2. Key Concepts

- Race

- Racism

- Ethnicity

- Structural determinants of health

- Structural/ institutional/ systemic racism

- Direct violence

- Structural violence

- Cultural violence

- Generational / Intergenerational / Historical trauma

- Cultural genocide

3. Prelim Engagement

Trigger warning: The following section discusses concepts and experiences some individuals may find triggering and upsetting, including experiences of racism, discrimination and intergenerational trauma.

1. In this section we will focus on racism as a determinant of health outcomes. We will use specific examples of health disparities between Black and white Americans in the United States and Indigenous people and settler Canadians in Canada to illustrate how and why racism --- both in the present and from the past --- is a significant determinant of health and cause of health disparities.

As you move through this section of reading and content, think back to our exploration of different levels of violence as illustrated in the book Mountains Beyond Mountains by Tracy Kidder. Ask yourself how was and is racism manifested in the past and in the present as direct, structural and cultural violence in different contexts around the world?

2. As you work through this section, also think back to the different levels of determinants of health we continue to explore in this course. Racism can be understood as both a historical and structural determinant of health. As we also now know, historical and structural determinants of health impact social determinants of health within countries and on a global scale. However, did you also know that experiencing racism has proven direct effects on health outcomes including non-communicable conditions such as blood pressure? Combined with the stresses of disparities resulting from inequitable historical, structural and social determinants of health, we now know that the repeated and prolonged experience of racism adds up over time. The following video clip and short article explore this proven link between experiencing racism and health outcomes in more detail, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read this article: Who's Hit Hardest by COVID-19? Why Obesity, Stress and Race All Matter

3. If a mother, father or community as a whole experience a traumatic event or ongoing traumatic events --- such as war, genocide, violence or racism --- will the next generation feel any effects of those experiences? The answer is in many cases yes. While individuals and communities can be incredibly resilient during and after traumatic events, the experiences and effects of trauma are often felt and passed down to subsequent generations often in subtle but significant ways. We will explore the effects of what is referred to as generational, intergenerational and historical trauma in-depth through the experiences of Indigenous peoples of Canada and their experiences in residential schools.

Author Joanna Rice writes:

“Beginning in the 1880s, Aboriginal children across Canada were removed, often forcibly, from their homes and placed in Indian Residential Schools. At the schools, students were forbidden to speak Native languages and practice their culture. Testimony from surviving former students presents overwhelming evidence of widespread neglect, starvation, extensive physical and sexual abuse, and many student deaths related to these crimes. As is so often the case with state-inflicted mass atrocities, records indicating accurate rates of abuse and death at residential schools do not exist or were destroyed…[E]stimates suggest that sexual abuse rates were as high as 75 percent in some schools, and rates of physical harms were higher still. …

[S]earching for a precise number for rates of abuse at the schools is beside the point. The larger crime is that these schools were designed and operated by the church and state with the purpose of destroying Native cultures and communities in every corner of Canada” (2011).

We will explore the history, violence and intergenerational effects of residential schools and other policies against Indigenous people in Canada in detail in the section to follow. The practices, abuse and violence in residential schools in Canada described by Rice (2011) above were also reported in residential schools in Australia and the United States. As you learn more about residential schools, think about our discussions related to colonialism and health.

The video clips below give definitions of intergenerational trauma and examples from residential schools in Australia and Canada. It is important to note that residential schools were also established in the United States to ‘assimilate’ Native American children from their indigenous culture --- language, religious beliefs, cultural practices and more --- to white culture.

Trigger warning: The following section discusses concepts and experiences some individuals may find triggering and upsetting, including experiences of racism, discrimination and intergenerational trauma.

Start with the basics: defining race and ethnicity

We hear and discuss the terms and experiences of ‘race’ and ‘racism’ frequently in the media, in our classrooms, professionally and especially in the fields of Public and Global Health.

But if you were asked to actually define race, what would you say?

Is race biological, related to genetics?

Or, is it a social construct — rooted in historical actions meant to justify divisions, discrimination and inequities?

If you said ‘social construct’ — you are correct.

We also often hear the term ethnicity mentioned next to or interchangeably with race.

Are these concepts the same?

The answer is — not necessarily.

Race is a social grouping of people who have similar physical or social characteristics that are generally considered by society as forming a distinct group.

Race is socially constructed…race is not an intrinsic part of a human being…but, rather, an identity created using symbols to establish meaning in a culture or society.

Race is partially characterized by physical similarities such as skin color, facial features or hair texture…human beings create categories of race based on physical characteristics rather than the physical characteristics having intrinsic biological meaning.

Race is partially characterized by general social similarities such as shared history, speech patterns or traditions.

…Race is not an inherent biological grouping, so racial categories emerge from historical processes and often gain legitimacy in society through political action.

(Bold added for emphasis Barnshaw, J. 2008 in Schaefer, R)

Sometimes this definition can be confusing — we are saying that race is not associated with genetics, but is associated with biological characteristics such as skin color, facial features and hair type. But we are also saying that most importantly race is a social construct. Racial categories, based on physical/biological features such as skin color, facial features and hair type, were created by humans throughout history.

These racial categories have often been used to justify divisions between groups, unequal power dynamics and violence — and not just in the distant past. Slavery, the Holocaust, neo-colonial policies, the Rwanda genocide and contemporary examples of direct and institutional or systemic racism are all examples of how socially constructed racial categories have been used to justify marginalization, oppression and violence by certain groups against certain groups.

A person or group of people’s ethnicity is not necessarily the same as their race, though individuals may choose to identify their race and ethnicity as the same.

Ethnicity depends on cultural and social factors such as family origin, language, diet and religion to classify humans. Your ethnicity is the group you belong to, or are perceived to belong to, in the light of such factors.

(Bhopal, 2016)

Watch the video clip below for a comprehensive discussion and definition of race and ethnicity.

Remember moving forward that ethnicity can also be used as a means to discriminate against particular groups. Certain beliefs and cultural practices can also come from ethnicity and ethnic identity. Therefore, ethnicity can also be considered a structural and/or social determinant of health.

Race or racism as a determinant of health?

Let’s also remember to correctly distinguish race from racism. While race refers to socially constructed categories and we see health inequities between races within and between countries, race itself is not a social determinant of health.

Racism, however, is.

The fact that an individual is born with black or white skin is not, alone, a determinant of health. What makes race a determinant of health are the histories and systems of oppression, marginalization and systemic racism which exist within certain contexts that make having black or white skin a determinant of health.

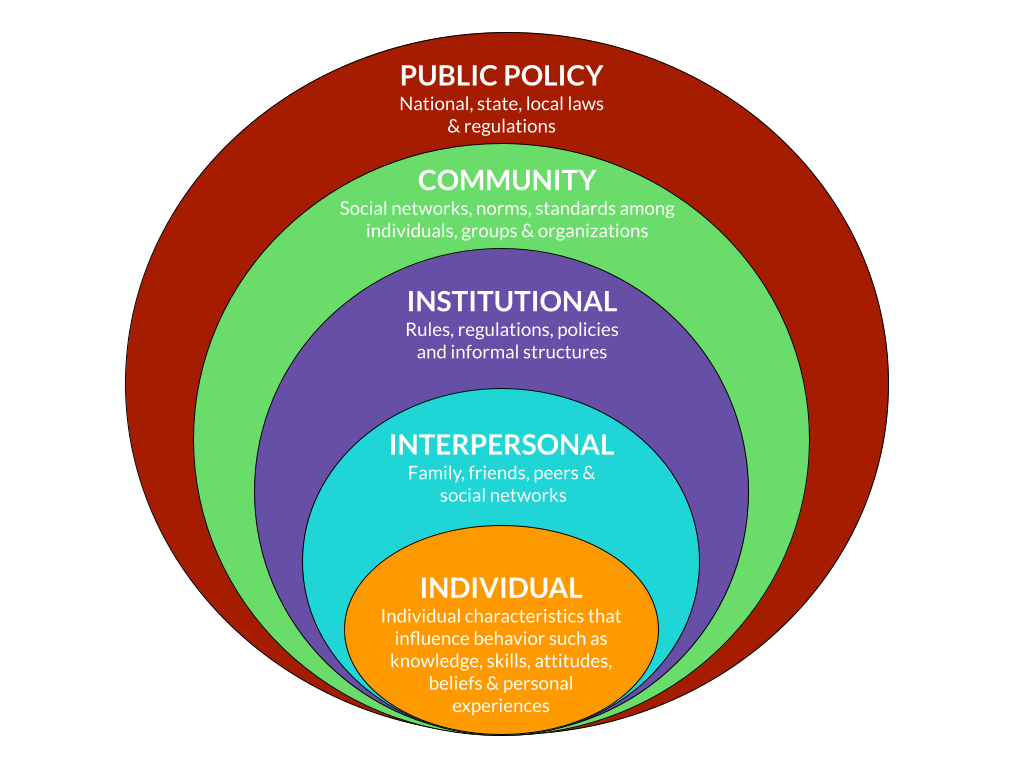

Let’s once again think back to the images we have used to understand the structural and social determinants of health, and the different social and systemic levels on which these determinants can be located.

Consider racism at the roots, feeding the systems that influence, shape and distribute the social determinants of health. For those individuals and communities which have been systematically racialized and marginalized within systems that are founded on racism, it is easy to see how racism becomes a structural and, indirectly, social determinant of health.

If racist systems did not exist and resources and opportunities were truly distributed equally between all groups of people, race would not act as a determinant of health outcomes.

While race is a social category based on physical attributes, racism is an organized system based on an ideology of inferitority that categorizes, ranks and differentially allocates desirable society resources [and opportunities] to socially defined ‘races.’

(Smedley et al, 2010)

It is important to recognize this distinction between race and racism. Race in and of itself is not a determinant of health; being born a certain race in a racist system, however, is.

There are different ways of understanding where and how racism is present and experienced by individuals who identify as or are perceived as belonging to a particular race.

Racism can happen at the interpersonal level or at the systemic level.

Racism at the interpersonal level is the most recognized form of racism. Also known as relational or individual racism, it happens when individuals experience discriminatory behaviour from other people. These behaviours are based on the long-standing ideology of racism (i.e. racial superiority). Interpersonal racism is expressed explicitly or implicitly through prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination.

(Canadian Medical Association and the Government of the Northwest Territories, 2021)

Also referred to as institutional racism, systemic racism occurs when mainstream institutions and organizations formalize and condone long standing racist ideologies into policies, practices and norms. This reinforces racial hierarchies that inherently privilege the ideas and needs of the dominant white population while disadvantaging non-white racial groups. Systemic racism permits interpersonal racism in the workplace through direct racist policies or the absence of policy and accountability measures to address it.

(Canadian Medical Association and the Government of the Northwest Territories, 2021)

Linking race to health outcomes

For centuries, medical providers, researchers, public health professionals, politicians and historians believed, assumed and taught that race was genetic. Supposed ‘genetic differences’ between races were used to explain why certain races were more susceptible or more immune to certain diseases.

Let’s take the COVID-19 pandemic in the city of Chicago as an example. As of June 2020, Black Chicagoans were dying from COVID-19 at a rate more than 2.5 times higher than white Chicagoans (Colvin and Murphy, 2020).

Are Black Americans genetically more susceptible to COVID-19 than white Americans?

Well, as we established above, race does not stem from genes. Racial categories are based on physical attributes — and those same racial categories were socially constructed and applied by humans throughout history.

By now, when you see an unequal health indicator like mortality rates from COVID-19 by race, your Public Health red lights should be flashing. Is this simply an inequality or an inequity? Inequity is right — avoidable, unfair and unjust. Your Public Health mind should also kick into gear and consider what historical, structural and social determinants of health might be responsible for such drastic inequities in mortality rates from COVID-19 by race in Chicago, especially at the beginning of the pandemic when health systems were overwhelmed and those who could were working from home with little contact with other people.

As anthropologist William Dressler has pointed out, “So many medical conditions are differentially distributed to African Americans – heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, low birth weight babies – are we to believe that Black people were so evolutionarily unlucky that they got all the genes that predisposed them to every malady?” (Smedley et al, 2010)

Across the United States and around the world, racial and ethnic minority populations experience higher rates of poor health and disease in a range of health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, obesity, asthma, and heart disease, when compared to their White counterparts. The life expectancy among Black/African Americans is four years lower than that of White Americans (CDC, 2021b).

Now that you have a bit more context, watch this video clip that details why and how racism has been declared a Public Health crisis in the United States by some cities and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REQUIRED ARTICLE: Who’s Hit Hardest by COVID-19? Why Obesity, Stress and Race All Matter

The following excerpts from an article on race, inequality and health inequities by Smedley and colleagues (2010) explores the intersection of determinants of health further, disproving the myth that racial differences in health outcomes can be attributed to genes alone.

Excerpts from Race, Racial Inequality and Health Inequities: Separating Myth from Fact

by Brian Smedley, Michael Jeffries, Larry Adelman and Jean Cheng

Note: This paper is from 2010 so some statistics may have changed slightly.

Nearly eight million television viewers tune in to Oprah each day. So when Oprah Winfrey weighs in on a complex, controversial issue such as racial health differences her words carry weight – even when she’s wrong.

During a May 2007 Oprah show, “America’s Doctor” Mehmet Oz asked Oprah, “Do you know why African Americans have high blood pressure?” Oprah promptly replied that Africans who survived the slave trade’s Middle Passage “were those who could hold more salt in their bodies.” To which Oz exclaimed, “That’s perfect!”

In other words, according to Dr. Oz and Oprah, African Americans today are afflicted by hypertension at nearly twice the rate of whites because of the genes passed on by their ancestors, genes that favored salt retention and which in turn can cause high blood pressure.

Sounds reasonable. But the so-called “salt retention slavery hypothesis” has long been discredited.

In fact, a growing body of scientific evidence points to social conditions – not genes – as key not just to differences in hypertension rates but to other large and persistent health differences between American racial and ethnic groups.

As anthropologist William Dressler has pointed out, “So many medical conditions are differentially distributed to African Americans – heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, low birth weight babies – are we to believe that Black people were so evolutionarily unlucky that they got all the genes that predisposed them to every malady?”

This fact sheet briefly explores some of the common myths and misconceptions about

race and health, and why a fruitful search for the underlying causes of different racial

health outcomes must necessarily begin not inside our bodies but outside, in the larger

social, economic and built environments in which we are born, work and live.

What Are Racial Differences in Health?

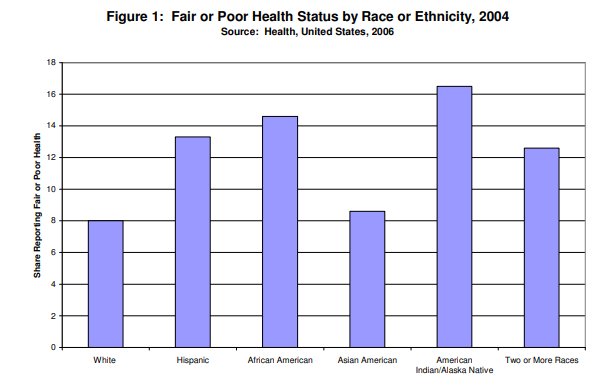

Oprah was right on one point: there are still large racial and ethnic inequities in health, and not just hypertension. In general, African Americans, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders live shorter lives and have poorer health outcomes – e.g., worse life expectancy, infant mortality, coronary artery disease, diabetes, stroke and HIV/AIDS – than whites and Asian Americans.

New immigrants have better overall health than their peers at comparable levels of income and education, but their health tends to get worse the longer they live here. By the second generation they too lag whites by many indicators. And while Asian Americans as a whole also fare better than whites, that’s not true for some Asian American sub-populations.

Health inequities between African Americans and whites have been studied the most. According to the Centers for Disease Control, African American men die on average 5.1 years sooner than white men (69.6 vs. 75.7 years) while African American women die 4.3 year sooner than white women (76.5 vs. 80.8 years) and they face higher rates of illness and mortality.

The numbers are staggering. According to a recent study by former Surgeon General Dr.

David Satcher and Dr. Adelwale Troutman, 880,000 “excess” deaths could have been

averted between 1991 and 2000 had African Americans’ health matched that of whites.

That’s the equivalent of a Boeing 767 shot out of the sky and killing everyone on board every day, 365 days a year, points out David Williams of Harvard’s School of Public Health. And they are all black.

When asked about their health, minorities of all groups are more likely than whites to report being in fair or poor health (Figure 1). American Indians are more than twice as likely as whites to report being in fair or poor health than whites; African Americans and Latinos also have far higher rates of fair or poor health than whites.

…

What is Race?

To track the underlying causes of our racial health disparities, we must first raise a question so basic it’s rarely asked: what is race? Sadly, the Oprah-Oz exchange likely reinforced many viewers’ assumptions that humans come bundled into three or four biologically distinct groups called “races”–and that group differences in health outcomes can be attributed not to their different lived experiences but to some inborn set of biological differences.

However, most scientists today agree that human biological diversity does not map along what we conventionally think of as racial lines. The approximately 30,000 genes in our DNA are inherited independently, one from another.

To take three examples:

Skin color patterns one way. Sub-Saharan Africans, Dravidians and Tamils in South Asia, Aborigines in Australia and Melanesians all share the trait of dark skin yet are conventionally placed in different “races.”

Blood groups cluster differently. For example, the populations of two countries on opposite sides of the globe, Lithuania and Papua New Guinea, have virtually the same proportions of A, B and O blood. Yet they too have conventionally been assigned different “races.”

The lactase enzyme needed to digest milk maps yet a third way. Lactase is common among northern and central Europeans, Arabians, many east Africans and the Fulani of west Africa, and north Indians, while rare among Southern Europeans, most West African, East Asians, and Native Americans.

While some gene variants (called ‘alleles’ by geneticists) are more common in some populations than another, there are no characteristics, no traits, not a single gene that are found in all members of one population yet absent in others. Skin color really is only skin deep. (There are ways to deduce the possible birthplace of some–though far from all!–of

an individual’s ancestors using DNA markers but that should not be confused with what we call race).

Genetic explanations for racial and ethnic health differences are also undermined by empirical studies.

For example, African Americans, as Oprah pointed out, do suffer the highest hypertension rates of any U.S. population. But Richard Cooper and colleagues found that western Africa, from where many African Americans descended, has among the world’s lowest hypertension rates, one third that of African Americans. Meanwhile they found some of the world’s highest hypertension rates among white European populations, much higher than both white Americans and African Americans. If predisposition to hypertension were truly the result of ‘racial’ genes, all recent African-origin peoples would share similar rates of illness, as would the European-origin populations.

Other research bears out Cooper’s finding. Low birth weight, for example, is a large risk factor for infant mortality and health problems through the life course and disproportionately affects African Americans. Richard David and James Collins found that African American newborns weigh on average a half-pound less than white Americans. But the babies of African immigrants to the U.S. weighed the same as the white babies, even after adjusting for factors such as education level.

But David and Collins also discovered something else: The daughters of African immigrants delivered babies that weigh on average a half-pound less than the white American babies. In other words, they have become “African American.”

“So within one generation, women of African descent are doing poorly,” Collins said in the documentary Unnatural Causes. “This to us really suggests that something is driving this that’s related to the social milieu that African American women live in throughout their entire life.”

Genes certainly play a role on an individual level in disease susceptibility. But those genes don’t neatly divide up along ‘racial’ lines. The impact of race on disease, explains sociologist Troy Duster, is not biological in origin but biological in effect.

Searching for the source of disease difference inside the body diverts our attention from addressing those sources of disease difference that lurk outside the body.

Racism—A Cause of Disease as Surely as Germs and Viruses

So how does race get under the skin and influence our physiology if it isn’t biological?

The lived experience of race, or to be more blunt, racism, influences how people are treated, what resources and jobs are available to them, where they are likely to live, how they perceive the world, what environmental exposures they face, and what chances they have to reach their full potential. These, in turn, promote or constrain opportunities for health.

Racism operates both upstream of class and independently of class. Upstream, educational, housing and wealth-accumulating opportunities have been shaped by a long history of racism that confers economic advantage to some groups while disadvantaging others. For example, studies of hiring have consistently found that employers prefer white candidates over African American ones, even when their qualifications are identical. In fact, one study even found that fictitious white applicants with a felony record were preferred over Black applicants with no criminal history. And lower socioeconomic status translates into poorer health.

But racism also operates independently of class, helping explain why racial health inequities persist even after controlling for socio-economic status. Segregation and social isolation, the cumulative impact of everyday discrimination on chronic stress levels, the degree of hope and optimism people have, the location of doctors and hospitals, and differential access to and treatment by the health care system all place an extra burden on subordinated racial and ethnic groups.

Structural Racism and Residential Segregation as Vectors of Disease

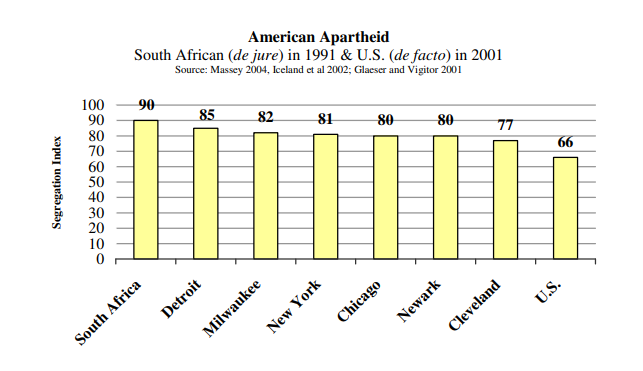

Incredibly, 45 years after the Civil Rights Act, one of the strongest forces shaping opportunity–and health– is still segregation, particularly for poor African Americans and Latinos. Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton call segregation “the key structural factor for the perpetuation of black poverty in the U.S.”

One measure of residential segregation is called the “Dissimilarity Index.” It’s the percentage of a group that would have to move in order for that group to be evenly distributed across a metropolitan area. African Americans in New York have a Dissimilarity Index of 81, meaning that 81% of New York’s black population would have to move in order to achieve an equal integration rate. How segregated is New York?

South Africa’s Dissimilarity Index under apartheid in 1991 was 90. Figure Four compares African American segregation in several American cities, South Africa and the U.S. as a whole.

Segregation didn’t just materialize “naturally.” David Williams reminds us that segregation was “imposed by legislation, supported by business and banks, enshrined in government housing policies, enforced by the judicial system and vigilant neighborhood organizations, and legitimized by the ideology of white supremacy.” Today segregation is maintained by economic inequality, exclusionary real estate practices, unequal spending on schools, and fear.

Residential segregation adversely affects population health directly and indirectly.

Social Exclusion. Racial segregation concentrates poverty and excludes and isolates communities of color from the mainstream resources needed for success. African Americans are more likely to reside in poorer neighborhoods than whites of similar economic status. For example, poor African Americans were 7.3 times as likely to live in high poverty neighborhoods as poor white Americans in 2000; Latinos 5.7 times as likely. Those rates have doubled since 1960.

Economic Opportunity. Segregation also restricts socio-economic opportunity by channeling non-whites into neighborhoods with poorer public schools, fewer employment opportunities, and smaller returns on real estate. These limits on economic opportunity have a strong, indirect impact on health given the strong and well-documented tie between wealth and health.

Healthy Choices. The behavioral choices people make are constrained by the choices people have. It is more difficult to make healthy choices in segregated neighborhoods. One study revealed that black Americans are five times less likely to live in census tracts with supermarkets than white Americans. Nationally, 50% of black neighborhoods lack access to a full service grocery story or supermarket. It’s more challenging to eat right in neighborhoods where fast-food joints, liquor stores and convenience stores proliferate while supermarkets and other sources of affordable, nutritious food are hard to find. The fruit and vegetable intake of Black residents increased an average of 32% for each supermarket in their census tract.

Black and Latino neighborhoods also have fewer parks and green spaces than white neighborhoods, and fewer safe places to walk, jog, bike or play, including fewer gyms, recreational centers and swimming pools.

Their neighborhoods are less likely to be walk-able (homes near stores and jobs) and more likely to have streets that are not safe after dark. Cautious parents in poor neighborhoods keep their children indoors after school – where they are more likely to watch TV, play video games and eat – rather than allow them out to play on unsafe streets.

These characteristics of place all contribute to higher obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular

disease rates among people of color, especially poor people of color.

Environmental Hazards – Dozens of empirical studies over the past 40 years have determined that low-income communities and communities of color are more likely to be exposed to environmental hazards. For example, 56% of residents in neighborhoods with commercial hazardous waste facilities are people of color even though they comprise less than 30% of our population.

Housing – Crowded, substandard housing, elevated noise levels, decreased ability to regulate temperature and humidity, and exposure to lead paint and allergens such as mold and dust mites are all more common in poor, segregated communities, as are asthma rates, sleep disorders and lead toxicity.

Schools – Education correlates very strongly with earning opportunities and with health, even life expectancy. Minority students, however, remain highly concentrated in majority-minority schools, despite five decades of effort since the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision to desegregate them. Not only do poor and minority school districts receive less funding, have larger class sizes, worse physical infrastructure and more non-credentialed teachers than white districts, but fifty years after the Brown decision, the re-segregation of our schools continues throughout the country. According to a 2007 Civil Rights Project study, “The children in United States’ schools are much poorer than they were decades ago and more separated in highly unequal schools. Black and Latino segregation is usually double segregation, both from whites and from middle class students.”

Crime – Residents of segregated communities are exposed to more crime and violence as a result of concentrated poverty and the collective inability to exert social controls.

Violence affects health directly, of course, by increasing the risk for injury and death. But as Robert Prentiss, director of the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative, points out in UNNATURAL CAUSES, the specter of community violence has ripple effects that contribute to poor health “by changing the way people live in certain neighborhoods: the ability of people to go out, to go shopping, to live a normal life, and also indirectly by increasing chronic stress.”

Incarceration – African Americans, Latinos, and American Indians are disproportionately imprisoned and penalized by the criminal justice system.

Communities with high arrest and imprisonment rates do not develop the social bonds and networks needed to maintain order. Black people are currently incarcerated at a rate 5.6 times that of whites, while the Hispanic rate of incarceration is 1.8 times that of whites. One out of every 14 Black children has at least one parent in prison.31 Families torn apart by incarceration have fewer human and financial resources for childrearing, and children in disadvantaged neighborhoods have fewer stewards for healthy socialization.

The ‘Poverty Tax’ – According to a Brookings Institution study, not only do poor neighborhoods have fewer parks, fewer supermarkets, worse schools, more environmental hazards, higher crime and neglected public spaces, residents pay more for the exact same consumer products than those in higher income neighborhoods– more for auto loans, furniture, appliances, bank fees, and even groceries. And homeowners get less return on their property investments. Sociologists call this “the poverty tax.” The “tax,” adding up to hundreds, even thousands of dollars, further impoverishes those who are already poor.

Racial Discrimination, Chronic Stress and Disease

Structural racism and segregation aren’t the only barriers to health and well-being faced by people of color. In addition to how discrimination limits economic opportunity, there is increasing evidence that encounters with prejudice take a direct toll on the body. In fact, more than 100 studies now link racial discrimination to physical health.

In one study, Black women who reported they had been victims of racial discrimination were 31% more likely to develop breast cancer than those who did not. Another study showed that Black women who identified racism as a source of stress in their lives had more plaque in their carotid arteries. Similarly, studies have tied experiences of discrimination with higher blood pressure levels and more frequent diagnoses of hypertension.

Experiences of racial discrimination are also associated with poor health among Asian Americans. Researchers who conducted a recent national survey with over 2,000 participants found that everyday discrimination was associated with a variety of health conditions, including chronic cardiovascular, respiratory, and pain-related health issues. Filipinos reported the highest levels of discrimination, followed by Chinese Americans and Vietnamese Americans.

New research suggests that racial discrimination may be damaging because it triggers the

stress response–over and over again. When we perceive a threat, or find ourselves in a situation that is difficult to manage and control, our body’s alarm bells go off. The brain goes on alert and releases cortisol and other stress hormones that trigger a physiological cascade: our senses are heightened, blood pressure and heart rate increase, glucose levels rise, our immune system is primed, all to help us hit harder, or run faster. It’s the classic “fight or flight” response taught in high school biology.

When the threat passes, our body returns to its normal state. But if stress is chronic, constant, unremitting, even at a low level, the body doesn’t return to normal. The body’s stress responses remain turned out, wearing on the body over time. Chronic stress has been found to increase risk for coronary artery disease, stroke, cognitive impairment, substance abuse, anxiety, depression and mood disorders, even increased aging and cancer.

Camara Jones, MD, of the federal Centers for Disease Control, likens it to “gunning the engine of a car, without ever letting up. Just wearing it out, wearing it out without rest. And I think that the stresses of everyday racism are doing that.”

Such exposures to discrimination seem to impose an added stress burden onto peoples of color in addition to those already associated with their lower socio-economic status. In other words, they get a double dose.

It is also well-known that exposures to chronic stress can further threaten health as a result of maladaptive coping behaviors such as eating, smoking, drinking, drug-taking, even violence.

Young children are especially vulnerable to stress. Early exposure to “toxic stress” can even change the hard wiring of the brain. According to Harvard’s Center for the Developing Child, poverty, racism, social exclusion, violence, physical deprivation and failure at school are among the factors that undercut the brain’s ability to construct circuits that build “resilience.” Instead, these children are primed to be highly reactive and extra-sensitive to stressors throughout their lives. The consequences of these childhood exposures can even carry over to the next generation, with the pregnant mother’s stress hormones affecting fetal development in the womb.

(Smedley et al, 2010)

Link to full article and references here: https://unnaturalcauses.org/assets/uploads/file/Race_Racial_Inequality_Health.pdf

‘Can trauma be inherited?’: Racism, intergenerational trauma and health

If a mother, father or community as a whole experience a traumatic event or ongoing traumatic events — such as war, genocide, violence or racism — will the next generation feel any effects of those experiences?

The answer is in many cases yes.

While individuals and communities can be incredibly resilient during and after traumatic events, the experiences and effects of trauma are often felt and passed down to subsequent generations often in subtle but significant ways. This is called intergenerational trauma, also sometimes referred to as generational trauma or historical trauma.

Intergenerational trauma is historic and contemporary trauma that has compounded over time and been passed from one generation to the next. The negative cumulative effects can impact individuals, families, communities and entire populations, resulting in a legacy of physical, psychological and economic disparities that persist across generations.

(Canadian Medical Association and Government of the Northwest Territories, 2021)

You should be able to think of many examples for potential intergenerational trauma that we have discussed throughout this course.

Think of the histories of violence — direct, structural and cultural — we have read about in Haiti and Rwanda in the book Mountains Beyond Mountains; colonial histories of oppression, exploitation and violence; the long-lasting effects of unethical medical experiments such as experiments carried out by Nazis during World War II against Jewish people, people identifying as LGBTQ and other ethnic minorities; the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, among others.

The Canadian Medical Association states that, “For Indigenous peoples, the historical trauma includes trauma created as a result of the imposition of assimilative policies and laws aimed at attempted cultural genocide and that continues to be built upon by contemporary forms of colonialism and discrimination (2021).”

Cultural genocide

As a legal concept in international law, cultural genocide was devised as a sub-category, or aspect, of genocide – the attempt to systemically and wilfully destroy a group – alongside physical genocide and biological genocide. It denoted the destruction of both tangible (such as places of worship) as well as intangible (such as language) cultural structures (Bilsky and Klagsbrun, 2018).

Cultural genocide is the systematic destruction of traditions, values, language, and other elements that make one group of people distinct from another (Novic, 2016).

The following videos define and explore the concept of intergenerational (or generational) trauma generally, including the fact that trauma can be passed on biologically from one generation to the next. Experiences of violence including abuse, war or genocide, emotional abuse, separation from parents or family as a child, or cultural genocide are all potential triggers and causes of intergenerational trauma and, subsequently, poor health outcomes.

It is highly recommended that you watch both of the following video clips.

Understanding racism and intergenerational trauma as determinants of health

As described in the Prelim Engagement section, residential schools were established beginning in the mid to late 1800s in Australia, Canada and the United States. These schools had the sole purpose of ‘assimilating’ Indigenous children into members of the white, settler cultures in each country.

Indigenous children were taken from their families, sometimes literally ripped from their parents’ arms, and forced to stay at residential schools for months or even years at time without contact with their families.

Some children who went to residential schools were never seen by their families again. Unmarked graves of children are still being uncovered near former residential schools in Canada as the country concludes a years-long, national ‘Truth and Reconciliation Process’ to “facilitate reconciliation among former [residential school] students, their families, their communities and all Canadians” (Government of Canada, 2021). September 30, 2021 was the first time Canadians observed a now-annual ‘National Day of Truth and Reconciliation’ to “focus the country’s attention on the victims and survivors of the residential school system and other genocidal acts against Indigenous peoples” (Atkins, 2021).

In October 2021, President Joe Biden issued a proclamation commemorating Indigenous People’s Day in the United States on what is also known as Columbus Day (celebrated on a Monday each October) (Judd, 2021). President Biden’s proclamation does not end the federal government’s celebration of Columbus Day, though a number of cities in the U.S. have opted to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous People’s Day (Judd, 2021).

In September 2021, Senator Elizabeth Warren revealed a bill called The Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States Act (Bendery, 2021).

“The commission would provide a forum for Native people to speak about their families’ personal experiences with boarding school atrocities, and would come up with recommendations for Congress to help Indigenous people heal from the “historical and intergenerational trauma” passed down in their families.

The Indian Boarding School Policies are a stain in America’s history, and it’s long overdue that the federal government reckon with this history and its legacy,” Warren said in a statement. “These policies and practices caused unimaginable suffering and trauma for survivors, victims, and the thousands of Native families who remain impacted by them (Bendery, 2021).” For the full article on Senator Warren’s propose legislation follow the link here.

As you watch the following video clips of a detailed history, timeline and description of the residential school system in Canada and the stories of residential school survivors, reflect on how the beliefs and policies driving residential school system and Indigenous children’s and families’ experiences of residential school systems illustrate the key concepts we have discussed in this course and this section in particular, including:

- Direct, structural and cultural violence

- Interpersonal racism

- Systemic racism

- Cultural genocide

- Intergenerational trauma

- Historical, structural and social determinants of health

Trigger warning: The following videos discuss concepts and experiences some individuals may find triggering and upsetting, including instances of interpersonal and structural racism, violence and cultural genocide against children.

It is highly recommended you view both of the following video clips.

The way forward: What can be done to combat the negative effects of racism and intergenerational trauma on health?

Note: The following section adapted from (Smedley et al, 2010), (CDC, 2021) and (Canadian Medical Association and the Government of Northwest Territories, 2021) as and where noted in in-text citations at the end of each section attributed to each author.

We’ve seen how inequities in various arenas of our lives—in our neighborhoods, schools, jobs, housing and income—along with discrimination and internalized racism, can produce inequities in health outcomes. But research suggests many public policies that can improve the status and thus the health and well-being of peoples of color while advancing us further down the road to a non-racial society. Importantly, these policies don’t assume that U.S. society is “color-blind;” rather, they acknowledge that race, while not a biological reality, too often shapes life opportunities and health because of the lived experience of race.

How, then, can policy ameliorate the effects of racism on health? The United States has made great progress in improving race relations and attitudes toward racial diversity in the four-plus decades since landmark federal civil rights and voting rights legislation. But laws alone have not created equal opportunity for all, nor have they eliminated implicit racial bias and stereotyping. Below are just a few examples of innovative policies that can expand opportunity for all, while creating structures that root out implicit bias and more subtle forms of discrimination.

Because one of the fundamental determinants of racial and ethnic health disparities is segregation and unequal living conditions in majority-white and majority-minority neighborhoods, housing mobility strategies are a promising approach to reducing health inequities and expanding opportunity. Research suggests that helping poor people of color relocate to lower poverty neighborhoods can improve health outcomes, although more research is needed to understand how and under what conditions programs work best. Portable rent vouchers and tenant-based assistance are the most common housing mobility strategies, but legal efforts that challenge residential and school segregation have also produced results. Rigorous enforcement of antidiscrimination and equal opportunity laws remains critical to prevent redlining and ensure fair lending practices, including protection from sub-prime home loans. One obstacle, however, remains white flight from middle class destination communities.

While increasing housing options for people of color is one important strategy, policies should not ignore the needs of majority-minority communities. Many such communities, as noted above, are segregated from opportunity in ways that ultimately harm the health of their residents. To address these problems, policies should be examined that reduce geographic barriers to opportunity. For example, new job creation is increasingly taking place in suburban and exurban communities, far from segregated communities of color in urban cores and inner-ring suburbs; many of the residents in these communities don’t have cars or other opportunities to get to these jobs. A range of public policies – including public transportation, economic empowerment zones, housing mobility, and zoning – can reduce the distance between people and employment opportunities. Most of these policies require regional planning and coordination across local jurisdictions, and can be supported by state and federal incentives.

Communities of color can also benefit from improving community resources for health and reducing environmental risks. Several strategies can improve the health of communities, such as improving coordination of key federal and state agencies involved in arenas that affect health (e.g., education, housing, and employment), creating incentives for better food resources in underserved communities (e.g., major grocery chains, farmer’s markets), developing community-level interventions for the promotion of healthy behavior (e.g., smoking cessation, exercise), and addressing environmental health threats (e.g., aggressive monitoring and enforcement of environmental laws).

In addition to providing housing mobility options and improving health and life opportunity conditions in communities of color, it’s important to consider all aspects of opportunity when fashioning new policies and programs that will affect Americans’ life chances. To that end, government can use a new policy tools, such as an “Opportunity Impact Statement” (OIS) as a requirement for publicly funded or authorized projects like school, hospital, or highway construction, or the expansion of the telecommunications infrastructure. Like an environmental impact report, an OIS would predict, based on available data, how a given effort would expand or contract opportunity in terms of equitable treatment, economic security and mobility, and shared responsibility, and it would require public input and participation. Government can also make expanding opportunity a condition of its partnerships with private industry by requiring, for example, public contractors to pay a living wage tied to families’ actual cost of living, insisting on employment practices that promote diversity and inclusion, and ensuring that new technologies using the public electromagnetic spectrum include public interest obligations and extend service to all communities.

Importantly, however, government policies should also restore a commitment to human and civil rights in ways that acknowledge how bias and discrimination play out at interpersonal levels, often in subtle ways that neither party may recognize. Some of the greatest strides in advancing American opportunity emerged from the twentieth century movements for racial equality, women’s rights, and workers’ rights, and new policies are needed to build upon these. This work is not yet complete; what is needed is both vigorous enforcement of existing anti-discrimination protections and a new generation of human rights laws that address evolving forms of bias and exclusion.

These include:

- Increasing the staffing and resources that federal, state, and local agencies devote to enforcing anti-discrimination laws in voting, employment, housing, education, lending, criminal justice and other spheres. This includes using data more effectively to better detect potential bias, for instance, by comparing workforce diversity with the composition of an area’s qualified workforce.

- Assisting employers and other institutions committed to providing a fair and diverse environment, for example, by promoting model performance evaluation practices, greater cultural fluency, and other tools to counter bias and exclusion.

- Crafting new human rights laws that complement existing civil rights protections by addressing subconscious and institutional biases more effectively, protecting economic and social rights like the right to education, and correcting exclusion based on socioeconomic status and other characteristics not fully covered by current laws (Smedley et al, 2010).

Another example of actions and interventions to address and eliminate the negative impact of historic and systemic racism comes from the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The Canadian TRC completed its process with specific calls to action within different domains to address racism and its effects on Indigenous people; a number of those calls to action are specifically focused on health.

The following are taken from TRC documents and were reported in The Unforgotten Toolkit (Canadian Medical Association and the Government of Northwest Territories, 2021).

The TRC Calls to Action 18-24 are focused on health and include:

• Federal, provincial and territorial governments acknowledging that health care inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians exist due to previous Canadian government policies, including Residential Schools.

• The federal government, in consultation with Indigenous peoples, establishing measurable goals to close the gap in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, and publishing annual reports and assessing long-term trends.

• The federal government recognizing and addressing the distinct needs of urban Indigenous populations.

• The federal government providing funding for existing and new Indigenous healing centres.

• All those who can effect change in health care systems recognizing the value of Indigenous healing practices.

• All levels of government increasing the number of Indigenous professionals working in health care, increasing retention of Indigenous professionals working in health care, and providing

cultural competency training for all health care professionals.

• Development of a mandatory course on Indigenous history for all medical and nursing schools.

There have been incremental changes as institutions take steps to implement the calls to action and recommendations outlined in these reports and inquiries.

For example, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine addressed 19 of the calls to action linked to health care and education training through a series of commitments, including the establishment of an Indigenous health lead to support all programs in incorporating Indigenous health in their clinical and academic curriculum.

Conversely, health care institutions can apply some of these calls to action by:

• Acknowledging health care inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians;

• Addressing the distinct needs of urban Indigenous populations in their practices;

• Recognizing the value of Indigenous healing practices;

• Enrolling staff in mandatory courses on Indigenous history, and

• Reviewing hiring practices to encourage hiring more Indigenous professionals.

(Canadian Medical Association and the Government of Northwest Territories, 2021).

Racial and ethnic health disparities are real and persistent. Although today’s problems may be deeply rooted in the past, what’s important is that they threaten our future health and well-being. Simply put, many people of color live shorter lives and suffer poorer health than white Americans. But this is not inevitable. We have the power to change health outcomes. The bad news is that our health problems cannot be solved overnight, with better health care or newer drugs. The good news is that the solutions have been with us all along: evidence suggests that if we work towards social justice, people’s health, everyone’s — not just for those on the bottom – will improve as a result (Smedley et al, 2010).

NOTE: PUBH110 Asynchronous/online students, after reading Section 3.16: Racism as a Determinant of Health, be sure to proceed to the course Blackboard site and the Learning Content for Section 3.16. You have additional reading and a series of short films (~40 minutes total) to watch which are required in order to adequately respond to this weeks’ Case Study.

PUBH110 In Person students we will view films in class.

References

- Atkins, CJ. (2021). Canada observes first ‘Reconciliation Day’ recognizing Indigenous genocide and oppression. People’s World. https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/canada-observes-first-reconciliation-day-recognizing-indigenous-genocide-and-oppression/

- Barnshaw, J. (2008). In Richard T. Schaefer (ed). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity and Society Vol 1. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com/booksid=YMUola6pDnkC&pg=PT1217&dq=race+social+construction#v=onepage&q=race%20social%20construction&f=false

- Bendery, J. (2021). Elizabeth Warren Unveils Bill to Document Indian Boarding School Atrocities. Huffpost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/elizabeth-warren-native-boarding-schools_n_615605b2e4b0502542304b42?ncid

- Bhopal, R. (2016). Book Summary: Migration, Ethnicity, Race and Health. Public Health Panorama. Vol 2: 4. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/330731/10-Migration-ethnicity-race-health.pdf

- Bilsky, L. and Klagsbrun, R. (2018). The Return of Cultural Genocide? European Journal of International Law. Vol 29:2. https://academic.oup.com/ejil/article/29/2/373/5057075

- Canadian Medical Association and the Government of Northwest Territories. (2021). The Unforgotten toolkit: an educational guide. https://theunforgotten.cma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/CMA-IFSToolkit-AODA-June-3-v2-EN.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). CDC’s Efforts to Address Racism as a Fundamental Driver of Health Disparities. Health Equity. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/racism-disparities/cdc-efforts.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). Impact of Racism on our Nation’s Health. Health Equity. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/racism-disparities/impact-of-racism.html

- Colvin, R. and Murphy, Z. (2020). We’ve Been Failed. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/black-chicagoans-covid-19-high-death-rate-system-of-neglect/

- Government of Canada. (2021). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525

- Judd, D. (2021). Biden becomes first president to issue proclamation marking Indigenous Peoples’ Day. CNN Politics.

- https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/08/politics/indigenous-peoples-day-joe-biden/index.html

- Novic, E. (2016). The concept of cultural genocide: an international law perspective. Cultural Heritage Law and Policy. Oxford University Press: New York. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/43864

- Rice, J. (2011). Indian Residential School Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Cultural Survival. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/indian-residential-school-truth-and-reconciliation

- Smedley, B., Jeffries, M., Adelman, L. and Cheng, J. (2010). Race, Racial Inequality and Health Inequities: Separating Myth from Fact. The Opportunity Agenda. https://unnaturalcauses.org/assets/uploads/file/Race_Racial_Inequality_Health.pdf