Key Concepts

- Social Determinants of health

- Structural determinants of health

- Social ecological model of health and health behavior

- (In)equality

- (In)equity

- Health disparities

- Social cohesion

- Direct costs of health services and healthcare

- Indirect costs of health services and healthcare

- Health Literacy

Prelim Engagement

If someone were to ask you, ‘What causes a person to become sick?’ --- how would you respond? Is disease caused by germs and viruses? Genetics, sex or age? What would you say if someone said that your zip code (address) plays a significant role in predicting and determining your health status and well-being?

As the previous sections demonstrated, the burden of disease (communicable disease, non-communicable disease, mental health and injuries) is not distributed equally around the world. You have seen the great differences in health outcomes between regions, countries and within countries and communities.

This section of learning and engagement will push you to think about the determinants (or causes) of disease and health differently than you have perhaps thought about them in the past. We are going to look beyond germs and genetics and think about other factors in our lived environment and social structures which have profound effects on health behaviors and health outcomes.

1. Let’s begin by thinking about those differences between health outcomes that we observed in the last sections. What are differences in health outcomes between regions and countries and within countries and communities called? We will start with an introduction to the concept of health equity from the short video below.

2. What do we call, then, determinants of health which go beyond biological determinants such as genetics, sex and age? This video will introduce you to one of the most significant Public and Global Health concepts you will learn this term.

3. So now that you know a little bit more about the social determinants of health, do you think the physical location of a person’s home and the community they live in could say something about their life expectancy? This news article and news video clip discuss the 30 year life expectancy difference between two of Chicago’s neighborhoods located just 9 miles apart.

Screenshot source: Chicago Tribune, link below. Photo: Lou Foglia/ Chicago Tribune.

LINK TO SHORT CHICAGO TRIBUTE ARTICLE TO READ:

LINK TO VIDEO CLIP DISCUSSING LIFE EXPECTANCY DIFFERENCES IN CHICAGO:

What causes someone to become sick?

Why are certain populations healthier than others?

Why do some populations have higher rates of diseases than others?

Would you say germs? Viruses? Health behavior choices? Sex? Age? A combination of these factors?

What would you say if you were told your zip code (the neighborhood where you live) can be a major predictor and determinant of your health outcomes?

As we have seen in the previous sections, the burden of disease for communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases and injuries is not equally distributed around the world. Troubling differences in health outcomes exist between world regions, between countries, within countries — and even within individual cities.

For example, do you know what the life expectancy is for someone living in the northern and central (Loop) neighborhoods of Chicago, Illinois? What about someone in the south of the city?

A study in 2012 found that from 2003-2007 life expectancy in the city of Chicago varied greatly depending on zip code and income (Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Health Policy Institute, 2012).

Look at the map below. The darker areas indicate neighborhoods where residents were not expected to live beyond the age of 70 years; in the lighter areas residents are expected to live up to 90 years. The residents in the south, southeast and west of the city predominantly identify as African American and Latinx.

This same study found that people living in communities in the city of Chicago with a median income higher than $53,000 had a life expectancy up to 14 years longer than people living in Chicago communities with a median income below $25,000. From the news article you were asked to read for this section’s Prelim Engagement, we learned that data from 2010-2015 showed a 30 year life expectancy gap between Chicago neighborhoods in the north and downtown and the southeast and west (Schnecker, 2019).

How is this possible? How is this fair?

Darker areas indicate lower life expectancy.

Source: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Health Policy Institute (2012).

Understanding inequality, inequity & health disparities

You have probably heard of the terms inequality and inequity at some point in your classes, on the news, from social movements or in legislation. While these terms are often used interchangeably, there is an important distinction between the two, especially in the fields of Public and Global Health.

Health inequality refers to differences in health status between different population groups. In public and global health we expect to observe some differences in health status between different populations.

For example, differences in mobility between elderly people and younger people or differences in breast cancer rates by gender.

(WHO, n.d.)

What makes a health inequality — an observed difference in health status between populations — a health inequity?

Health inequities are differences in health status or access to the resources needed to achieve optimal health which are:

– Avoidable

– Unfair

– Unjust

(Healthy Equity Institute, 2019)

So, from these definitions we can say that many health inequalities point to health inequities, but not all health inequalities are inequitable.

For example, we expect to see a difference in breast cancer rates between women and men as women are, biologically, more susceptible to this type of cancer. This difference in health outcomes is considered a health inequality.

However, what if we found that in one of Chicago’s high income zip codes breast cancer rates in women were below the national average but in one of Chicago’s low income zip codes rates were four times higher than the national average? Would this difference seem avoidable, unjust and unfair?

Think back to the differences in life expectancy between Chicago neighborhoods — do you think these differences are examples of just health inequalities or, are they also examples of health inequities?

Ask yourself — Are the differences in life expectancy between the neighborhoods of Streeterville and Englewood:

You can actually find the incidence of all cancers by zip code in the state of Illinois at the Illinois Department of Public Health’s website here. If you’re interested, look at the invasive breast cancer incidence rates for the zip codes 60620 and 60610. Knowing what you know about the differences in life expectancy between the Englewood and Streeterville neighborhoods, which zip code do you think is which neighborhood? This is the kind of comparative data epidemiologists use to explore patterns of disease, identify health inequities and develop interventions to address them.

- Avoidable?

- Unfair?

- Unjust?

If you answered ‘yes’ to all three (hint hint, ‘yes’ is the right answer!) then, yes, differences in life expectancy between neighborhoods in Chicago are considered health inequities.

Health inequities are at the root of what are known in Public and Global health as health disparities.

Health disparities are preventable differences in health among groups of people including burden of disease, injury, violence or access to any opportunity to achieve optimal health experienced by socially disadvantaged racial, ethnic, and other population groups, and communities.

(CDC, 2017)

If you did not watch this video during the prelim engagement, watch it now. If you already watched it, watch it again! This video explains the important concepts of health (in)equity, health disparities and the factors that contribute to differences in health outcomes between populations in more detail. We will return to the concepts of (in)equality, (in)equity and health disparities throughout this course!

Understanding the social determinants of health and well-being

Communicable diseases are caused by infectious agents, like coming into contact with bacteria or a virus. If you have a family history of a non-communicable disease like diabetes or cancer you may be at a genetically higher risk of developing that disease. Individual behaviors, like smoking, can also increase your risk of certain diseases. And, as we age, we may face more challenges with mobility or become more susceptible to certain diseases.

While all of these biological, genetic and individual behavior factors do contribute to disease and poor health, health inequities and health disparities like those observed between Chicago neighborhoods cannot be explained by the presence of infectious agents (ie bacteria, viruses), individual characteristics (ie genetics, sex, age) or health behaviors (ie smoking, substance use, eating habits, exercise) alone.

So, what does explain these striking — and avoidable — differences in health outcomes between populations within and between countries around the world?

To start this conversation, let’s watch this short intro video looking at underlying causes of health inequities in the United States. (Note: This clip was produced in 2008 so statistics are outdated, but key concepts are still very relevant!)

The social determinants of health are one of the most important concepts you will learn about in this course. The social determinants of health form the lens through which we understand health, well-being, illness and disease in the fields of public and global health.

But, what exactly do we mean by the social determinants of health or SDOH?

The social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in places where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes.

(CDC, 2021)

There are a number of ways to understand, break down and categorize the SDOH. Different organizations and authors use different frameworks to understand this important concept, so do not be surprised if you see the SDOH represented in various ways in this class or by different Public and Global health agencies and actors.

On the most basic level, we can understand the social determinants of health as falling into three categories:

- Social

- Economic

- Environmental

Keep in mind that SDOH can be either positive or negative.

SDOH can also exist or occur at different levels (see Determinants of Health image below):

- Individual

- Community

- Societal or structural

Source: Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991.

Can you think of some examples of determinants of your health, both positive and negative, on each of these levels?

For example, positive determinants of health on the individual level might be exercising daily, making sure to schedule your yearly dental appointments or eating healthy food.

However, the determinants of health framework also shows us that individual behavior choices are often affected by other factors. As you move out from the individual, you see that factors that affect the individual’s ability to make positive healthy choices can be largely out of individual control.

Look at the image of the Determinants of Health above.

- What factors at the Social and Community level might affect, for example, your ability to exercise daily?

- For example, does your neighborhood have sidewalks or public parks within walking distance? Are you be able to exercise around your house easily and safely?

- What about on the wider Societal or Structural levels, including policies, cultural norms and practices, and environmental conditions?

- For example, is the minimum wage in your city a living wage that enables you and your household to pay rent? Do you have to work more than one job to meet basic needs? Do you have enough time after work to exercise everyday?

Think about another example like eating nutritious food. As you watch this video about barriers to nutritious food access in Washington, DC think about which factors on the individual, social and community, and societal and structural levels could affect your ability to eat nutritious food if you lived in this neighborhood. How does this neighborhood in Washington, DC compare to your own neighborhood?

Let’s start to make some connections as well — how does (unequal) access to nutritious food affect, for example, health outcomes and health disparities like the differences between life expectancy we discussed earlier?

Different dimensions of the Social Determinants of Health

As mentioned, there are a number of ways that public and global health actors understand, categorize and name the SDOH.

For example, the image below from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention breaks the SDOH down into five domains:

- Economic Stability

- Education Access and Quality

- Health Care Access and Quality

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

- Social and Community Context

Source: Healthy People (2030)

For every SDOH framework you come across, try to think of how the different SDOH might operate — positively or negatively — on each level of influence (individual, social and community, and societal/ structural).

Watch the video below for an in-depth explanation and understanding of the SDOH using a framework developed by the WHO. You may want to watch this one twice — this is a big takeaway message from this section!

Note: As mentioned above, there are a number of frameworks which represent the SDOH in different ways. For example, you will see in the video below that the WHO SDOH model includes a term / level of determinants called Intermediary Determinants. In this course we will not use that specific term to discuss the SDOH, but it is important to be able to look at, process and critique different models and how they talk about the SDOH.

Think back to our discussion in Section 1.1: What is Global Health? about different ways of thinking about and conceptualizing health. Reflect on the definitions of Indigenous Health we reviewed.

Indigenous peoples’ concept of health and survival is both a collective and an individual inter-generational continuum encompassing a holistic perspective incorporating four distinct shared dimensions of life. These dimensions are the spiritual, the intellectual, physical, and emotional. Linking these four fundamental dimensions, health and survival manifests itself on multiple levels where the past, present, and future co-exist simultaneously

(Committee on Indigenous Health, 1999)

Indigenous Health theories, models, and practices often have a deeply relational character: the well-being of individuals is intimately bound with the well-being of others, both human and other- or more-than-human.

(Henry, LaVallee, Van Styvendale and Innes, 2018)

Given Indigenous people’s framing of health, can you think of how Indigenous conceptualizations of the SDOH might differ from the SDOH models we have discussed so far?

As we also discussed, there is no one conceptualization or definition of Indigenous Health. Each Indigenous community and population will have their own specific way of defining their relationship to health, what constitutes and what determines health and well-being.

For one perspective on the SDOH from a First Nation Perspective, watch this video from a Public Health leader of the Ktunaxa nation in the territory known as British Columbia, Canada. As you watch this video, take a close look at the image of the SDOH as understood by the Ktunaxa people.

How does this differ from the western models above?

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aD-wYpDsooQ

Source: Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991)

Source: Healthy People 2030a, n.d.

Going deeper: The Structural Determinants of Health

During the video above by the WHO on the SDOH, you heard the term structural determinants of health as part of the WHO’s SDOH framework. A frequent criticism of some western SDOH frameworks, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s image above, is that they do not explicitly highlight the structural determinants of health.

Think of the structural determinants of health as at the ‘root’ of health inequities. Structural determinants of health ‘shape’ or determine the quality of the SDOHs experienced by different people, neighborhoods and communities (IDPH, n.d.).

Review the different models of the SDOH above — does one address the structural determinants of health more than the others?

Structural determinants of health are the ‘root causes’ of health inequities, because they shape the quality of the Social Determinants of Health experienced by people in their neighborhoods and communities.

The structural determinants affect whether the resources necessary for health are distributed equally in society, or whether they are unjustly distributed according to race, gender, social class, geography, sexual identity, or other socially defined group of people

(Illinois Department of Public Health, n.d.)

The structural determinants of health can include factors such as:

- The governing process

- Voting

- Legislation

- Carceral system (criminal justice system)

- Economic and social policies that affect

- Pay

- Working conditions

- Access to and quality of housing

- Access to and quality of education (IDPH, n.d.)

- Access to and quality of food

Structural inequities occur because of the systemic discrimination embedded in the structures of a given society. Think of the ‘-isms’ — such as racism, sexism, classism, able-ism, homophobia, transphobia, colonialism, neocolonialism, imperialism, white savior complex (we will talk about these last terms specifically in the next section) and others — and how they are woven into different systems in society. How might structural inequities and discrimination affect an individual’s, community’s or entire population’s health outcomes?

Structural inequities refers to the systematic disadvantage of one social group compared to other groups with whom they coexist that are deeply embedded in the fabric of society.

(National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2017)

The image of the tree below is a good representation of how the structural and social determinants of health are connected and affect the health outcomes of individuals, communities and populations.

- View the earth the tree is planted in as the structural determinants of health, which set the foundation for a society’s institutions and norms — such as government and laws, schools, the organization of cities and neighborhoods including the location of environmental pollution, voting districting, quality housing and access to healthcare.

- The earth feeds the roots of the tree, which are the social determinants of health. The quality and characteristics of the earth affect the quality and characteristics of the roots, or SDOH, which affect individuals’, communities’ and populations’ health.

- Think of the trunk and branches as a person, community or population and the fruit on the tree as their health outcomes. The health of the trunk and branches depend on the quality of the dirt and roots below. If the roots, trunk and branches are healthy the fruit produced by the tree will have a better chance of being healthy as well.

- Chances and ease of achieving health for individuals, communities and populations all depend on the positive and negative structural and social determinants of health that hold them up and facilitate access – or not – to factors which affect health (The Praxis Project, 2019).

To read more about SDOH models which explicitly call out structural determinants of health and their relationship to SDOH, as well as how to work towards health and social equity and justice, visit The Praxis Project website.

As we will learn in the next section in more detail, structural and social determinants of health are often rooted in long histories of social injustice: the deliberate racialization, marginalization, minoritization, oppression and disenfranchisement of certain populations. Historical events are contributors to the structural and, therefore, social determinants of health — and the disparities we are looking at this semester.

We will also see throughout the course that communities that have been systematically marginalized show resilience and resistance in the face of oppression. Indigenous, racially minoritized and grassroots community groups around the world are advocating for justice and working to reclaim and protect their lands, livelihoods and health from structural racism through improved social, economic and environmental conditions. While we recognize the massive economic, social, environmental and health inequities around the world, we also recognize the resistance and resilience of populations who are fighting everyday to claim their human right to health and well-being.

At the same time, we emphasize that no one should have to be resilient when they or their communities are marginalized, oppressed, silenced, discriminated against, experience violence or have their lands occupied and stolen from them. These acts should never happen in the first place and damages done should be righted through reparations, justice and Lands Back. Resilience should be recognized but not romanticized. We do not believe resilience should be the defining characteristic of any population — our common humanity should.

Through the experience of writing this resource we hope to open space for more conversation and exchange. As authors and educators we are learning as we go — and welcome any and all feedback or suggestions from students, colleagues and readers as to how we might improve this experience and conversation.

Bringing it together: relating SDOH to health outcomes

The relationship between the structural and SDOH and health outcomes for individuals, communities and populations is not just theoretical. As we learned in a previous section, the work of a type of public health professional called an epidemiologist is to study the causes, spread and patterns of disease. Epidemiologists use research — both statistics and verbal narratives — to understand the root causes of disease, how it spreads, who it affects and why. This type of work allows us to see the factual relationships between structural and SDOH and health outcomes.

Epidemiologists and other public health researchers use different frameworks and models to plan research to understand the root causes of health challenges. The social ecological model is one of those frameworks that we will reference throughout this course and that is one way of illustrating the different levels of the structural and SDOH.

The Social Ecological Model of Health Behaviors

This sub-section adapted from Aronica et al. (n.d.) with additions from Sallis et al (2008) and Skolnik (2021) where cited.

For a long time, Public and Global Health professionals focused on individual knowledge and attitudes as the main determinants of health behavior. Even today, many Public and Global Health interventions that aim to influence individuals to adopt evidence-based, positive health behaviors are founded on the assumption that individual behavior change requires education alone.

For example, under this assumption if a woman is not using a modern method of birth control, she just simply must not understand the benefits of birth control for her health or the health of her young children. Or, if an adolescent starts vaping they simply must not realize the short- and long-term risks that vaping could have on their health. The reality is, even if individuals receive information on the benefits and risks of different health behaviors, there are a number of other factors which influence and affect individual decisions around health behaviors. What about the influences of family and friends’ beliefs and behaviors? Maybe the woman who is not using birth control is forbidden by her husband to use it. Socio-economic factors which might affect an individual’s access to information? Influences of social media? Does the adolescent smoker see his friends posting pictures of vaping on social media and feel social pressure to act like them? Could there be language barriers? Information distrust? Cultural factors? Think about what influences your health behaviors. The list of potential influences goes on…

From the 1950s, professionals from across the social sciences began to recognize the different types and levels of influences on individual behaviors. They developed models and frameworks to better understand and represent the multi-level influences on human behavior, including health behavior (Salis et al., 2008). From the 1950s to today, different versions of these models have been created and adapted as our understanding of influences on health behaviors change. The social-ecological model is a general framework or perspective through which we understand influences on individual and population health behaviors and how to approach health behavior change.

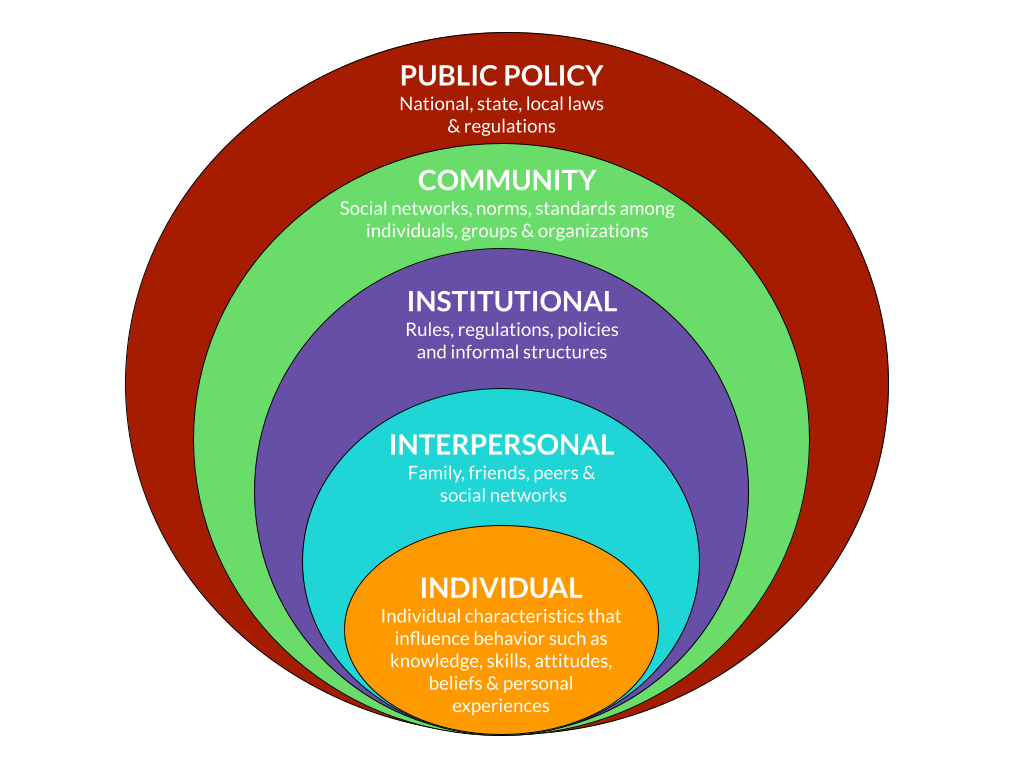

The Social-Ecological Model or Ecological Model takes into consideration the individual, and their affiliations to people, organizations, and their community at large to be effective. There are five stages to this model – Individual, Interpersonal, Organizational, Community, and Public Policy.

(Aronica et al., n.d.)

Two core principles of any ecological perspective on health and health behavior change are that:

- Multiple levels of factors influence health behaviors

- Influences interact across levels (Sallis et al., 2008).

The term ecology is derived from biological science and refers to the interrelations between organisms and their environments. Ecological models, as they have evolved in behavioral sciences and public health, focus on the nature of people’s transactions with their physical and sociocultural surroundings, that is, environments.

(Stokols,1992 in Sallis et al., 2008)

This social-ecological model (also referred to as the ecological model) has five levels:

- Individual

- Interpersonal

- Institutional

- Community

- Public Policy

(Adapted from Aronica et a.l, n.d., Murphy, E, 2005 and Skolnik, R 2021)

Different authors from different fields of social science or specialties within Public and Global Health might list the various levels in a different order, or might call the levels by slightly different names. The underlying concept of the model, however, remains the same.

Source: Adapted from Aronica et al., (n.d. ), Murphy, E. (2005) and Skolnik, R (2021)

| Level of the Socio-Ecological Model | Description of each Level of Influence |

| Individual | –> Individual characteristics that influence individual behavior including knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs, and personal, lived experiences –> Individual characteristics or identities such as age, gender, race or religion can also influence individual behavior especially if these are perceived of or treated a certain way in an individual’s socio-cultural context |

| Interpersonal | –>Primary groups surrounding an individual including family, friends, neighbors, co-workers and social media networks |

| Institutional | –> Formal and informal rules and regulations which guide or govern how an individual must behave within institutions –> Examples include schools, workplaces, government spaces, private businesses and others |

| Community | –> Networks, relationships, norms and standards (formal or informal) among individuals, groups and organizations –> Examples include networks, norms or standards in geographic neighborhoods or groups of people or organizations with which the individual identifies, among others |

| Public Policy | –> Local, state and federal policies and laws that regulate or support healthy actions and practices, or the SDOH which can affect an individual’s, community’s or population’s ability to achieve a high standard of health |

The social ecological model is a framework put in place in order to understand the multifaceted levels within a society and how individuals and the environment interact within a social system. Many designs of the model are made so that the different levels overlap, illustrating how one level of the model influences the next. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in order to prevent certain risk factors for poor health outcomes, it is necessary to take action at multiple levels of the model at the same time (CDC, 2018).

Now let’s look at how particular SDOH are related to health outcomes. We will use the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SDOH framework to guide us and explore the relationship between a SDOH from each of the five areas. As we do so, keep the social ecological model of health behavior and health outcomes.

→ Reflect on how lived realities at the different levels of the social ecological model might impact on each of the relationships described in the sections to follow.

→ To improve the health outcomes we describe in the sections below, what interventions could you imagine implementing at different levels of the social ecological model to improve individual and population health outcomes?

- Economic Stability

- Education Access and Quality

- Health Care Access and Quality

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

- Social and Community Context

Source: Healthy People 2030a, n.d.

Economic stability: Income, poverty and health

Being sick often costs money. Sometimes, a lot of money.

Even if you live in a country that provides healthcare for its citizens, you may not have many paid sick days from your place of employment. What if you work for yourself? Or earn money to feed your family by selling goods, food or services on the street everyday?

In many countries, such as the United States, if you do not have health insurance you must pay for the direct costs of health services yourself and these services can be incredibly expensive — even unaffordable for many people.

Direct costs or out of pocket expenditures refers to any money a person or household must pay themselves to receive health services including paying for insurance or co-pays, seeing medical providers, medical treatments or procedures, medications, hospital stays and other health-related services.

(Direct Costs, 2008)

Do not forget that the cost of accessing and receiving healthcare is often more than just the cost of health services themselves. How much will transportation cost? Will you lose wages or income if you have to take a day off from work to go to an appointment or recover from an operation? Do you need childcare or to stay in a hotel because you live far away from the health provider or health facility? Do you need to pay for meals out while caring for a family member in hospital? In many contexts around the world, the cost of hospitalization does not include food or regular nursing care for the patient. This responsibility for food and basic help in the hospital falls to a family member who must spend time and money caring for their loved one.

These types of costs are considered indirect costs of healthcare, but are just as important to consider as the direct costs of health services.

Indirect costs of healthcare include all costs associated with accessing or receiving health services aside from the cost of services themselves. These can include wages or opportunities lost because of the need to receive health services.

(Yousefi et al, 2014)

As you can tell, there are many reasons why access to financial resources (money!) is a significant SDOH. The direct and indirect costs of health services can be unattainable for families living in poverty. Costs of health services relative to an individual’s or a household’s income will also affect how quickly sick people seek out health services and the type and quality of services they are able to access. Higher income, however, is also associated with better access to other quality SDOH such as quality education, basic needs such as electricity, heat, clean water, sanitation and a healthy environment, safer housing and work conditions, better transportation and others.

Across key health outcomes, including life expectancy, infant and child mortality, rates of chronic disease and others, low socio-economic status and limited access to finances have negative effects on health. Generally, as financial resources increase we expect health outcomes to increase. This applies on the individual, household and country level.

Look at the graph below. What do you notice about life expectancy as a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) (a commonly used measure of a country’s wealth) increases? As a country’s wealth increases, what happens to life expectancy?

What relationship do you observe between World Bank Income Group and the Child (Under 5) Mortality Rates? With a higher income designation, do you notice an increase or decrease in the Under 5 Mortality Rate?

Data retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/ on August 12 2021

The data above should support the general trend that as a country’s wealth increases, health outcomes improve as well. There are, of course, many other factors (like the SDOH!) which impact individual health outcomes. But generally, increased generation of and access to financial resources at the national level leads to improvements in population health.

Now look at the graphs below. Does this relationship between wealth and health seem to continue within countries? How do the child mortality rates in poorer populations in each country compare to the child mortality rates of richer populations in each country?

Data retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/ on August 12 2021

As you can see, the relationship between access to financial resources and health outcomes can also be observed within countries. If we look at most health outcomes by wealth in most countries around the world, we would see the poorest populations within a country have worse health outcomes compared to the richest populations.

Education and health: a two way street

How does a person’s level of education affect their health outcomes?

Conversely, how does a person’s health status affect their educational attainment?

Look at the graphic below from the Center on Society and Health (2014). The relationships between health and education can flow in two directions.

While watching this video, think about how having a higher paying job as a result of higher education, for example, could lead to improved health outcomes (hint hint…remember the section above on the links between access to financial resources and health!)

For a more detailed summary of how higher education affects health outcomes and how health outcomes can affect education, you can review this document from the Center on Society and Health (optional, only if you want to learn more).

More education also often leads to increased health literacy which plays a significant role in a person’s ability to navigate health care systems and receive the care they, their children and their family members need.

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

CDC, 2021

Some more food for thought — the education of an individual does not just affect the health of that individual alone. For example, how do you think the education level of a mother could affect the health of her child? Or, how could the education level of a daughter or son affect the health care an elderly parent receives?

Research shows that maternal literacy and education have an impact on child health outcomes. More literate and educated mothers possess higher levels of health literacy, which means they are better able to obtain and process health information for themselves and their children, more able to advocate for their children in health care contexts and access the care their children need.

For example, a number of studies from countries around the world have found that maternal literacy and increased maternal education increase the chances that a child will be fully vaccinated (Forshaw et al, 2017).

Healthcare access and quality & Neighborhood and Built Environment: Location and health

Simply put, location matters.

Think about where you physically live — the location of your home, your neighborhood and your community — and how that location influences your health and ability to access healthcare. Do you live in an urban area? Are there doctors and hospitals close by? Do you live in a rural area? Can you walk anywhere, or do you need to drive far distances to access basic health services? What about accessing healthy food? Think back to the video clip we viewed earlier about access to affordable, healthy food in a Washington, DC neighborhood.

We can think about location and health on different levels. The country we live in, the community (city or town) we live in, even our neighborhood or street. As we move through this course, think about how an individual or population’s physical location is a determinant of their health — from exposure to different weather patterns including the increasing effects of climate change to access to food, places to exercise and health services — location can have an effect on all of these factors.

In this section, let’s focus specifically on how the determinants of health differ between urban and rural areas.

Globally, more and more people are migrating to urban areas in every country around the world. What are the effects of this urban migration on health, especially access to health care?

Generally, urban populations have easier access to a wider variety of quality health services than rural populations. Health services and health providers, especially health specialists that treat diseases like cancer or diabetes or perform complicated operations like heart surgery or orthopedic surgery, tend to be more concentrated in urban areas. For example, look at the number of primary care physicians and psychiatrists in the state of Illinois per 100,000 people in large urban counties versus rural counties in 2018 (Rural health Summit Planning Committee, 2018).

The difference is huge!

Source: Rural Health Summit Planning Committee, 2018

These same disparities tend to exist in countries around the world so that rural populations have a more difficult time accessing the health care they need when they need it. With fewer physicians, longer distances to travel to health services especially for specialist care, a general lack of public transportation and often less access to higher paying jobs, rural health populations generally have poorer health outcomes than their urban counterparts.

Social and Community Context: Social cohesion and health

When we talk about a person’s ‘social and community context’, we are talking about their ‘relationships and interactions with family, friends, co-workers, and community members’ (Healthy People 2030a, n.d.).

Having the support of family members, friends, co-workers and neighbors can have a positive impact on a person’s mental and physical health in a number of ways. Think of the positive effects on both mental and physical health if you are able to call a friend to help you get to an important doctor’s appointment, invite a friend over for dinner if you live alone or greet your neighbors as you walk to the bus stop every morning. These positive relationships with supportive people are examples of social cohesion.

Social cohesion refers to the strength of relationships and the sense of solidarity among members of a community.

(Healthy People 2030b, n.d.)

Watch this video from a health survey in the state of Arizona to learn more about research that has shown that social cohesion has a significant and positive impact on health outcomes. As you watch this video, remember that any community, regardless of socio-economic status, can form strong social cohesion for positive effects on health.

The country of Guyana in South America has recognized the importance of social cohesion to community and economic development so much that they established a governmental Department of Social Cohesion!

A lack of social cohesion in an individual’s life or within a community is often related to structural determinants of health. For example, people and communities who are systematically marginalized and discriminated against based on factors such as race, disability, gender identity, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, immigration and refugee status, and incarceration can experience profound, negative impacts on their health.

If a person feels they do not have the support of others in their lives, that they are not a part of a community, or if their interactions with others on a day to day basis feel stressful or even dangerous, this can have an impact not only on their mental health but their physical health as well. We will explore the relationship between discrimination, such as racism and sexism, and physical and mental health outcomes in upcoming sections of the course.

Summary

That wraps up our introductory conversation about the determinants of health. We know there is a lot of information and new perspectives to take in. One way of making the social and structural determinants of health ‘real’ is to think of these concepts when you walk out of your front door in the morning. Look around. Does the world look different if you see your daily commute, your morning walk, your route to the grocery store or doctor or library as contributing to your health and well-being? Which of your neighbors might have more — or less — difficulty accessing those services in your area? We are living the SDOH and structural determinants of health everyday, and while infectious agents, genes, sex, age and lifestyle choices do play a role in health status the social and structural determinants of health will inarguably affect the path to those outcomes in very different ways for different populations in communities and countries around the world.

For the rest of this course we will look at how the different determinants of health — biological, social, structural, historical and more — affect health access and outcomes for different populations within and between countries around the world.

Supplementary Resources

Education and health

Center on Society and Health: Why Education Matters to Health

https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/media/society-health/pdf/test-folder/CSH-EHI-Issue-Brief-2.pdf

Financial resources and health

Location and health

https://www.uniteforsight.org/global-health-university/urban-rural-health

Social Determinants, Health Equity & Health Disparities

Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity

Global Economic Inequality (more detailed/extensive reading) from Our World in Data

Covid-19 pandemic and the social determinants of health

References

- Aronica, K., Crawford, E., Licherdell, E., & Onoh, J. (n.d.). Social Ecological Model. Models and Mechanisms of Public Health. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-buffalo-environmentalhealth/.

- Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, Weinstein, J. (Eds.). (2017, Jan 11). Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. National Academies Press (US);. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425848/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, January 31). Health disparities. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/disparities/index.htm.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a, Dec 18). Adolescent and School Health: Terminology. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/terminology/sexual-and-gender-identity-terms.htm

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b, May 13). Mission, Role and Pledge. https://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/mission.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 9). Social determinants of health, health equity, and vision loss. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/determinants/index.html

- Center on Society and Health. (2014). Why Education Matters to Health: Exploring the Causes. Virginia Commonwealth University. https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/media/society-health/pdf/test-folder/CSH-EHI-Issue-Brief-2.pdf

- Committee on Indigenous Health. (1999) Report of the International Consultation on the Health of Indigenous Peoples. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69464/WHO_HSD_00.1_eng.pdf

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. (1991). Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Institute for Futures Studies.

- Forshaw, J., Gerver, S. M., Gill, M., Cooper, E., Manikam, L., & Ward, H. (2017). The global effect of maternal education on complete childhood vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2890-y

- Health Equity Institute (2016, July 12). What is Health Equity? [VIDEO]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HA5_1FMF-uo

- Healthy People 2030a. (n.d.). Social and Community Context. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/social-and-community-context)

- Healthy People 2030b. (n.d.). Social Determinants of Health. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

- Henry, R., Lavallee, A., Van Styvendale, N., & Innes, R. (Eds.). (2018). Global Indigenous Health: Reconciling the Past, Engaging the Present, Animating the Future.. TUCSON: University of Arizona Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv513dtj

- Illinois Department of Public Health. (n.d.). Understanding Social Determinants of Health.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2002. A, Models of Health Determinants. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221240/

- Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Health Policy Institute. (2012). Place Matters for Health in Cook County: Ensuring Opportunities for Good Health for All. Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. Washington, DC.

- Kirch, W. (Ed.). (2008). Direct costs. Encyclopedia of Public Health, 267–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_799

- Murphy, E. (2005). Promoting healthy behavior. Health bulletin 2. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

https://u.demog.berkeley.edu/~jrw/Biblio/Eprints/PRB/files/PromotingHealthyBehavior_Eng.pdf

- The Praxis Project. (2019). Social Determinants of Health. https://www.thepraxisproject.org/social-determinants-of-health

- Sallis, J., Owen, N., and Fisher, E. (2008). Chapter 20: Ecological Models of Health Behavior in AGlanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (Eds.). (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Schnecker, L. (2019 June 6). Chicago’s lifespan gap: Streeterville residents live to 90. Englewood residents die at 60. Study finds it’s the largest divide in the U.S. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-chicago-has-largest-life-expectancy-gap-between-neighborhoods-20190605-story.html

- Skolnik, R (2021). Global Health 101. Jones and Barlett Learning, Burlington, MA.

- World Health Organization (n.d.) Health impact assessment, Glossary of terms used. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/glossary-of-terms-used-for-health-impact-assessment-hia

- Yousefi, M., Assari Arani, A., Sahabi, B., Kazemnejad, A., & Fazaeli, S. (2014). Household Health Costs: Direct, Indirect and Intangible. Iranian journal of public health, 43(2), 202–209.