2. Key Concepts

- Sex

- Gender

- Gender vs sex

- Gender identity

- Gender norms

- Women’s health

- Maternal mortality

- Adolescent pregnancy

- Safe abortion

- Unsafe abortion

- Post-Abortion Care

- Female Genital Cutting

- Violence against women

- Intimate partner violence

- Sexual violence

3. Prelim Engagement

1. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2010) recognizes that gender is an important determinant of health in two dimensions:

1) gender inequality leads to health risks for women and girls globally; and

2) addressing gender norms and roles leads to a better understanding of how the social construction of identity and unbalanced power relations between genders affect the risks, health-seeking behaviour and health outcomes of people who identify as men, women and transgender (Men et al, 2013, p. 22). However, how exactly can gender have an impact on health? Does it relate to gender inequality as a social determinant of health?

Please watch the following videos to get you acquainted with the concepts and challenges in the field. As you watch, reflect on potential personal experiences, or stories you have heard from family and friends, or cases you have read in the news. Try to recognize gendered challenges, discussions related to gender and health incidents you or someone from your social circle experienced. Reflect on the importance of getting a deeper understanding of gender as an important social determinant of health within healthcare, Public and Global Health contexts.

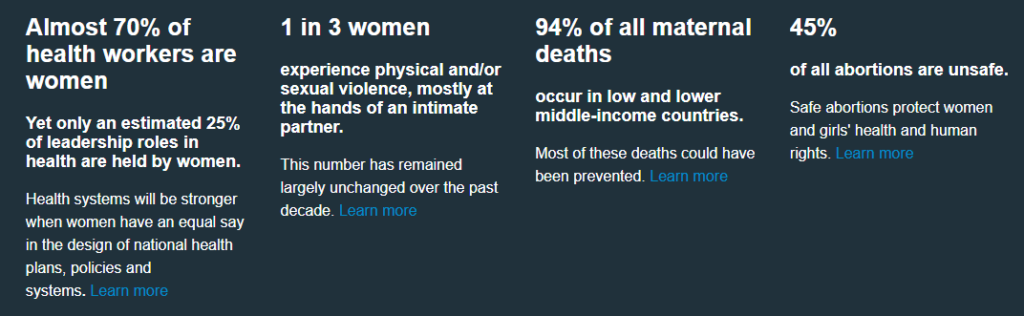

2. In this section we will focus a lot on maternal health, including maternal mortality. Watch this video clip to understand more about the global challenge of maternal mortality. While maternal mortality continues to be a problem in high-income countries, especially in the United States, 94% of maternal deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Using the knowledge you have gained over the course of the semester thus far, you should be able to identify this unequal distribution of maternal mortality rates between countries as a health inequity and a health disparity.

3. Why are women dying?

We will explore the leading causes of maternal death and risks to women’s health globally in more detail in the reading below. First, to better understand the reality of seeking out maternal health care for millions of women around the world in low- and middle-income settings, watch this clip about Chanceline --- a woman who lives in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and who is pregnant with her second child.

This documentary was shot by a Dutch film crew for a Dutch NGO in eastern DRC. The film crew followed Chanceline on the walk from her home to the nearest health center where she went for antenatal care --- or the medical visits women are recommended to have during their pregnancy to monitor their health and the health of their baby. Notice how long this video is --- yes, more than 5 hours long. Chanceline has to walk five hours in one direction to reach the nearest health facility.

We are not asking you to watch the entire 5 hour film --- the first 3 minutes of the film will give you an idea of Chanceline’s journey. Later in the film she has to walk in heat and while it rains --- and this is only one way. She has to make the journey home, by foot, after her appointment as well.

While watching these first 3 minutes of Chanceline’s journey, reflect on the historical, structural and social determinants of health contributing to this situation for Chanceline and women like her around the world. Also think about the direct and indirect costs of this visit to the health center for her --- can her husband work in their fields while she is away if he has to take care of their younger child? What about the risks to her health from walking for more than 10 hours to reach the health center and return home? What will she do once she is ready to have her baby? What if she cannot make the 5 hour walk while in labor to the health center? These are questions that many households around the world face every day, and are all determinants of health contributing to persistent high rates of maternal mortality --- and other health challenges --- around the world.

Trigger warning: This section of reading covers topics which may be triggering or upsetting to readers, including gender-based violence, sexual violence and sexual coercion.

Start with the basics: Sex and gender, not the same

Sex and gender are often used interchangeably, but the two concepts are very different. Let’s begin our discussion about gender as a determinant of health by differentiating sex from gender.

For the purpose of this course, we will adopt the following definitions, which will constitute a basis to better understand women’s, men’s and transgender people’s concerns and experiences, including health.

OK, so what are we referring to when we talk about a person’s sex?

“Sex” refers to the physical differences between people who are male, female, or intersex. A person typically has their sex assigned at birth based on physiological characteristics, including their genitalia and chromosome composition. From the time that sex is assigned, an individual’s sex becomes a social and legal fact.

Council of Europe, 2021

OK, so then what is gender?

While sex is a biological characteristic, gender is a social and cultural concept. You will often hear that ‘gender is socially constructed.’

Gender refers to the cultural roles, behaviors, activities and attributes expected of people based on their [biological] sex.

CDC, 2019

Gender is often described using the terms woman, man and non-binary (not identifying strongly with either gender), though individuals may define their gender in other ways as well.

Gender norms, roles and relations vary from society to society and evolve over time. They are often upheld and reproduced in the values, legislation, education systems, religion, media and other institutions of the society in which they exist.

When individuals or groups do not “fit” established gender norms they often face stigma, discriminatory practices or social exclusion – all of which adversely affect health. Gender is also hierarchical and often reflects unequal relations of power, producing inequalities that intersect with other social and economic inequalities. (World Health Organization, 2011).

Gender identity refers to the gender to which persons feel they belong, which may or may not be the same as the sex they were assigned at birth. It refers to each person’s deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender and includes the personal sense of body and other expressions, such as dress, speech and mannerisms.

Council of Europe, 2018

In many (though not all) cultures, individuals are assigned a gender at birth based on their biological sex (primarily the genitals they are born with). For example, an individual born with a penis in the United States would in most cultural circumstances be referred to as a boy or man from birth using he/him pronouns. However, this person might decide at a young or older age that they are more comfortable living in the world using she/her pronouns and adopting different behaviors or ways of presenting themselves socially than the dominant cultural definition of a man.

Gender roles will be defined differently by different cultures and by different individuals.

Even as we are emphasizing that sex and gender are not the same concept and should not be used interchangeably, you will see that much of the medical, Public and Global Health literature often do use the terms ‘men and women’ when they are actually referring to ‘males and females.’ As you read through this section keep this in mind — sometimes as you are reading about ‘women’, for example, the text might actually be referring to females as a biological sex.

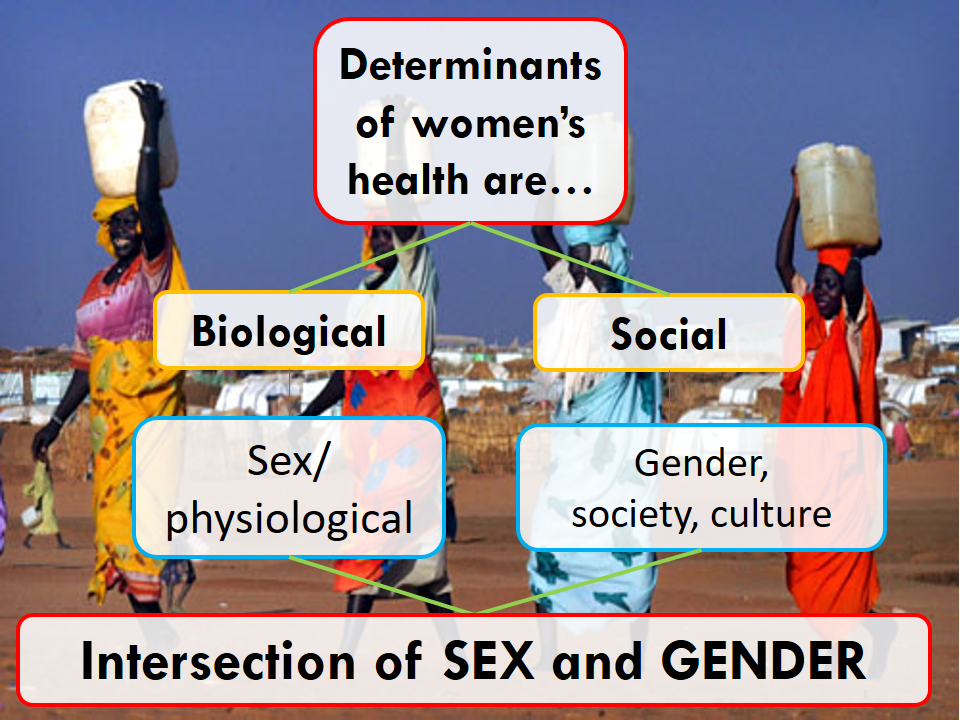

The intersection of sex and gender for health outcomes

Sex and gender interact in complex ways to affect health outcomes.

As we discussed in a previous section of reading, there are both biological and social determinants of health. When we talk about gender as a determinant of health, we must look at how biological determinants of health such as sex intersect with social determinants of health — such as gender. The health outcomes related to gender as a determinant of health sit at this intersection of biology (sex) and social context (gender).

Sex (male or female) can affect disease risk, progression and outcomes through genetic (e.g. function of X and Y chromosomes), cellular and physiological (e.g. hormonal) pathways. These pathways can produce differences in susceptibility to disease, progression of disease, treatment and health outcomes, and are likely to vary over the life-course.

For example, data shows that males experience more severe COVID-19 outcomes in terms of hospitalizations and deaths than females. This is, in part, explained by higher quantities of an enzyme found in males, which binds to the SARS-COV2 virus. In another example, we know that breast cancer is about 100 times more common in females than males (though males can develop breast cancer) (American Cancer Society, n.d.). While females generally tend to have more breast cells than men, the main risk factor for cancer for females is higher production of the hormones estrogen and progesterone (American Cancer Society, n.d.). These are examples of biological determinants of health related to sex.

While biology is an important determinant of health, we have discussed in detail in this course how structural and social determinants are also important considerations in understanding health outcomes. Gender norms (man, woman, non-binary or other gender identities), socialization, roles, differentials in power relations and access to and control over resources are all structural and social factors which contribute to health outcomes.

Gender norms are social principles that govern the behavior of girls, boys, women, and men in society and restrict their gender identity into what is considered to be appropriate. Gender norms are neither static nor universal and change over time. Some norms are positive, for example, the norm that children shouldn’t smoke. Other norms lead to inequality.

Save the Children, 2021

For example, data show that men’s increased risk of acquiring SARS-COV2 is also linked to their lower rates of handwashing, higher rates of smoking and alcohol misuse and, related to that – higher comorbidities for severe COVID-19 symptoms as compared to women (WHO, 2021). Studies have also shown that in some contexts women are more likely to seek out health services, especially preventive health services, for physical and mental health concerns than men (Thompson et al, 2016, ). In some socio-cultural contexts, mothers were more likely to seek out more expensive healthcare services for boy newborns than girl newborns (Willis et al, 2009; Ismail et al, 2019). These are examples of social determinants of health related to gender.

We will revisit these and other examples in more detail as we move through this section. While the topic of ‘gender as a determinant of health’ applies to women, men and trans-identifying people we will explore women’s health in this course.

Women’s Health

What do we mean by ‘Women’s Health’?

Gender has implications for health across the course of every person’s life. Gender can influence a person’s experiences of crises and emergency situations, their exposure to diseases and their access to healthcare, water, hygiene and sanitation.

Gender as a determinant of health functions very differently for men, women and individuals with other gender identities. Between men and women, however, gender inequality disproportionately affects women and girls. People who identify as transgender also have very specific determinants of health, experiences of discrimination and health needs accessing the care that they need.

A note on pronouns & pregnancy

Much of the literature on women’s and maternal health refers exclusively to ‘women.’ However, individuals who are biologically female but who identify their gender as men, transgender or otherwise also have health needs and experience health challenges that many biolgoical female, women-identifying individuals do. For example, transgender men (biological females who live in the world as men) can have cervical cancer and are able to become pregnant and have children.

It is true that the vast majority of individuals who, for example, have cervical cancer or become pregnant globally are biologically female and identify as women. But, we want to be sure to recognize that not all individuals experience female health realities are women. For example, not all individuals around the world who become pregnant around the world identify as women — and these individuals can experience very particular challenges to accessing the safe care that they need during pregnancy, during childbirth and in the post-partum period due to individual and systemic discrimination.

Some [optional] reading resources on transgender pregnancy are listed here:

Transgender Pregnancy: Moving Past Misconceptions

In most societies around the world women and girls have lower social status, economic and political power and less control over decision-making about their bodies, in their intimate relationships, families and communities compared to men. This gender power differential puts women at higher risk for experiencing violence, coercion and harmful practices than men.

Gender based power differentials refer to the social roles and power relations between men and women.

Solanke, 2019

Think again about how female biology intersects with the gender roles assigned to women in many contexts around the world.

What are some biological risk factors related to female health?

Note this is not an exhaustive list!

- Menstruation can put females at risk for anemia

- Pregnancy and birth have a number of health risks

- Females are more susceptible to sexually transmitted infections than men

- Vaginal mucosal surfaces are larger and more vulnerable to sexual secretions than males’ mostly skin-covered penis (FHI 360, n.d.)

- Sexually transmitted infections are often asymptomatic in females so go unnoticed/ untreated for longer

- Untreated sextually transmitted infections increases risks of contracting HIV

- Females are more susceptible to certain cancers than males, such as breast cancer and cervical cancer

Now, what about social risk factors — in this case gender-related risk factors — linked to women’s health?

Identifying as a man or a woman has a significant impact on health. The health of women and girls is of particular concern because, in many societies, women and girls are disadvantaged by discrimination rooted in sociocultural factors.

Some of the sociocultural factors that prevent women and girls from benefiting from quality health services and attaining the best possible level of health include:

- unequal power relationships between men and women;

- social norms that decrease education and paid employment opportunities for women and girls;

- an exclusive focus on women’s reproductive roles (ie women are only or mostly valued because they can have children and other health issues are not prioritized); and

- potential or actual experience of physical, sexual and emotional violence.

Increased biological risk of Sexually Transmitted Infections/ Diseases (STDs) for Females

[Females] are also biologically more vulnerable to STDs than are [males]. [Females] are more susceptible to STDs during sexual intercourse because the vaginal surface is larger and more vulnerable to sexual secretions than the primarily skin-covered penis.

Also, the volume of potentially infected male ejaculate deposited in a female’s vagina during intercourse is larger than the potentially infected cervical and vaginal secretions to which men are exposed.

STDs in [females] tend to go untreated because they are often asymptomatic. As already noted, an untreated STD increases susceptibility to HIV infection.

(FHI, n.d. https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/webpages/Modules/STD/s1pg22.htm)

Cultural and social gender power differentials which dis-empower women can result in:

- Unequal treatment of girls and boys from infancy (ie boys receiving better or more food, boys being prioritized for education, early marriage of girls)

- Women’s limited access to financial resources

- Women’s limited decision making power in their household

- Women’s inability to travel freely or to access transportation

- Women’s increased risk of experiencing verbal, physical, sexual or emotional violence

- Women’s inability to refuse to have sex with a male partner or negotiate the use of contraception including condoms

And we must ask ourselves — how do each of the factors above impact women’s safety, well-being, access to health services and, therefore, health outcomes?

A major aim of this section of reading is to understand how and when biological risk factors for females intersect with gender roles and power differentials assigned to and experienced by women — and how that intersection of biology and gender results in a number of health risks unique to females who identify as women.

Women and girls face high risks of unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections including HIV, cervical cancer, malnutrition and depression, amongst others. Gender inequality also poses barriers for women and girls to access health information and critical services, including restrictions on mobility, lack of decision-making autonomy, limited access to finances, lower literacy rates and discriminatory attitudes of healthcare providers (WHO, 2021a).

Women’s health as a human right

Women’s sexual and reproductive health is related to multiple human rights, including the right to life, the right to be free from torture, the right to health, the right to privacy, the right to education, and the prohibition of discrimination.

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) have both clearly indicated that women’s right to health includes their sexual and reproductive health.

This means that States have obligations to respect, protect and fulfill rights related to women’s sexual and reproductive health. The Special Rapporteur on the right to health maintains that women are entitled to reproductive health care services, and goods and facilities that are:

- available in adequate numbers;

- accessible physically and economically;

- accessible without discrimination; and

- of good quality (UN, 2006).

Despite these obligations, violations of women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights are frequent. These take many forms, including:

- denial of access to services that only women require;

- poor quality services;

- subjecting women’s access to services to third party authorization;

- forced sterilization, forced virginity examinations, and forced abortion, without women’s prior consent;

- female genital mutilation (FGM) [author’s note: including FGM/C in this list of human rights violations is very loaded within the global community; please see section below on FGM/C for more context]; and

- early marriage.

Causes and consequences of sexual and reproductive health violations

Violations of women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights are often due to deeply ingrained beliefs and societal values pertaining to women’s sexuality. Patriarchal concepts of women’s roles within the family mean that women are often valued based on their ability to have children. Early marriage and pregnancy, or repeated pregnancies spaced too closely together—often as the result of efforts to produce male offspring because of the preference for sons—has a devastating impact on women’s health with sometimes fatal consequences.

Examining Key Issues in Women’s Health: A Global Perspective

The breadth and depth of women’s health challenges is too great to completely explore in this space. However, there are a number of women’s health challenges which are especially prioritized in the field of global health. We explore a selection of these issues below.

To learn more about these and other priority issues for Women’s Health visit the World Health Organization’s page here.

As you read this excerpt, think back to our discussions about the determinants of health — what were the relationships we explored between education and health?

Can you think of short- and long-term health consequences of girls not attending school?

Inequity from the beginning: Gender norms, gender roles and girls’ education

Sadly, girls around the world are kept from attending school in favor of gender norms related to their role in household chores and the position of girls in society. Their voices are undervalued if heard at all. Their childhoods are stolen, and the countries where they live are robbed of their talent and potential.

This reduced access to education has long-term consequences for the future of girls. Inequality cuts girls’ futures short – when girls are excluded from receiving an education, their ability to earn a living and become independent is drastically limited. Without equal opportunities to learn, income inequality and dependence on men to provide keeps girls in a cycle of poverty and confinement to their homes to perform unpaid domestic labor. Lack of outside opportunities limits the ability of girls to reach their ambitions.

In extreme scenarios, such as in sub-Saharan Africa and Western Asia, girls of every age are more likely to be excluded from education than boys. For every 100 boys out of school in these regions, 115 and 123 girls, respectively, are denied the right to education due to deeply ingrained gender norms.

(Save the Children, 2021)

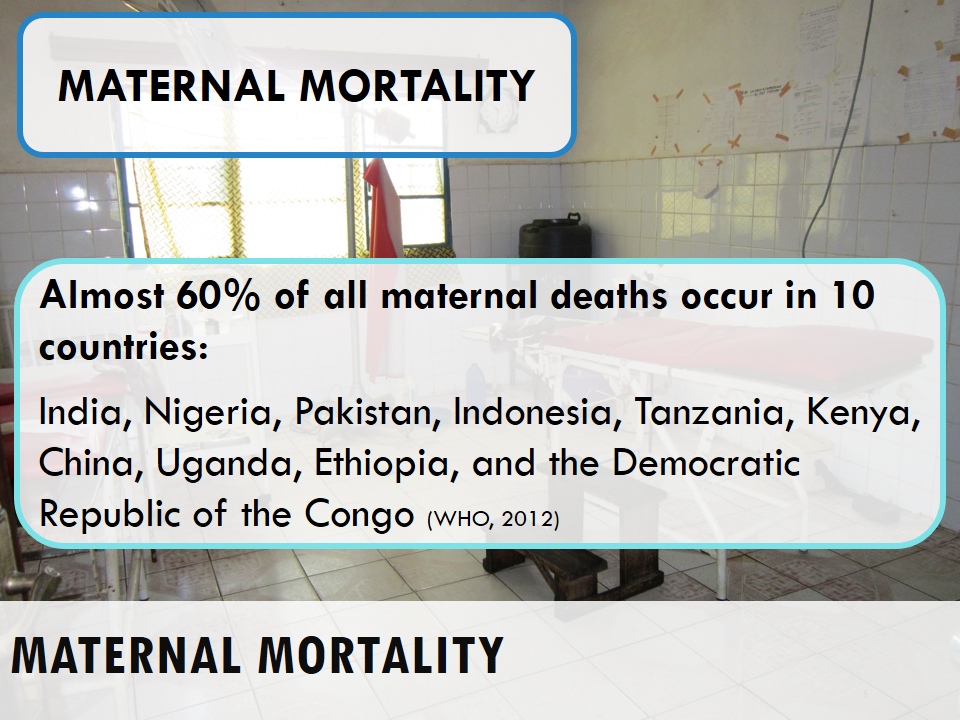

Maternal Mortality

(NOTE: Excerpts from this section attributed to Roser and Ritche, 2013)

Reducing maternal mortality is one of the highest priorities on the Global Health agenda.

Maternal Death is defined as a female death related to pregnancy and childbirth or within the first 42 days of termination of pregnancy.

WHO, 2021b

*Measuring the Burden of Disease reminder*

Maternal mortality ratio is the number of women who die as a result of pregnancy and childbirth complications per 100,000 live births (CDC.gov).

For most of our history, pregnancy and childbirth were dangerous for both baby and mother. Improvements in healthcare, nutrition, and hygiene mean maternal deaths are much rarer today.

Between 2000 and 2017, the maternal mortality ratio dropped by about 38% worldwide: from 451,000 maternal deaths in 2000 to 295,000 maternal deaths in 2017 (WHO, 2019).

Despite these fantastic gains, too many women are still dying from pregnancy-related causes.

The biggest tragedy is that most maternal deaths are preventable, even in resource-poor settings.

The WHO estimates that everyday in 2017, approximately 810 women died from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth — that equals 295,000 women who died in 2017 alone (2019).

As the map below clearly shows, 94% of all of these maternal deaths occur in low and middle income countries (WHO, 2019).

Play the animated graph to see where improvements in maternal mortality ratios were made from 2000-2017.

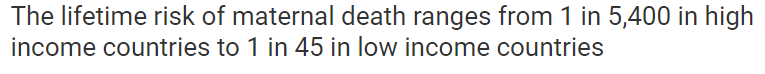

Women in high income countries have a 1 in 5,400 lifetime risk of dying from a maternal death while women in low income countries have a 1 in 45 risk of dying from a maternal death (WHO et al 2019b).

To understand the figure and statistics below, think in terms of the lottery. If you have a 1 in 45 chance of winning the lottery and your friend has a 1 in 5,400 chance of winning the lottery, which one of you has a higher chance of winning? You do, because 1 in 45 is a much higher chance than 1 in 5,400.

Unfortunately in the example of global maternal death, we are not talking about winning. We are talking about women dying of mostly preventable causes. Therefore, as you read the statistics below, women in regions with the lower denominator (the denominators in the examples above are 45 and 5,400) have a higher chance of dying a maternal death in their lifetime.

Given your Global Health knowledge, does this distribution of maternal deaths between countries look like a health inequality or a health inequity?

If you said ‘health inequity’, you are correct. The fact that almost all maternal deaths globally occur in low- and middle-income countries from preventable causes is unjust, unfair and avoidable — our definition of inequity.

Watch the following short videos to learn more about the leading causes of maternal mortality as well as the steps low- and middle-income countries are taking to reduce the burden of this health disparity.

Note that some statistics in the videos are slightly outdated (ie In the past 99% of maternal deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries. That percentage has now reduced to 94%).

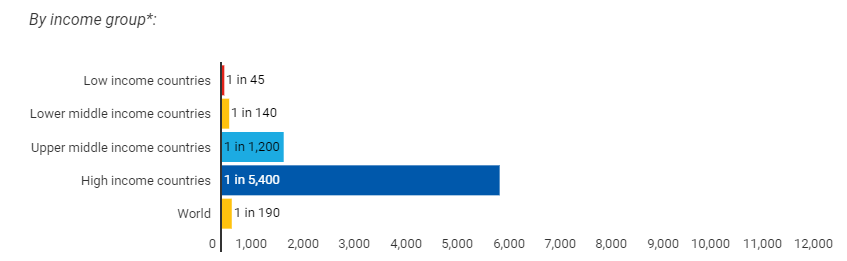

Maternal mortality: not just a ‘third world’ problem

While almost all maternal deaths globally occur in low- and middle-income countries, some high income countries still have maternal mortality rates which are unacceptably high. The United States, for example, has one of the highest maternal mortality rates among high income countries in the world.

Optional Reading: Maternal Mortality trends in the United States

With the advancement of modern medicine, maternal deaths while giving birth are becoming increasingly rare in many developed countries across the world. Still, while high-income countries generally correlate positively with lower maternal mortality rates, the U.S. stands out as having an abnormally high rate of maternal deaths globally despite their vast wealth and medical technology. New data shows just how far the U.S. leads other developed countries in maternal deaths.

According to a recent report from the Commonwealth Fund, the U.S. has nearly double the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births compared to other wealthy, developed nations. At 17.4 per 100,000, the U.S. leads countries like France and Canada with roughly 100 percent more deaths per capita. Other countries, like the Netherlands., Germany and Norway, are below three deaths per 100,000.

The report goes on to show how a large number of maternal deaths occur after birth, with some deaths occurring shortly after birth or months after due to internal complications. Infection, severe bleeding and high blood pressure are some of the leading causes for postpartum death in the U.S.

Other data in the report illustrates how the U.S. has much less midwives per capita than other developed countries. The U.S. and Canada were some of the only developed countries with more OB-GYN doctors compared to midwives, with countries like Sweden and Australia having 66 and 68 midwives per 1,000 live births, respectively, compared to just 4 for both the U.S. and Canada.

(Statista, 2020)

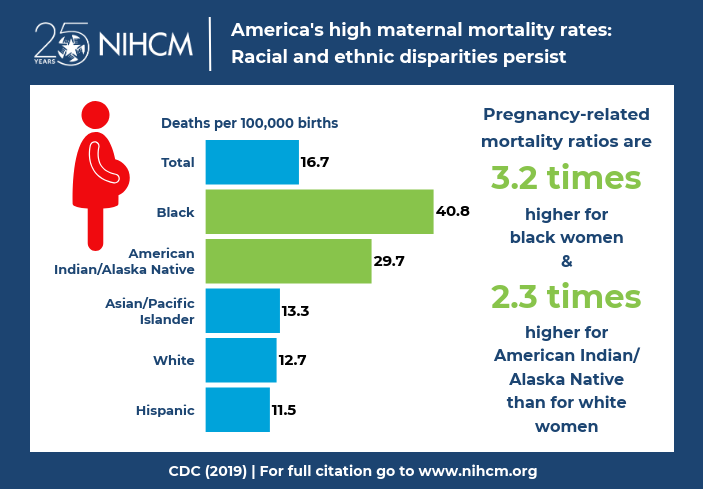

The reality of maternal mortality in the United States becomes even worse when we consider maternal mortality rates by race and ethnicity. Think back to our discussions of the structural and social determinants of health, including racism as a determinant of health. Maternal mortality in the United States paints a very real picture of the consequences of social, economic, political and health inequities.

Looking at the statistics below for maternal mortality in the United States by race and ethnicity, would you say the distribution of maternal mortality by race and ethnicity is an inequality or an inequity?

By now in the semester you should be able to identify this grossly uneven distribution of maternal mortality by race and ethnicity in the United States as a health inequity.

The following video clips uncover the inequities in maternal mortality in the United States in more detail. While all videos are recommended, we ask that you watch at least two of the four clips — one on maternal mortality of Black Americans and one on maternal mortality of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives.

As you watch these videos, which historical, structural and social determinants of health can you identify that impact Black and Native Americans’ birth experiences and higher risks of maternal mortality in the United States?

Pay special attention to the effects of institutional and internalized racism of medical providers and the medical system in the United States that affect racialized and systematically marginalized pregnant people.

Further [optional] Reporting on Maternal Mortality in the United States

In 2018, National Public Radio completed a series on maternal mortality in the United States. This series explores maternal mortality across races, and is an in-depth analysis of medical culture in the United States that impacts the ways in which women are treated during pregnancy, childbirth and in the post-partum periods.

NPR Special Series LOST MOTHERS: Maternal Mortality in the U.S.

Why are women dying?

The Leading Causes of Maternal Mortality Globally

Women die as a result of complications during and following pregnancy and childbirth. Most of these complications develop during pregnancy and most are preventable or treatable. Other complications may exist before pregnancy but are worsened during pregnancy, especially if not managed as part of the woman’s care.

Remember, a maternal death can occur during pregnancy, during or immediately after childbirth or in the period following child birth (typically considered up to 6 weeks or 42 days, referred to as the postpartum period).

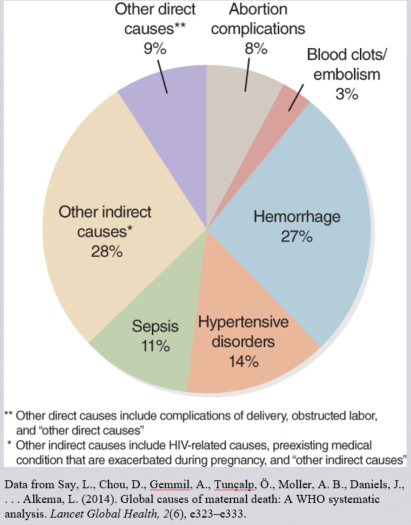

The major complications that account for nearly 75% of all maternal deaths are:

- Severe bleeding also referred to as hemorrhage (mostly bleeding after childbirth)

- Infections also referred to as sepsis (usually after childbirth)

- High blood pressure during pregnancy (also referred to as hypertensive disorders including pre-eclampsia and eclampsia)

- Complications from delivery and

- Unsafe abortion.

The remainder are caused by or associated with infections such as malaria or related to chronic conditions like cardiac diseases or diabetes.

The graph below charts the decline in maternal deaths by cause from 1990 to 2016. Note in particular the significant drop in number and percentage of maternal death by hemorrhage.

This pie chart gives another visual of the leading causes of maternal deaths.

Most maternal deaths are preventable, as the health-care solutions to prevent or manage complications are well known. All women need access to high quality care in pregnancy, and during and after childbirth. Maternal health and newborn health are closely linked. It is particularly important that all births are attended by skilled health professionals, as timely management and treatment can make the difference between life and death for the mother as well as for the baby.

Severe bleeding or ‘hemorrhage’ after birth can kill a healthy woman within hours if she is unattended. Injecting oxytocics immediately after childbirth effectively reduces the risk of bleeding.

Infection or ‘sepsis’ after childbirth can be eliminated if good hygiene is practiced and if early signs of infection are recognized and treated in a timely manner.

Pre-eclampsia should be detected and appropriately managed before the onset of convulsions (eclampsia) and other life-threatening complications. Administering drugs such as magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia can lower a woman’s risk of developing eclampsia (WHO, 2019a).

Unsafe abortion specifically is explored in further detail in a section below. An abortion is considered unsafe when it is carried out either by a person lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both (WHO, 2020a).

Why do women not get the care they need while pregnant, giving birth or in the post-partum period?

Poor women in remote areas are the least likely to receive adequate health care. This is especially true for regions with low numbers of skilled health workers, such as sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (WHO, 2019a).

The latest available data suggest that in most high income and upper middle income countries, more than 90% of all births benefit from the presence of a trained midwife, doctor or nurse. However, fewer than half of all births in several low income and lower-middle-income countries are assisted by such skilled health personnel.

The main factors that prevent women from receiving or seeking care during pregnancy and childbirth are:

- Poverty

- Distance to facilities

- Lack of information

- Inadequate and poor quality services

- Cultural beliefs and practices (WHO, 2019a).

Also think back to the clips you watched about maternal mortality in the United States — think of other historical, structural and social determinants of health such as racism and discrimination in their different forms which affect pregnant individuals around the world in different contexts.

To improve maternal health, barriers that limit access to quality maternal health services must be identified and addressed at both health system and societal levels (WHO, 2019a).

Adolescent pregnancy and early (or child) marriage

Note: The following section is adapted from WHO: Adolescent Pregnancy (2020b)

Every year, an estimated 21 million girls aged 15–19 years in developing regions become pregnant and approximately 12 million of them give birth.

At least 777,000 births occur to adolescent girls younger than 15 years in developing countries each year.

Adolescence is the phase of life between childhood and adulthood, from ages 10 to 19. Adolescents have unique physical, social and emotional needs (WHO, 2021f).

Adolescent health is an important sub-field in the fields of Public and Global Health. Given the high numbers of adolescents in low- and middle-income countries especially, adolescent health is a particular Global Health priority.

If you are interested in learning more about adolescent health, follow this link for [optional] readings.

The estimated global adolescent-specific fertility rate has declined by 11.6% over the past 20 years. However when we look at adolescent fertility rates between and within regions and countries, we see significant differences. For example, the adolescent fertility rate in East Asia is 7.1 births per 1,000 women aged 15-19 years. In Central Africa that number jumps to 129.5 births per 1,000 women aged 15-19.

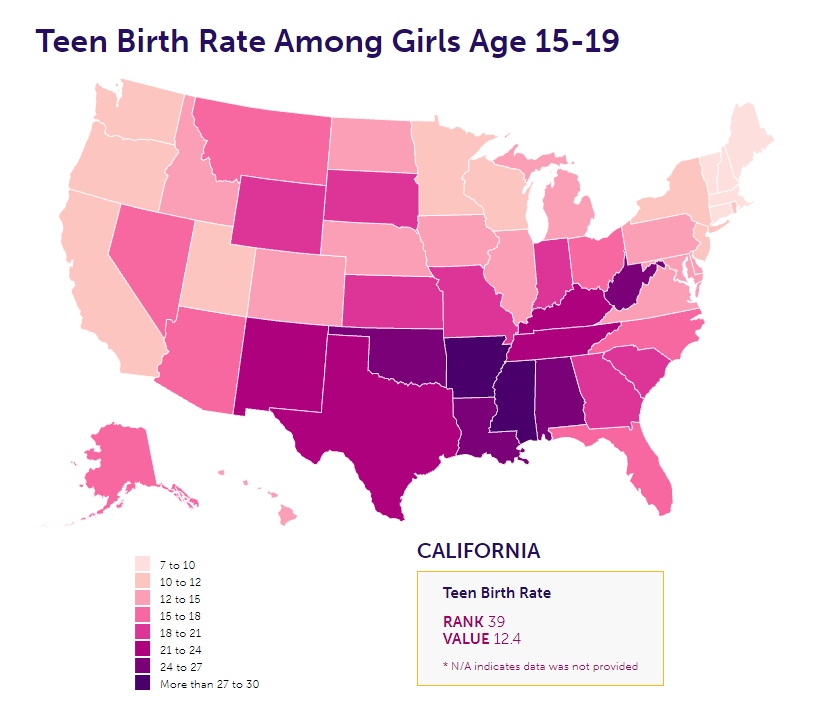

Adolescent pregnancy is a challenge in all regions of the world, not just low- and middle-income countries. Regional differences in adolescent pregnancy rates also exist in high-income contexts.

For example, the national adolescent birth rate among girls in 2019 in the United States was 16.7. However, in Arkansas the rate was 30 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 while in New Hampshire this rate was only 6.6 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 (Power to Decide, 2021).

While the estimated global adolescent fertility rate has declined, the actual number of child births to adolescents has not, due to the large – and in some parts of the world, growing – population of young women in the 15–19 age group. The largest number of adolescent births occur in Eastern Asia (95,153) and Western Africa (70,423).

Causes of Adolescent Pregnancy

Adolescent pregnancies are a global problem occurring in high-, middle-, and low-income countries.

Around the world, however, adolescent pregnancies are more likely to occur in marginalized communities, commonly driven by:

- Poverty

- Lack of education and

- Lack of employment opportunities for girls themselves and their families.

Several factors contribute to adolescent pregnancies and births.

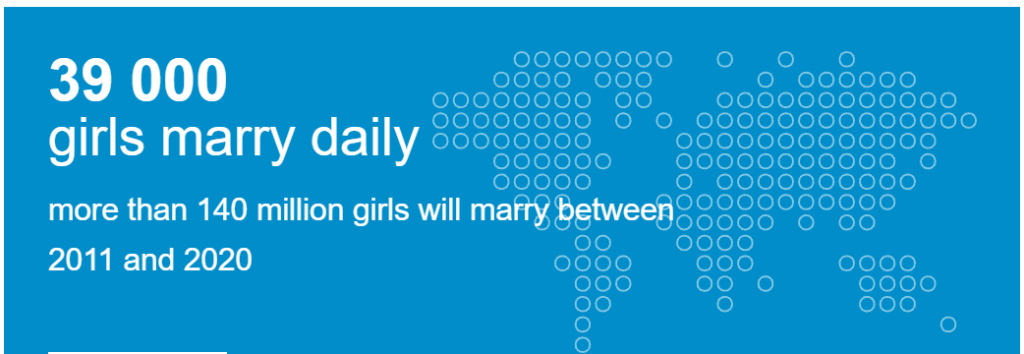

In many societies, girls are under pressure to marry and bear children early.

In least developed countries, at least 39% of girls marry before they are 18 years of age and 12% before the age of 15.

In many places girls choose to become pregnant because they have limited educational and employment prospects. In many socio-cultural contexts, motherhood is valued and marriage or union and childbearing may be the best of the limited options available to young women, girls and their families.

Adolescents who may want to avoid pregnancies may not be able to do so due to knowledge gaps and misconceptions on where to obtain contraceptive methods and how to use them.

Adolescents face barriers to accessing contraception including:

- Restrictive laws and policies regarding provision of contraceptives based on age or marital status

- Health worker bias and/or lack of willingness to acknowledge adolescents’ sexual health needs, and

- Adolescents’ own inability to access contraceptives because of knowledge, transportation and financial constraints

- Unequal gender power dynamics — in some socio-cultural contexts, women and young girls cannot use or obtain contraceptives without the permission of their husband.

- Young girls especially may not be able to negotiate the use of contraceptives with their husbands; they can face harsh repercussions for asking to use contraceptives or for using contraceptives without their husband’s knowledge, including violence and social exclusion.

Early marriage happens in the United States!

[OPTIONAL READING]

Child marriage occurs when one or both of the parties to the marriage are below the age of 18. Child marriage is currently legal in 44 states (only Delaware, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island have set the minimum age at 18 and eliminated all exceptions), and 20 U.S. states do not require any minimum age for marriage, with a parental or judicial waiver. Approximately 248,000 children were married in the U.S. between 2000 and 2010. The vast majority were girls wed to adult men, many much older.

Statutory rape is when one of the parties to sexual activity is below the age of consent. It does not have to be forcible, because a minor is not legally able to consent. 18 U.S.C. Section 2243(a), on the Sexual Abuse of a Minor, applies when a person “knowingly engages in a sexual act with another person” who is between the ages of 12 and 16 and is at least four years younger than the perpetrator. 18 U.S.C. Section 2243(c)(2) allows a defense to this crime when “the persons engaging in the sexual act were at that time married to each other.” This means that, at the federal level, child marriage is viewed as a valid defense to statutory rape.

This law not only suggests that the federal government condones the practice of child marriage, it allows an adult to engage in sexual activity with children as young as 12, and gives sexual predators an incentive to force a child to marry them. The law can effectively turn child marriage into a “get out of jail free” card for predators. This law must be repealed. Repealing 18 U.S.C. § 2243(c)(2) is a simple, commonsense step towards aligning U.S. laws with international standards and discouraging child marriage and rape in the U.S.

(Equality Now, n.d.).

Additionally, adolescents may lack the agency or autonomy to ensure the correct and consistent use of a contraceptive method.

An additional cause of unintended pregnancy is sexual violence, which is widespread with more than a third of girls in some countries reporting that their first sexual encounter was coerced (against their will, without their permission).

Sexual violence is defined as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act,unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work.

Krug et al, 2002

Coercion can cover a whole spectrum of degrees of force. Apart from physical force, it may involve psychological intimidation, blackmail or other threats – for instance, the threat of physical harm, of being dismissed from a job or of not obtaining a job that is sought.

It may also occur when the person aggressed is unable to give consent – for instance, while drunk, drugged, asleep or mentally incapable of understanding the situation. Sexual violence includes rape, defined as physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration – even if slight – of the vulva or anus, using a penis, other body parts or an object.

The attempt to do so is known as attempted rape. Rape of a person by two or more perpetrators is known as gang rape. Sexual violence can include other forms of assault involving a sexual organ, including coerced contact between the mouth and penis, vulva or anus (Krug et al, 2002).

Health Consequences of Adolescent Pregnancy

Early pregnancies among adolescents have major health consequences for adolescent mothers and their babies.

Pregnancy and childbirth complications are the leading cause of death among girls aged 15–19 years globally, with low- and middle-income countries accounting for 99% of global maternal deaths of women aged 15–49 years.

Adolescent mothers aged 10–19 years face higher risks of eclampsia, puerperal endometritis [infection of the uterus] and systemic infections than women aged 20–24 years. Babies born to mothers under 20 years of age face higher risks of low birth weight, preterm delivery and severe neonatal conditions.

Social and Economic Consequences of Adolescent Pregnancy

Social consequences for unmarried pregnant adolescents may include stigma, rejection or violence by partners, parents and peers. Girls who become pregnant before the age of 18 years are more likely to experience violence within a marriage or partnership. Adolescent pregnancy and childbearing often leads girls to drop out of school, which may jeopardize girls’ future education and employment opportunities (WHO, 2020b).

The video clips below detail the risks for, causes of and challenges facing young mothers and parents in two different settings globally: Romania, the Philippines and Nigeria.

Watch at least two of the three following clips. As you watch, what risk factors and causes of high adolescent pregnancy do you learn about in each setting?

Which similarities and differences do you note between the causes and challenges of adolescent pregnancy in the different contexts?

Reflect on the structural and social determinants of health that put young women in different contexts at risk for adolescent pregnancy.

How is becoming pregnant at a young age a social determinant of health in and of itself for young women and girls?

Unsafe abortion

Note: The following section is adapted from WHO: Preventing Unsafe Abortion (2020a).

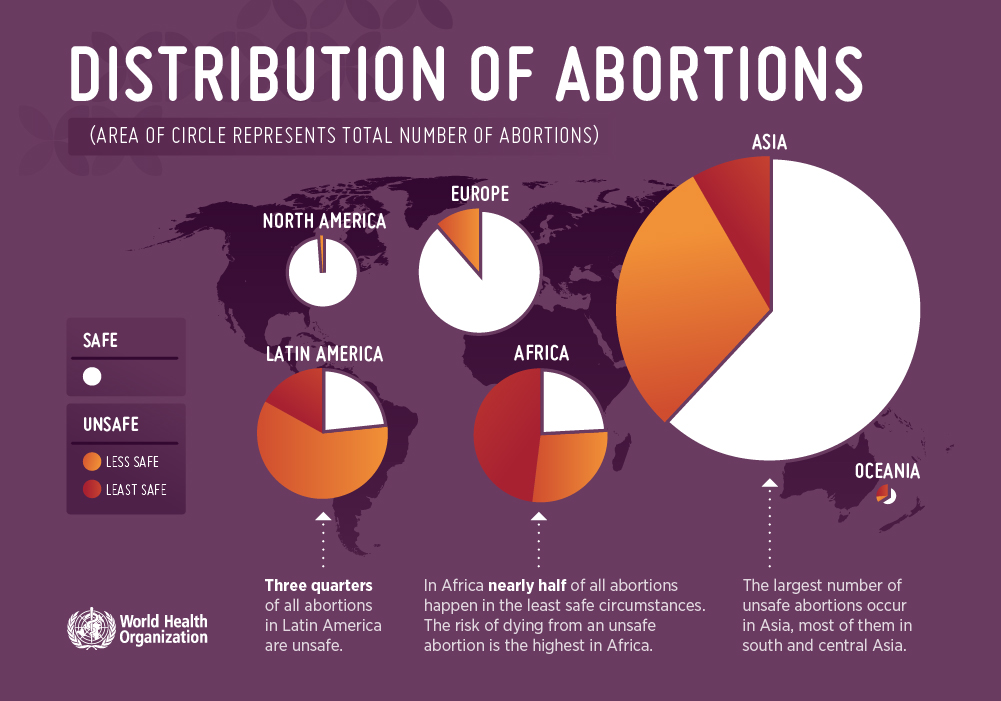

As we learned above, unsafe abortion is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality globally.

Each year between 4.7%-13.2% of maternal deaths can be attributed to unsafe abortion (WHO, 2020a).

As with all causes of maternal mortality, the biggest tragedy of this reality is that these are women’s lives lost unnecessarily.

When completed by a trained provider in sanitary and safe conditions with the appropriation equipment and medication, abortion is one of the safest medical procedures in the world. Mortality rates for safe abortion are less than 1 death per 100,000 procedures performed (Raymond and Grimes, 2012). In the United States, this means that safe abortion is safer for women than childbirth (Raymond and Grimes, 2012). This also means that in 2017 alone, between 14,000-39,000 women’s lives globally could have been saved if they had had access to safe abortion services.

Abortion is a highly politicized issue in a number of countries around the world. In some contexts women and their providers can be criminalized for requesting or performing an abortion, even in the cases of rape or incest. However, even in countries where abortion is illegal or criminalized, individuals with financial means can often find a provider to perform a safe abortion. Systematically marginalized people will have more difficulties obtaining safe abortion. This disparity in access to safe abortion is a health inequity.

In other countries — such as almost all European countries, China, Nepal and Ethiopia to name just a few — access to safe abortion services is considered health care and a human right. In many countries, anyone can obtain a safe abortion for free from the government on demand.

Abortions are safe when they are carried out with a method that is recommended by WHO and that is appropriate to the pregnancy duration, and when the person carrying out the abortion has the necessary skills. Such abortions can be done using tablets (medical abortion) or a simple outpatient surgical procedure.

WHO, 2020a

An abortion is unsafe when it is carried out either by a person lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both. The people, skills, and medical standards considered safe in the provision of induced abortions are different for medical abortion (which is performed with drugs alone), and surgical abortion (which is performed with a manual or electric aspirator). Skills and medical standards required for safe abortion also vary depending upon the duration of the pregnancy and evolving scientific advances.

WHO, 2020a

Between 2015-2019, it is estimated that 73.3 million abortions (safe and unsafe) occurred worldwide each year.

Estimates from 2010-2014 showed that around 45% of all abortions were unsafe.

Almost all of these unsafe abortions took place in developing countries. Estimates from 2012 indicate that in developing countries alone, an estimated 7 million women per year were treated in hospital facilities for complications of unsafe abortion.

Unsafe abortion can include procedures carried out by untrained/ non-medically trained or licensed individuals and procedures in unsanitary conditions without appropriate medication including anesthesia and anti-biotics. Unsafe procedures can include ingesting dangerous substances or herbs and insertion of foreign bodies into the vagina and uterus.

Women, including adolescents, with unwanted pregnancies often resort to unsafe abortion when they cannot access safe abortion.

Barriers to accessing safe abortion include:

- Restrictive laws

- Poor availability of services

- High cost

- Stigma

- Health providers’ refusal to perform abortion if abortion goes against their personal beliefs or is against the law in their country of practice

- Unnecessary legal or health system requirements, such as mandatory waiting periods, mandatory counselling, provision of misleading information, third-party authorization, and medically unnecessary tests that delay care.

Who is at risk for unsafe abortion?

Any woman with an unwanted pregnancy who cannot access safe abortion is at risk of unsafe abortion. Women living in low-income countries and poor women are more likely to have an unsafe abortion. Deaths and injuries are higher when unsafe abortion is performed later in pregnancy. The rate of unsafe abortions is higher where access to effective contraception and safe abortion is limited or unavailable.

Complications of unsafe abortion requiring emergency care

Following unsafe abortion, women may experience a range of harms that affect their quality of life and well-being, with some women experiencing life-threatening complications. The major life-threatening complications resulting from the least safe abortions are haemorrhage, infection, and injury to the genital tract and internal organs.

Access to treatment for abortion complications

Health-care providers are obligated to provide life-saving medical care to any woman who suffers abortion-related complications, including treatment of complications from unsafe abortion, regardless of the legal grounds for abortion. However, in some cases, treatment of abortion complications is administered only on the condition that the woman provides information about the person(s) who performed the illegal abortion.

The practice of extracting confessions from women seeking emergency medical care as a result of illegal abortion puts women’s lives at risk. The legal requirement for doctors and other health-care personnel to report cases of women who have undergone abortion, delays care and increases the risks to women’s health and lives. UN human rights standards call on countries to provide immediate and unconditional treatment to anyone seeking emergency medical care.

Prevention and control

Unsafe abortion can be prevented through:

- Comprehensive sexuality education;

- Prevention of unintended pregnancy through use of effective contraception, including emergency contraception; and

- Provision of safe, legal abortion.

Optional but highly recommended video from MSF Doctor on experiences in the field with unsafe abortion:

In addition, deaths and disability from unsafe abortion can be reduced through the timely provision of emergency treatment of complications or post abortion care (PAC).

Post abortion care (PAC) consists of emergency treatment for complications related to spontaneous or induced aboritson, family planning and birth spacing counseling, and provision of family planning methods for the prevention of further mistimed or unplanned pregnancies that may resutl in repeat induced abortions (Postabortion Care, n.d.).

In countries where medical abortion is illegal or criminalized, health providers are allowed to offer PAC to women but not abortion services. Therefore, if a woman comes to a clinic having attempted an abortion that is unsuccessful — the fetus is still viable — then health providers are left with difficult decisions. They can face fines, jail time and revoking of their medical licenses if they are thought to be providing abortion services.

Female Genital Cutting (FGC)

Note: Parts of this section adapted from WHO: Female Genital Mutilation (2020c) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation; other resources as noted.

Female genital cutting (FGC) – also referred to as female genital mutilation (FGM) – is one of the most highly charged Women’s Health topics in the field of Global Health.

Female genital cutting (FGC) — also referred to as female genital mutilation (FGM) — involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

WHO, 2020c

A note on FGC in the field of Global Health:

Engaging in conversations around FGC from a decolonized perspective

FGC/M is a contemporary Global Health topic which, more than many Global Health topics, demands that we return to the concepts we explored in Section 3.14: Understanding the Role of Culture in Health.

As you read the following section, keep in mind the discussions we had about ethnocentrism, cultural relativism, cultural humility and cultural competence and the importance of these concepts in understanding and engaging with health practices which you yourself might not be familiar with, practice or fully understand.

The authors of this text are not advocating for or endorsing the practice of FGC, especially on young girls and women who have no choice if they undergo the procedure or not.

What we are encouraging in relation to FGC as a Global Health issue is:

- A complete understanding of the reasons why this procedure is performed in particular cultural groups

- The socio-cultural significance of this procedure

- Colonial histories and western representations of this procedure

- The fact that some women and girls choose to undergo this procedure

- An approach to eradicating this procedure that is effective, rather than forcing the practice to go underground and, therefore, be potentially more harmful to women and girls.

Students are encouraged to reflect on the ways in which western authorities and NGOs have framed and responded to the practice of FGC. We fully condemn violations of women’s and girls’ human rights and any risk to women’s and girls’ health. It is also important to understand the practice of FGC and the international response to this practice in the context of colonial histories and power dynamics between (white, western) colonizers and colonizers’ representation of ‘others.’

As students of Global Health, we can condemn violations of women’s and girls’ human rights while also understanding the importance of considering why individuals engage in and continue this practice. We can also question how the practice has been and continues to be represented in western discourse and media from colonial times until today — and what ‘story’ these representations of largely African practices by western individuals continue to tell about ‘others’ from a western perspective.

An international response to this practice which will improve the rights and health of women and girls requires a deep understanding of the practice itself, the reasons why it continues today and the arguments for continuing the practice given by those who view FGC as an important cultural practice.

Some optional further reading on decolonizing research and the narrative around FGC can be found in a call out box at the end of this section.

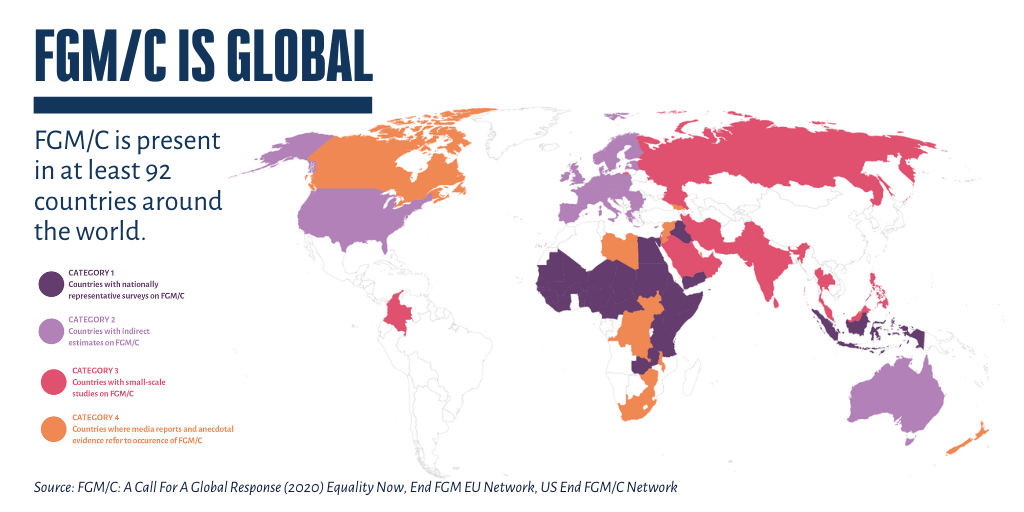

FGC is mostly carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15, though it can sometimes be carried out on adult women. More than 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone some form of FGC in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where the practice is concentrated.

Traditional circumcisers usually perform this procedure on women and girls. Traditional circumcisers also often play other central roles in communities such as attending childbirths. In many settings, health care providers perform FGC/M due to the belief that the procedure is safer when medicalized. This is referred to as the medicalization of FGC. The World Health Organization is opposed to health care providers performing FGC.

The medicalization of female genital cutting refers to situations in which FGC is practiced by any category of health provider, whether in a public or private clinic, at home or elsewhere.

UNFPA, 2018

FGC is classified into 4 major types.

Type 1: this is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals), and/or the prepuce/ clitoral hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans).

Type 2: this is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without removal of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva ).

Type 3: Also known as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoral prepuce/clitoral hood and glans (Type I FGM).

Type 4: This includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

De-infibulation refers to the practice of cutting open the sealed vaginal opening of a woman who has been infibulated, which is often necessary for improving health and well-being as well as to allow intercourse or to facilitate childbirth (WHO, 2020c).

While you can see from the image below that ethnic and cultural groups which practice FGC are mostly located on the continent of Africa, the practice also takes place in other regions of the world including high-income countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and countries across Europe.

Immediate complications from this procedure can include:

- Severe pain

- Excessive bleeding (haemorrhage)

- Genital tissue swelling

- Fever

- Infections e.g., tetanus

- Urinary problems

- Wound healing problems

- Injury to surrounding genital tissue

- Shock

- Death.

Long-term complications can include:

- Urinary problems (painful urination, urinary tract infections);

- Vaginal problems (discharge, itching, bacterial vaginosis and other infections);

- Menstrual problems (painful menstruations, difficulty in passing menstrual blood, etc.);

- Scar tissue and keloid;

- Sexual problems (pain during intercourse, decreased satisfaction, etc.);

- Increased risk of childbirth complications (difficult delivery, excessive bleeding, caesarean section, need to resuscitate the baby, etc.) and newborn deaths;

- Need for later surgeries: for example, the sealing or narrowing of the vaginal opening (Type 3) may lead to the practice of cutting open the sealed vagina later to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth (deinfibulation). Sometimes genital tissue is stitched again several times, including after childbirth, hence the woman goes through repeated opening and closing procedures, further increasing both immediate and long-term risks;

- Psychological problems (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, etc.).

The reasons why female genital cuttings are performed vary from one region to another as well as over time, and include a mix of sociocultural factors within families and communities.

The most commonly cited reasons for performing FGC are:

- Where FGC is a social norm, the social pressure to conform to what others do and have been doing, as well as the need to be accepted socially and the fear of being rejected by the community, are strong motivations to perpetuate the practice. In some communities, FGC is almost universally performed and unquestioned.

- FGC is often considered a necessary part of raising a girl, and a way to prepare her for adulthood and marriage.

- FGC is often motivated by beliefs about what is considered acceptable sexual behaviour. It aims to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity. FGC is in many communities believed to reduce a woman’s libido and therefore believed to help her resist extramarital sexual acts. When a vaginal opening is covered or narrowed (Type 3), the fear of the pain of opening it, and the fear that this will be found out, is expected to further discourage extramarital sexual intercourse among women with this type of FGC.

- Where it is believed that being cut increases marriageability, FGC is more likely to be carried out.

- FGC is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are clean and beautiful after removal of body parts that are considered unclean, unfeminine or male.

- Though no religious scripts prescribe the practice, practitioners often believe the practice has religious support.

- Religious leaders take varying positions with regard to FGC: some promote it, some consider it irrelevant to religion, and others contribute to its elimination.

- Local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice. Likewise, when informed, they can be effective advocates for abandonment of FGC.

- In most societies, where FGC is practised, it is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation.

- In some societies, recent adoption of the practice is linked to copying the traditions of neighbouring groups. Sometimes it has started as part of a wider religious or traditional revival movement.

Critiquing the international representation of and response to FGC: a fight that is making it worse?

In this section of reading, think back to our conversations about the representation of ‘other’ cultures and contexts by western countries and institutions.

As noted above, in discussing FGC in this way we are not as authors and scholars endorsing or advocating for the continuation of FGC. However, we are asking students to look critically at the international response to FGC. Ask yourself:

- How is the framing of FGC by the international community representing ‘other’ cultures?

- How is this representation rooted in colonialism, racism and the colonial view of ‘others’ as less than colonizing countries?

- Is the international community’s framing and fight against FGC actually working to end the practice and improve the rights, health and safety of women and girls around the world?

Since the 1990s, actors from across the international community have condemned the practice of FGC as ‘wrong’ and a violation of human rights. These actors include international NGOs, the United Nations, the WHO and governments and have campaigned to end the practice of FGC through education and laws which criminalize the practice.

However, though recent data shows that in many contexts fewer younger women are undergoing FGC than in previous generations, FGC is still prevalent in many countries throughout the world and is a practice increasing in prevalence in countries such as the United States, Canada and European nations.

There is a growing body of literature from scholars and activists in contexts where FGC is practiced and from the west which questions the effectiveness of criminalizing FGC/M and the risks of condemning the practice without understanding its deeper histories, its cultural significance and the power dynamics surrounding the debate.

This group of scholars and activists believes that “the existing narrative on FGC has been punitive and indifferent to the historical and cultural processes that construct and inform the practice” and relies on colonial representations of ‘other’ cultures as “primitive”, “savage” and opposed to human rights (Werunga, Reimer-Kirkham and Ewashen, 2016; Sanogo and Pusumane, 2021).

Most importantly, despite years of strong campaigning against the practice, there is evidence that this approach to stopping FGC is actually making the practice continue underground or by medical providers (Seleina Parsitau, 2018). If parents or health professionals who perform the procedure are afraid to seek health services for their daughters if they have health complications from the procedure, laws that criminalize FGC could actually put women and girls at greater risk of long-term complications and death from the practice.

Excerpts from A Decolonizing Methodology for Health Research on Female Genital Cutting

(Werunga, Riemer-Krikham and Washen, 2016)

The topic of female genital cutting (FGC) remains contentious as reflected by decades of debates and discourses regarding the practice. While the practice itself predates religion, the framing of the FGC problematic had its roots in European colonization and the civilizing mission of the colonizers.

In other words, the objectionableness of this centuries-old tradition is a direct result of the clash of cultures engendered by the colonial process. In the case of FGC, European colonizers frowned upon a practice that they deemed barbaric and harmful and set out to denounce it. This denunciation paved the way for modern-day

anti-FGC discourse along with the associated polarity. …

The FGC issue is further complicated by modern immigration and migratory trends, as the practice is no longer confined to countries where it was historically practiced. Western countries are now faced with increasing numbers of women and girls who have been cut, and with the very real possibility that women and girls are being cut within Western borders. The nature of FGC as a gendered and embodied practice has led to multidisciplinary and multitheoretical approaches to situate it within analyses of power, patriarchy, feminism, location, economics, and religion. The enduring undertones, regardless of disciplinary or theoretical approach, perpetrate a view of FGC as oppressive and as a victimization of girls and women by an uncompromising

patriarchal cultural machine.

It is worth noting that despite fervent eradication endeavors stemming mostly from the Global North,* and despite the criminalization of FGC and its subsequent labeling by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a violation of women’s human rights, this practice still endures and remains contentious.

Scholars have sought to offer an understanding of FGC from various conceptual standpoints, including cultural relativist, feminist, humanist, and moral analyses. In this article, while acknowledging the contributions of multiple theoretical models, we recognize that a conceptual gap still exists, particularly in how to frame the FGC narrative to allow for a more nuanced and complete response by health care providers and policy makers in host† countries.

The issue of framing is apparent in the controversy that exists over what to name the practice, with opponents referring to it as “mutilation” and others opting for “circumcision,” “surgery,” or, as in our case, the more neutral “cutting.” Some scholars have argued that the resistance encountered by some anti-FGC opponents in their eradication endeavors can be partially attributed to the “mutilation” label, which some practicing communities find offensive.

Western constructions of FGC fail to account for historical processes that continue to not only alienate and mark women but also impinge on their ability to access health care services in host countries. Much of the anti-FGC narrative as propagated by organizations such as Equality Now and the WHO has tended to focus on the perceived effects, often traumatic and/or sexual, to the exclusion of the historical, social, cultural, and economic reasons for FGC. A complex topic such as FGC requires a well-thought-out, multifactorial approach. Such an approach cannot preclude an African standpoint, or indeed a historical analysis of the practice, if it is to offer a way forward while accounting for potential colonizing effects.

…

FGC is a complex topic that can only be understood within the historical contexts of communities and cultures that practice it. This complexity is further compounded when FGC is viewed in the context of migration and within the borders of Western hegemonic cultures that have historically marked FGC as a harmful and undesirable cultural practice.

For decades, there have been sustained efforts by anti-FGC organizations and global bodies such as the WHO to try and eradicate FGC with a punitive narrative mostly centered on the trauma and human rights violation view of FGC. In this article, we have offered an alternative narrative, a decolonizing methodology, by framing the FGC issue within critical theoretical perspectives in recognition of the complexities and deeply contextual situatedness of FGC for affected women as well as for practicing communities.

A postcolonial feminist framing of FGC along with an African contextual understanding offers a more nuanced understanding of the situated structure and domain of individual experiences as well as the effects of the always-present power differentials effected by Western hegemonic practices.

An intersectional analysis has policy and practice implications, as it allows for critical consciousness not just for researchers but also for nursing and other health care providers along with stakeholders in host nations particularly in identifying social determinants of health and the provision of safe, accessible, and equitable health care for all. Critical perspectives allow for this kind of reflection and analysis, opening new spaces for women’s agency and voice. A decolonizing methodology is needed to counter the often-repeated single story and to present alternate stories.

Only then will it be possible to address FGC.

It is undebatable that there is no medical justification for this procedure and the procedure puts young girls and women at risk for a number of physical health complications, including death, as well as emotional and psychological trauma. We can accept this and agree that women and girls should not be hurt or die from avoidable causes.

As Global Health actors we can also, however, recognize the importance of understanding the socio-cultural context of this practice in order to better address it. This includes further decolonizing narratives and representations of ‘other’ cultures by westerners from colonial times through the present day.

We unfortunately do not have enough time in this course to fully work our way through this important conversation. However, you are highly encouraged to read the optional resources listed below if you want to engage further in this dialogue and international debate.

The first video clip below offers different perspectives from individuals within a community that practices FGC.

The second video is an example of the ways in which the international community has framed FGC. It is informative about the prevalence of the practice, however we encourage students to think about how this framing of FGC represents the cultures that continue to practice FGC. How are women and girls who undergo the practice represented? And who is doing the storytelling here?

The authors of this text also want to note that they do not support the title of this second video — The Truth about Female Genital Mutilation — as it suggests that there is one ‘true truth’ about this topic and leaves little room for discussion or contextualization. In addition, as discussed above as well, the labeling of this practice as ‘mutilation’ communicates a particular message about this practice and the women and girls who have undergone it.

One takeaway message from this reading should be that there is no one ‘truth’ about FGC/M; there are many perspectives to consider in this conversation about the practice in order to address it in a way that actually advocates for the rights, health and safety of the women and girls who live in contexts where the practice is prevalent.

As Sanogo and Pusumane wrote: “The main question is how do we establish an ethical space of listening and what do we do with marginalised voices of women who are demonized for believing in [FGC]?” (2021).

As Global Health actors we can both recognize the potential and very serious harm, including death, this practice can cause to women and girls, while also understanding how the western framing of FGC since colonial times has and continues to represent (mostly) African cultures in particular ways that justified and continue to justify the west ‘fixing’ Africa.

[Optional] Highly recommended reading on FGC:

Why Some Women Choose to Get Circumcised

Female Circumcision is More Complicated Than You Think

[Optional] Further reading on FGC:

A Call for The Epistemic Fluidity of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

A Decolonizing Methodology for Health Research on Female… : Advances in Nursing Science (UIC students – available via the UIC library database)

Violence against women

Note: The following section adapted from WHO: Violence against women (2021g). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

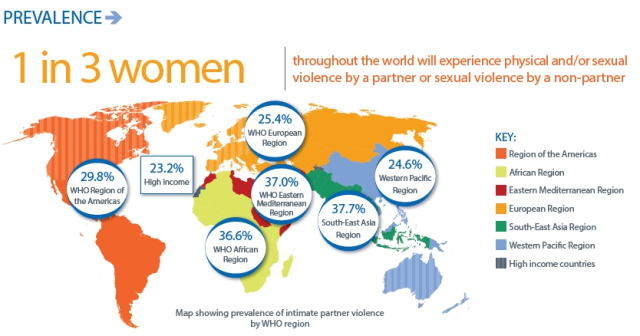

WHO estimates that globally about 1 in 3 — or 30% of women — worldwide have been subjected to either physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. Think about that for a moment: there is a good chance that for every 3 women you know, at least 1 of them has experienced or will experience violence in their lifetime.

Violence against women is a major Public and Global Health problem, prevalent in all countries around the world, and is a violation of women’s human rights.

The United Nations defines violence against women as any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

WHO, 2021g

Intimate partner violence refers to behaviour by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours.

WHO, 2021g

Sexual violence is “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting. It includes rape, defined as the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus with a penis, other body part or object, attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching and other non-contact forms.”

WHO, 2021g

Over a quarter of women aged 15-49 years who have been in a relationship have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner at least once in their lifetime (since age 15).

As the graphic below demonstrates, violence against women is not a human rights violation that is limited to particular regions, countries or incomes — violence against women is a Global Health challenge.

Globally as many as 38% of all murders of women are committed by intimate partners. In addition to intimate partner violence, globally 6% of women report having been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner, although data for non-partner sexual violence are more limited.

While intimate partner and sexual violence can be perpetrated by women or men, intimate partner and sexual violence are mostly perpetrated by men against women.

Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence

Lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic and its social and economic impacts have increased the exposure of women to abusive partners and known risk factors, while limiting their access to services. Situations of humanitarian crises and displacement may exacerbate existing violence, such as by intimate partners, as well as non-partner sexual violence, and may also lead to new forms of violence against women.

Intimate partner and sexual violence is the result of factors occurring at individual, family, community and wider society levels that interact with each other to increase or reduce risk (protective). Some are associated with being a perpetrator of violence, some are associated with experiencing violence and some are associated with both.

Risk factors for both intimate partner and sexual violence include:

- lower levels of education (perpetration of sexual violence and experience of sexual violence);

- a history of exposure to child maltreatment (perpetration and experience);

- witnessing family violence (perpetration and experience);

- antisocial personality disorder (perpetration);

- harmful use of alcohol (perpetration and experience);

- harmful masculine behaviours, including having multiple partners or attitudes that condone violence (perpetration);

- community norms that privilege or ascribe higher status to men and lower status to women;

- low levels of women’s access to paid employment; and

- low level of gender equality (discriminatory laws, etc.).

Factors specifically associated with intimate partner violence include:

- past history of exposure to violence;

- marital discord and dissatisfaction;

- difficulties in communicating between partners; and

- male controlling behaviours towards their partners.

- Factors specifically associated with sexual violence perpetration include:

- beliefs in family honour and sexual purity;

- ideologies of male sexual entitlement; and

- weak legal sanctions for sexual violence.

- Gender inequality and norms on the acceptability of violence against women are a root cause of violence against women.

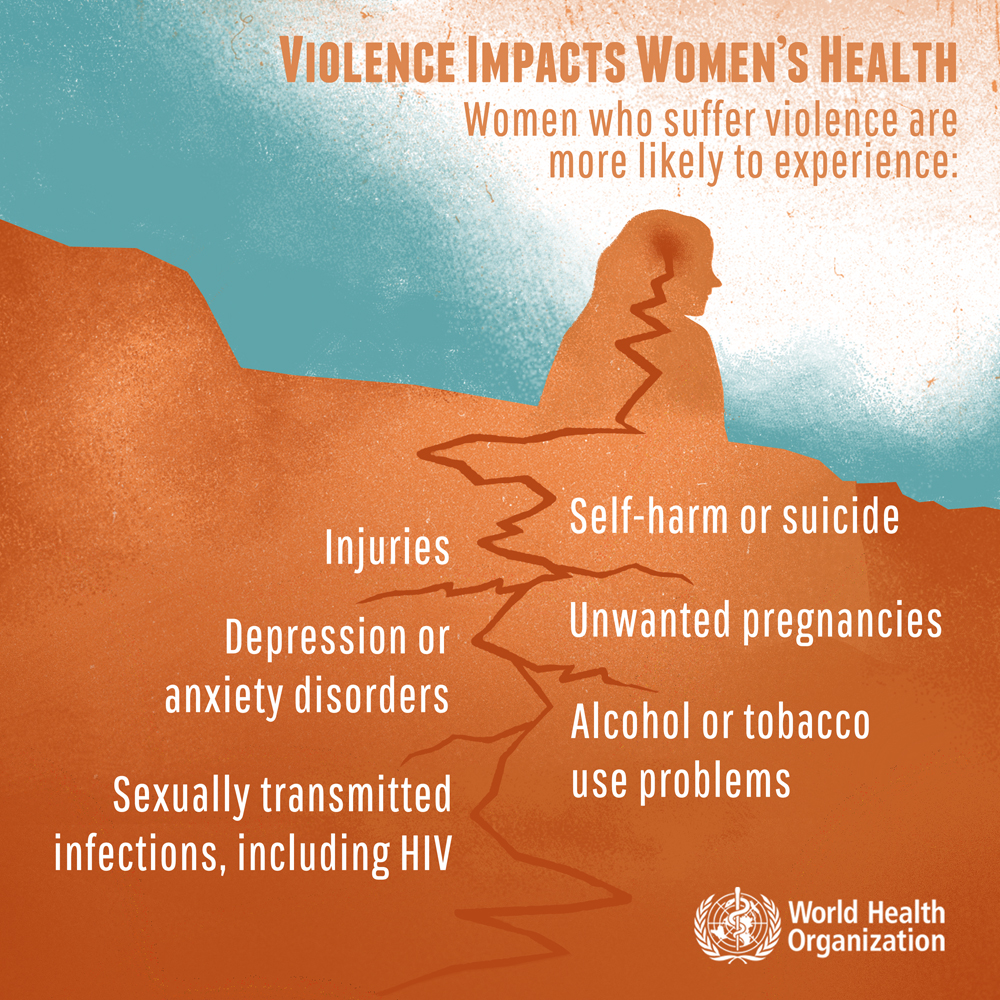

Health Consequences for Women

Intimate partner (physical, sexual and psychological) and sexual violence cause serious short- and long-term physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health problems for women. They also affect their children’s health and wellbeing. This violence leads to high social and economic costs for women, their families and societies.

Such violence can:

- Have fatal outcomes like homicide or suicide.

- Lead to injuries, with 42% of women who experience intimate partner violence reporting an injury as a consequence of this violence.

- Lead to unintended pregnancies, induced abortions, gynaecological problems, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

- Intimate partner violence in pregnancy also increases the likelihood of miscarriage, stillbirth, pre-term delivery and low birth weight babies.

WHO’s 2013 study on the health burden associated with violence against women found that women who had been physically or sexually abused were 1.5 times more likely to have a sexually transmitted infection and, in some regions, HIV, compared to women who had not experienced partner violence. They are also twice as likely to have an abortion. The same 2013 study showed that women who experienced intimate partner violence were 16% more likely to suffer a miscarriage and 41% more likely to have a pre-term birth.

(WHO, 2021g)

These forms of violence can lead to depression, post-traumatic stress and other anxiety disorders, sleep difficulties, eating disorders, and suicide attempts.

Health effects can also include:

- headaches

- pain syndromes (back pain, abdominal pain, chronic pelvic pain)

- gastrointestinal disorders

- limited mobility and

- poor overall health.

Sexual violence, particularly during childhood, can lead to:

- increased smoking

- substance use, and

- risky sexual behaviours.

It is also associated with perpetration of violence (for males) and being a victim of violence (for females).

Further impacts: social and economic costs including costs to children

Children who grow up in families where there is violence may suffer a range of behavioural and emotional disturbances. These can also be associated with perpetrating or experiencing violence later in life.