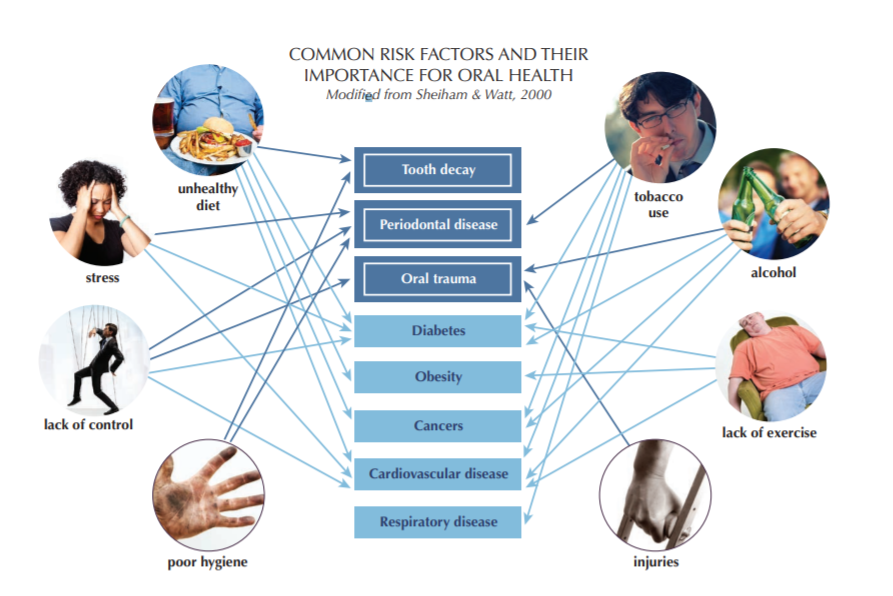

Common Risk Factors for Non-communicable Disease

The most common non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including oral disease, share the same social determinants and several other common risk factors (see figure). Modifiable risk factors such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and an unhealthy diet high in free sugars are common to the four leading NCDs (cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, and diabetes) as well as to oral diseases. Especially important, the effect of unhealthy diets and tobacco use.

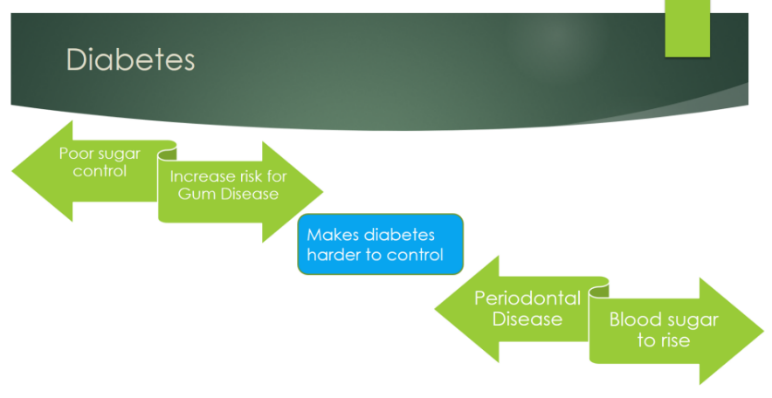

In addition, it is reported that diabetes is linked reciprocally with the development and progression of periodontal disease. Moreover, there is a causal link between high sugar consumption and diabetes, obesity, and dental caries.

For these reasons, oral health leaders collaborating with WHO in their Draft Global Strategy on Oral Health urge countries to integrate efforts and align strategies to intentionally address oral diseases with other NCDs (WHO, 2021).

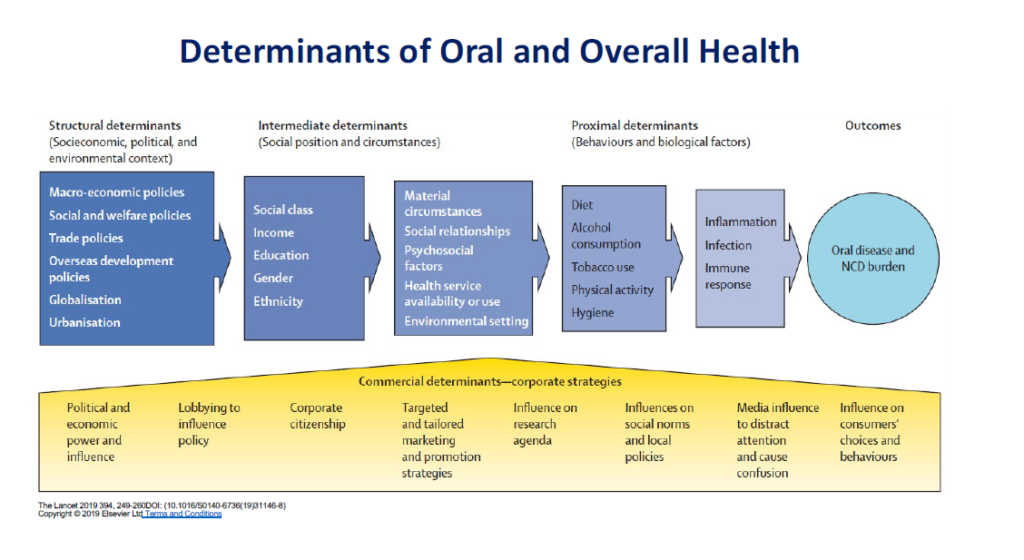

Oral Health and the Determinants of Health

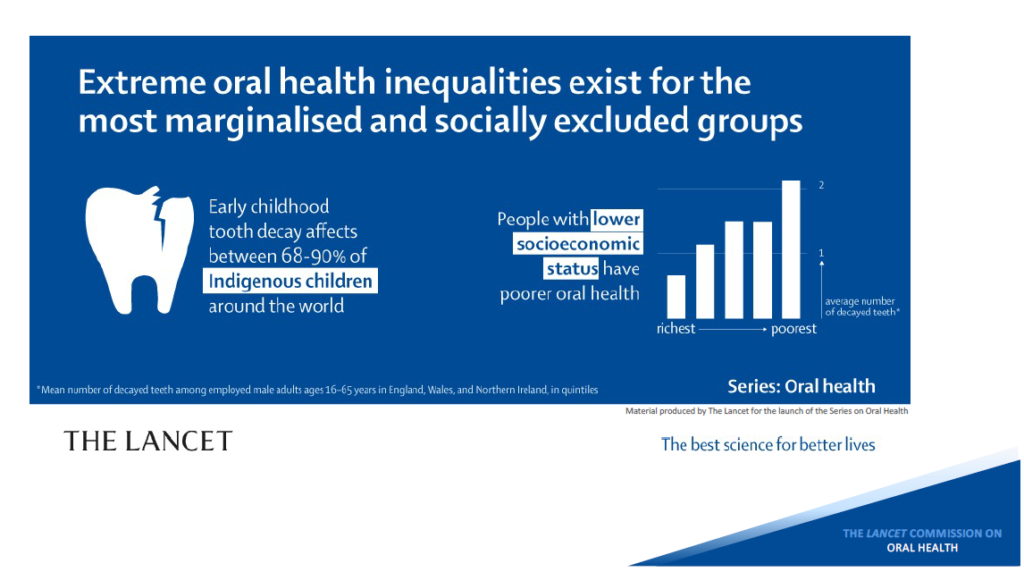

As with many other health conditions, oral health disparities emerge from unequal social, political, financial, and environmental resources. The unequal distribution of resources and opportunities accounts for the persistent differences in oral health status and the burden of oral diseases for low-income populations. This association exists through the life course from early childhood to older age and across populations in high-, middle- and low-income countries.

There is a very strong and consistent association between socioeconomic status (income, occupation, and educational level) and the prevalence and severity of oral diseases and conditions. Across the life course, oral diseases and conditions disproportionally affect the poor and vulnerable members of societies, often including those who are on low incomes, people living with disability, refugees, prisoners and/or socially marginalized groups.

WHO, 2021

The personal consequences of untreated oral health conditions among our most vulnerable populations are severe. They include physical symptoms (pain), functional limitations, isolation, and impacts on their social and emotional wellbeing. In addition, those who somehow can pay for any oral health treatment can carry a significant economic burden. In 2015, worldwide, oral conditions accounted for US$357 billion in direct costs and US$188 billion in indirect costs, with large differences between high, middle, and low-income countries (WHO, 2021).

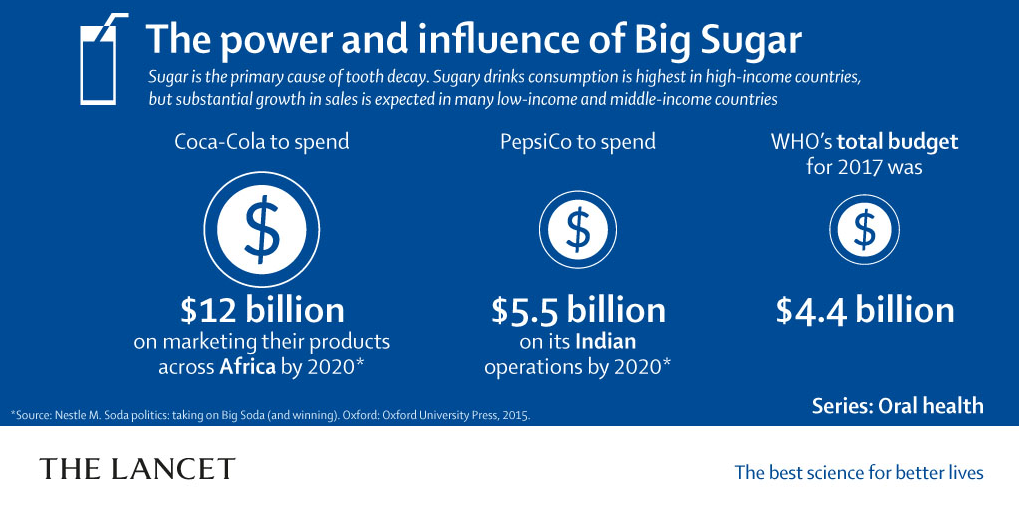

Commercial Determinants of Health (CDoH) are defined as “the strategies and approaches used by the private sector to promote products and choices that are detrimental to health.”

WHO, 2021

CDoH is of increasing importance as they closely relate to many oral health conditions. Some examples include promoting all forms of tobacco and alcohol use and the promotion of unhealthy food consumption, including promoting the high consumption of sugar. Particularly challenging for improvements in oral health is the influence of the global sugary industry. Some of the tactics the sugary industry use include discrediting major research and recommendations on diet and nutrition, enlisting the support of important public officials to block reports and policies and funding independent organizations to get access to decision-makers and to diminish the role of sugars in the etiology of diseases (The Lancet, 2019).

Authors from the Lancet Oral Series proposed a conceptual framework combining social and commercial determinants of oral health that graphically summarize the interacting processes and influences of all these factors (The Lancet, 2019).

There is currently limited research on the impact of CDoH, but attention is increasingly growing on understanding how corporations, industries, and political practices are affecting the global drivers of ill health. This approach offers a unique opportunity for oral health. It shifts the dominant paradigm in public health where individuals are solely responsible for their choices and consider the important impact of inadequate environments in population health. In this approach, health and social inequities and continued damages to the global environment could be understood and addressed in the light of CDoH (Mialon, 2020).

Watch the interesting perspective that a dentist gives in this short TED Talk related to this topic in the following video.

The Importance of Prevention

A common approach to reducing the burden of oral disease and other NCDs should address common risk factors through public health interventions.

These interventions include:

- The promotion of a well-balanced diet includes a high intake of fruits and vegetables and low consumption of sugars. If possible, promote the preference of fluoridated water (tap water) as the main drink at the same time.

- Stopping the use of ALL forms of tobacco, including vaping

- Reducing alcohol consumption

- Encouraging the use of protective equipment, such as mouth guards, when practicing contact sports or other equipment when traveling on bikes and motorcycles

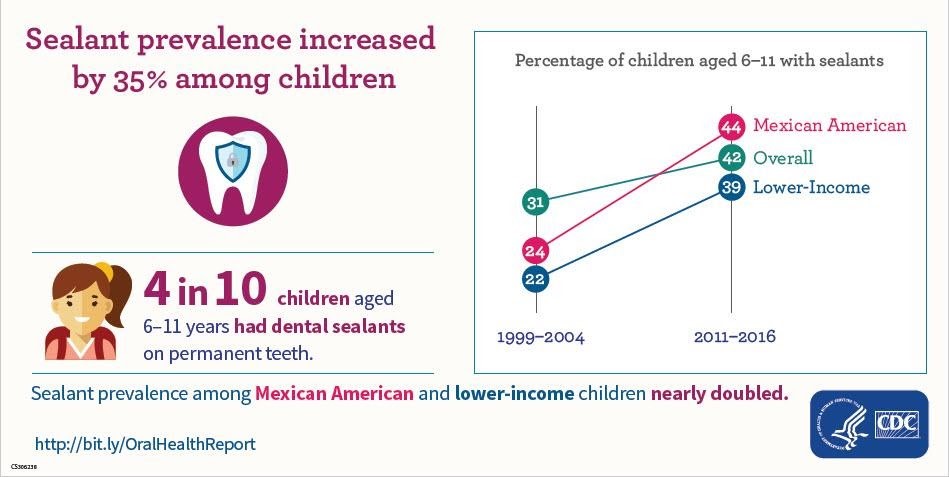

Two important public health interventions have helped reduce the incidence and prevalence of dental caries in the last decades, especially in children and low-income populations, the use of fluoride in its different forms and the application of dental sealants in the chewing surfaces of back teeth.

Use of Fluoride to prevent dental cavities

Fluoride is a mineral that helps strengthen the enamel of the teeth and fight dental caries. It can be found in public water supplies (tap water), salt, milk, toothpaste, mouthwash, and other dental products. Fluoride can help repair the early stages of tooth decay before we can even see a cavity. Adequate fluoride exposure is an essential factor in the prevention of tooth decay. Brushing teeth at least twice daily with a toothpaste containing fluoride and drinking tap fluoridated water should be encouraged.

Read some interesting facts about community water fluoridation here.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) named Fluoridation of drinking water as one of the ten greatest achievements in public health in the last century (1990-1999).

Fluoridation of drinking water began in 1945 and in 1999 [reached] an estimated 144 million persons in the United States. Fluoridation safely and inexpensively benefits both children and adults by effectively preventing tooth decay, regardless of socioeconomic status or access to care. Fluoridation has played an important role in the reductions in tooth decay [in the United States] — from 70% to 40% in children — and of tooth loss in adults — from 60% to 40%.

CDC, 1999

In the United States, approximately 200 million (73%) of the population in 2018 was served by community water systems with enough fluoride to protect teeth. If you are curious to know if your water system is incorporating enough fluoride to prevent cavities, go to My Water’s Fluoride to find out. The goal for 2030 is to have at least 77% of Americans serve fluoridated water (CDC, 2018).

But what other alternatives do we have to bring the benefits of fluoride into populations that are not served by community water systems?

Read Preventing Dental Caries in Jamaica, a successful global health story from the Millions Saved collection (Center for Global Health Development, n.d.).

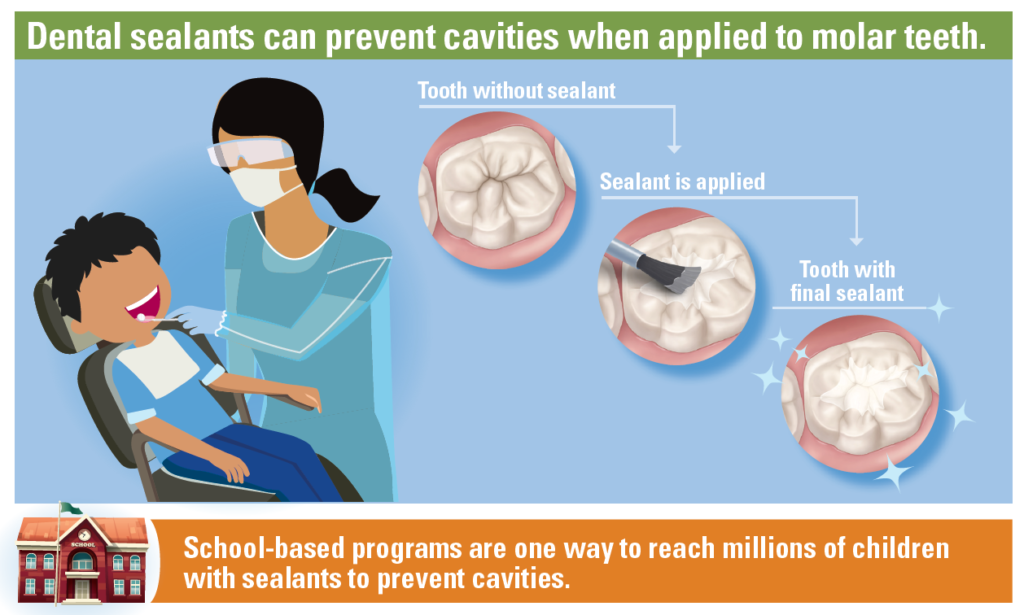

Dental Sealants

Dental sealants are a painted coating that dental professionals apply into the chewing surfaces of back teeth (molars), sealing the grooves and preventing bacteria from attaching in those indentations to develop cavities.

Dental sealants help prevent around 80% of cavities in the back teeth, where 9 out of 10 cavities occur (CDC, 2021). School-based Dental Sealant programs are one of the most effective ways to deliver this preventive intervention; however, they are underused. In the U.S., 4 out of 10 children between 6 and 11 years had a dental sealant on permanent teeth. The lower rates are usually found in low-income (22%) and Mexican American (31%) children (CDC, 2004). However, in the last decade, a significant increase has been seen in the use of sealants for Mexican American (44%) and low-income (39%) children due to the expansion of school-based sealant programs.

Access to Oral Health Services

The major factors defining the unequal distribution of oral health resources are related to major limitations of the current oral health care system, and these include:

- A mismatch between the need and the availability and location of services

- Dental treatment (drilling) focus instead of prevention focus

- Current dental silo in regards to other medical services

- Payment system incentivizing curative treatment instead of valued based

- High cost of dental services

- Workforce issues (dentist centered) discouraging delegation within the dental team

(Lancet Commission on Oral Health, 2019)

Let’s watch a video that puts into real-life perspective the limitations of oral health care access.

As we saw in the Hidden Pain video, there is an urgent call for radical reform of the current oral health care system switching from an interventionist (biomedical) focus to a population health focus. The Sustainable Development Era is calling us toward Universal Health Coverage and the integration of oral health into primary care. Let’s look into more detail into these concepts.

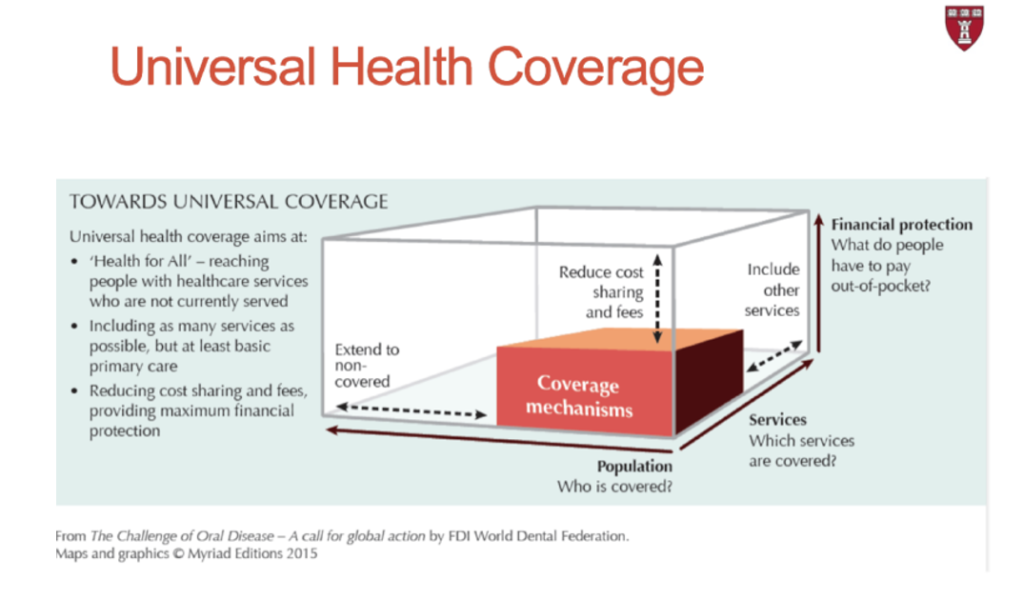

Universal Health Coverage means that all people have access to the health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship. It includes the full range of essential health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care.

WHO, n.d.

The section to follow was adapted from the Harvard Global Health Starter Kit for Dental Education.

There are three dimensions of Universal Health Coverage:

- Who is covered? The percentage of the population covered

- Which services are covered? The percentage of services/treatments covered by the prepaid cost

- What do people have to pay out-of-pocket? The percentage of costs that are prepaid/covered and the percentage that are not

The overall aim of universal health coverage is to reach as many people as possible with essential health services, especially those who otherwise do not have access to care, and include coverage of as many health services as possible. These aims will assist in reducing out-of-pocket spending on health care by individuals, especially those who cannot afford it.

As we reviewed in a previous section, the Declaration of Alma Ata (1978) created a shift in how we think about health and healthcare.

Key aspects of Primary Care (Alma Ata Declaration):

- Whole health vs. priority disease

- Balance between preventive and curative measures

- Ongoing patient-provider relationship

- Health of community members over their lifecycle understanding disease determinants

The focus and values of primary care should be placed on whole-person health over the course of their lifetime through ongoing patient-provider relationships and a proper balance between prevention and clinical care. The different approach has resulted in a stronger focus on health equity by global leaders, governments, and local organizations.

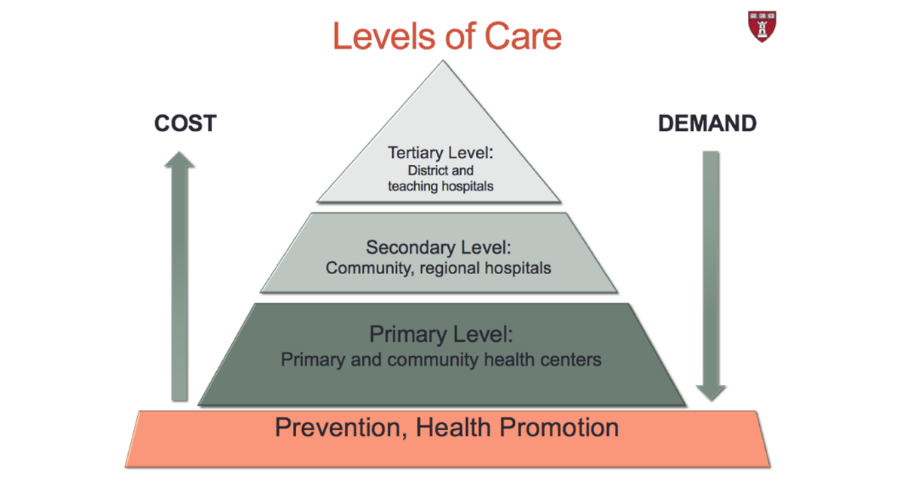

To achieve this, a well-functioning health system is necessary where the cost of care to people is minimal, and the cost to the health care system is reduced through a tiered approach to care delivery.

The system’s foundation should rest on prevention and health promotion, which will mitigate the cost by addressing preventable diseases before they occur and sustain these cost reductions through ongoing health promotion efforts.

When preventive efforts are not enough and individuals show preliminary signs of illness or are at higher risk of illness, they can get sick early in primary care centers. More advanced care is available to hospitals by specialists when early clinical care is insufficient, and other specialized care is available as needs progress at district and university hospitals. In this ideal model, while cost increased at each tier, demand for services should decrease.

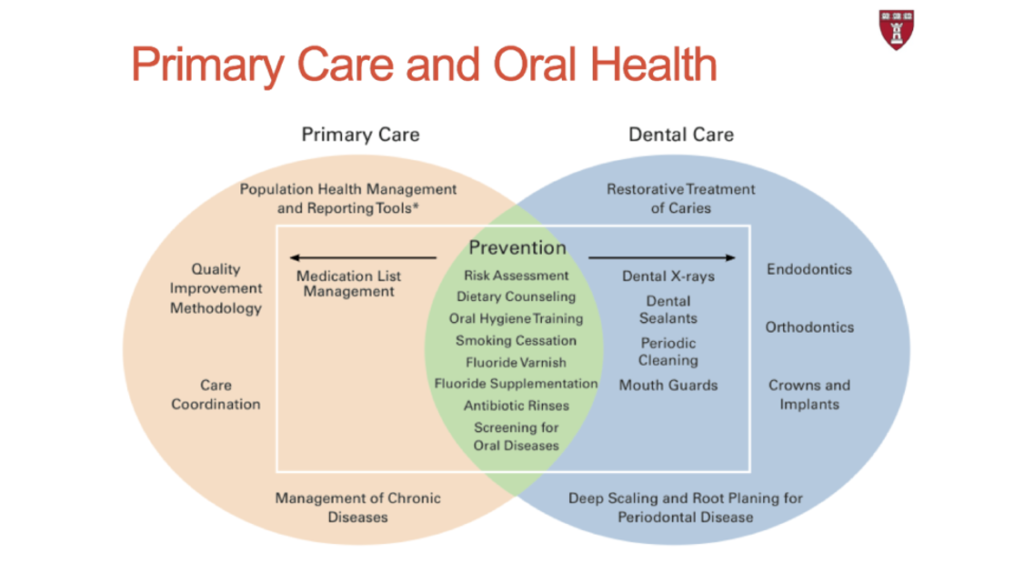

The integration of oral health into primary care is a huge task that will require a substantial shift in how we think about paying and financing oral health services and how to develop a dental workforce that truly addresses the needs of communities, including changes in education and scope of practice, as well as policy.

There is currently a natural overlap between key concepts of primary care and dental care (more appropriately named oral health care because it implies more than just the teeth). The overlap rest mainly on primary and secondary prevention. Dental professionals are currently trained to deliver services emphasized in the blue bubble, with a strong focus on curative care.

Some important considerations to achieve medical-dental integration will be the use of alternative dental workforce models that include shifting preventive and some clinical tasks to be delivered by other professionals such as a dental therapist, dental nurses, community dental health coordinators, community health workers, nurses, and physicians, with improving communication among and between providers. Oral health care reimbursement may come through medical insurance instead of separated dental insurance promoting integration. Non-dental professionals will receive oral health training, and the dentist will receive stronger medical training. Stronger integration of medical and dental care in a different health care setting is increasingly happening.

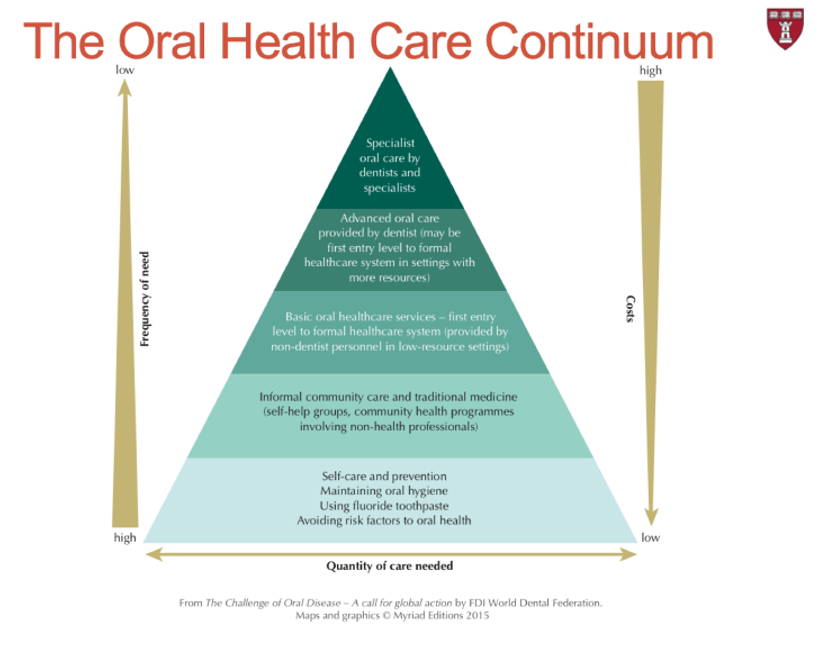

The FDI, in their Oral Health Atlas, illustrated the Oral Health Continuum of Care with the objective to beginning dissolving boundaries between oral health and medical care, illustrating an ideal system where efforts are cost-effective, focusing on where the greatest needs are, and reducing the amount of specialized care needed.

Let’s finish this section by watching a short video about the impact of a dental therapist in Alaska.

“Because oral health disparities emanate from the unequal distribution of social, political, economic, and environmental resources, tangible progress is likely to be realized only by a global movement and concerted efforts by all stakeholders, including policymakers, the civil society, and academic, professional, and scientific bodies.” (Lee, 2014)

References

Center for Global Development. (2004). Millions Saved, Case 18. Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/archive/doc/millions/MS_case_18.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Ten Great Public Health Achievements — United States, 1900-1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056796.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Dental Sealants Infographic. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infographics/dental-sealants-tabs.html#tabs-1-2

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Community Water Fluoridation. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Oral Health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/pdf/communitywaterfluoridationfactsheet.pdf

Global Oral Health Interest Group of the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH). (2018). Toward Competency-Based Best Practices for Global Health in Dental Education: A Global Health Starter Kit. (B. Seymour, J. Cho, & J. Barrow, Eds.)

Lee, J. Y., & Divaris, K. (2014). The ethical imperative of addressing oral health disparaties: a unifying framework. Journal of Dental Research, 93(3), 224-230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034513511821

Mialon, M. (2020). An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00607-x

Peres, M. A., Macpherson, L., Weyant, R., Dary, B., Venturelli, R., Mathur, M. R., . . . Watt, R. G. (2019). Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet, 394(10194), 249-260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8

Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly. (2021, May 31). Oral Health Resolution. Agenda item 13.2. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74/A74_R5-en.pdf

The Oral Health Atlas. (2015). The Challenge of Oral Disease – A call for global action. Geneva: FDI World Dental Federation. Retrieved from https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/complete_oh_atlas-2_0.pdf

World Health Organization. (2021). Retrieved from Whos Oral Health Fact Sheet: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health

World Health Organization. (2021, August 9). WHOs Global Strategy on Oral Health. Retrieved from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/india/health-topic-pdf/noncommunicable-diseases/draft-discussion-paper–annex-3-(global-strategy-on-oral-health)-.pdf?sfvrsn=aa03ca5b_3&download=true

World Health Organization: International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2020). World Health Organizatios. Retrieved from Lip Oral Cavity Fact Sheet: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/1-Lip-oral-cavity-fact-sheet.pdf