2. Key Concepts

- Culture

- Intersectionality

- Positionality

- Traditional medicine

- Western biomedicine

- Patterns of resort

- Cultural relativism

- Ethnocentrism

- Interconnectedness of culture and health

- Cultural diversity

- Cultural competency

- Cultural humility

- Culturally safe care

- Multiculturalism in health

- Culture of health

3. Prelim Engagement

1. Exploring and understanding where and how Culture and Health intersect is some of the most important work of Public and Global Health actors. Aside from the importance of these conversations and analyses for the fields of Public and Global Health on the population level, understanding the intersections of Culture and Health is also very personal. Whether we recognized it or not, we have all experienced the intersection of Culture and Health, including cultural challenges, in our own health and health care seeking. Yet, most of us have not reflected on why culture matters in health, how the two interact, how they interconnect and what the outcomes from these interactions may be.

Intersections of Culture and Health are so fundamental to Public and, especially, Global Health work because Culture influences our concepts, beliefs, perspectives, decisions and choices that are important for our health and daily living. These intersections and interactions happen at both individual and community levels, and affect our assumptions and health behavior as individuals but also our assumptions and work as Public and Global Health professionals.

The concepts of Culture and Health shape a challenging, multi-faceted ecosystem within the broader context of Public Health, which involves a number of key actors including as local communities, populations, health providers , policy makers, decision makers, educators, researchers and many others. Isn’t it so interesting to think that something as personal as cultural beliefs and practices --- including foods, religion, holidays, beliefs, ancestry, stories, music, art and other aspects of culture --- can actually affect how we think about health and the health choices we make? ,

As you watch the following videos to get you acquainted with the interactive and mutually influential roles of Culture and Health, reflect on personal experiences, stories you have heard from family and friends, or cases you have read in the news where Culture intersected with Health. Try to recognize challenges stemming from the intersection of Culture and Health and reflect on the importance of getting a deeper understanding of these two concepts. What is the importance of these reflections and analyses? How can we apply these reflections in health care, Public and Global Health contexts to improve health outcomes?

2. In the following video about Cultural Competence and Health, the narrator references the concept of health literacy. We discussed this concept in the context of the social determinants of health (Section 1.4: Defining the Determinants of Health). As a reminder, health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” (CDC, 2021). In Section 1.4, we explored how education, as a SDOH, could increase an individual’s health literacy. As you watch this short video, reflect on how culture and cultural beliefs might also have an effect or influence an individual’s health literacy.

3. In this final video, reflect on how considering Culture in health care and the fields of Public and Global Health is especially important when working with populations and individuals which have experienced and continue to experience systematic discrimination. The example explored in the video below highlights experiences of Indigenous (Aboriginal) people living in Canada and the local health authorities’ attempts to make health care accessible and culturally safe for populations which have, as we will explore in more detail in an upcoming section, experienced brutal and unjust forms of Cultural erasure by colonizing governments.

How can you relate the experiences, themes and interventions explored in this video to structural and social determinants of health we have discussed throughout this course? How is Culture --- and the level of consideration of Culture in health care, Public and Global Health --- a structural and social determinant of health?

What is Culture?

When you think of the word culture, what words come to mind? Do you think of any personal experiences, like your own family traditions or practices from places you have traveled to that were new to you?

When you think of culture, do you think of food?

Music?

Family?

Holidays?

Traditions?

Art?

Ways to heal if you are sick?

Can you define culture by any one thing?

Most people find it hard to define culture in one word, concept or experience. Culture encompasses many things and influences our choices as individuals, households and populations in many ways.

Culture can be defined as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group … that encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs.

(UNESCO, 2009)

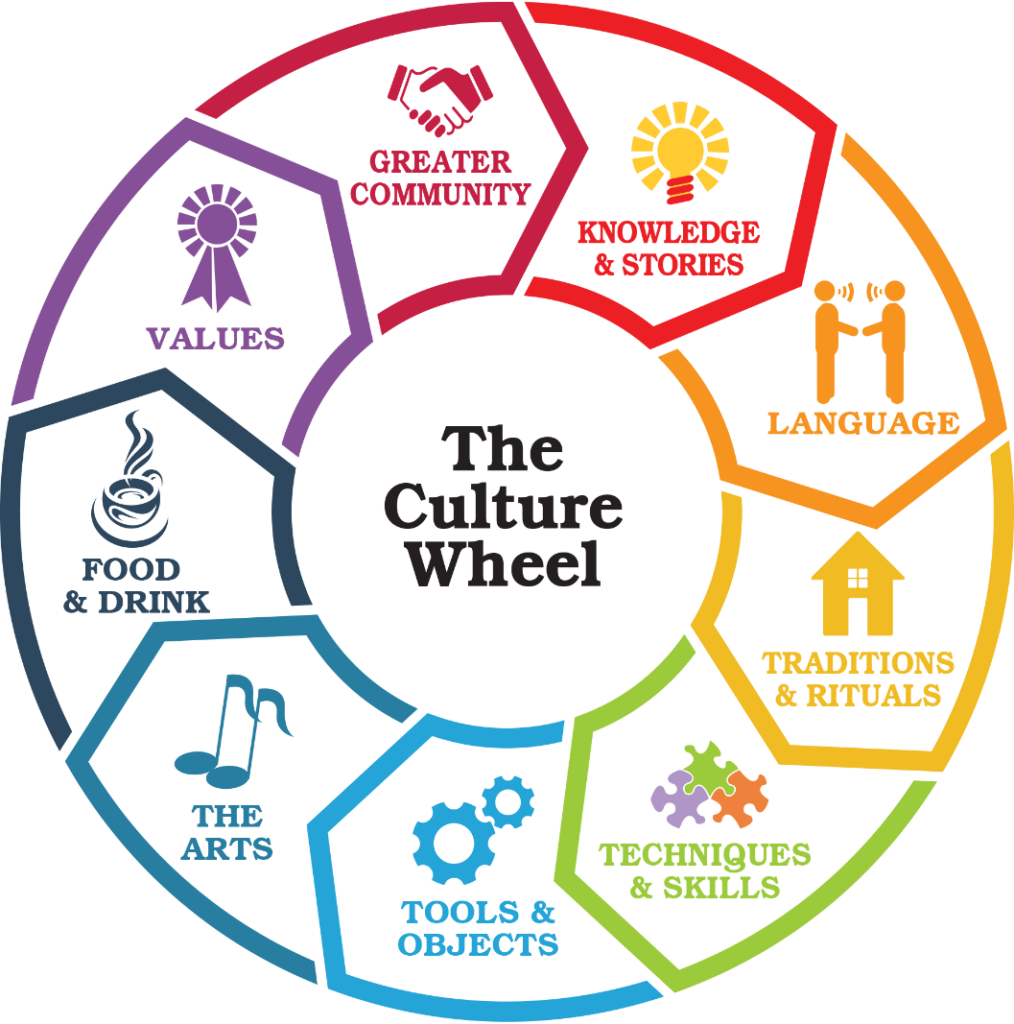

As the graphic below illustrates, culture is a multifaceted, intersectional concept that each of us will understand, define and experience differently.

Let’s explore the role of Culture in health!

In 2014 the Lancet Commission on Culture and Health, argued that “the systematic neglect of culture in health and health care is the single biggest barrier to the advancement of the highest standard of health worldwide.”

Can you think of a way that culture plays a role in your health, including the ways you define and seek out healing and healthcare?

For example, imagine you wake up with a cold — what do you do? Do you eat certain foods? Do you prepare a special drink? Is the drink hot or cold? Do you avoid specific foods or activities? Maybe you make a doctor’s appointment right away, or maybe you call your acupuncturist, chiropractor — or a family member for advice.

Where did you learn these healing practices? From your family? From your ‘culture’? Or have you learned or borrowed any practices from other cultural traditions or belief systems?

Now let’s think about health providers — sure, we can assume that health providers like doctors, nurses and other medical professionals are trained with much of the same medical knowledge. But aren’t doctors and nurses people with a particular culture too? How might the culture of different providers affect the care they give generally — or to specific people?

Understanding how culture influences and informs individuals’ perceptions of health, their health behaviors, their health needs and health outcomes is an essential part of being a public and global health actor.

Cultural beliefs, traditions and practices can affect individuals’ and populations’ health behaviors. If health systems or providers do not integrate a meaningful understanding of culture into their practice and delivery of health services, some individuals or populations might choose to delay care seeking. Or, some might not seek care at all. These delays – or avoiding – care seeking can have serious negative consequences on health outcomes.

Watch the following video to explore some more of the practical applications of Cultural considerations within a health context — and the potential consequences of not considering Culture in medicine, Public and Global Health.

Patterns of Resort

When a family member is sick, why do some people choose to visit a traditional healer before a doctor trained in western biomedicine? Why do others trust practitioners trained in traditional practices to treat a headache but not diseases like cancer?

Patterns of resort refers to the steps individuals or families take to address ill health, including the types of practitioners they use and the timing of their care seeking

(Skolnik, 2019)

Patterns of resort is often used today to mean that people try the most familiar, simplest or cheapest treatments [for illness] first and seek more expensive, complex or unfamiliar treatments later.

(Barnard Health Care, 2020)

A number of individual and social determinants influence individuals’ choices to seek health care from different types of practitioners. These determinants can include, but are not limited to:

- Cultural traditions and beliefs around illness, disease and appropriate treatments for each

- Trust, or lack of trust, of different medical providers and practitioners

- Gender preference for a provider

- Language spoken by the patient and health providers

- Cost of services

- Forms of payment accepted (does the provider only accept cash? Insurance? Does the provider accept alternative forms of payment, like animals or food or payment in installments?)

- Physical access to different services (ie distance to facility, availability of transportation)

- Indirect costs of services (ie lost wages/ inability to take time off of work, child care costs, transport costs, etc)

Certain illnesses might only be believed to respond or have only responded to certain kinds of treatment; a spiritual illness, for example, might only respond to treatment by a spiritual or religious healer and not the treatment of a western biomedical provider. A woman might only want to see a woman health provider and the only biomedical provider nearest to her is a man; or, socio-cultural norms might prohibit female patients from being treated by male doctors. In some contexts, traditional healers might communicate with patients in local language dialects while nurses and doctors in biomedical health facilities may not.

Western biomedicine is a system in which medical doctors and other healthcare professionals treat symptoms and diseases using drugs, radiation, or surgery. [Western biomedicine] is also [referred to as] allopathic medicine, biomedicine, conventional medicine, mainstream medicine and orthodox medicine.

(National Cancer Institute, n.d.)

Traditional medicine is the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness.

(WHO, 2019)

The following videos offer examples of how different traditional medicine practices are used by populations around the world to maintain good health and combat illness and disease — including in high income countries. We suggest you choose at least one to watch, though all are interesting!

Note how traditional medicine is used around the world either on its own as preventive or curative health care or in parallel with western biomedical diagnoses and treatments.

Where traditional medicine is widely practiced, traditional medicine may cost less money than biomedical services. A family with limited financial resources might take a sick child to a traditional healer first and only go to a western biomedical provider if the child does not get well. Or, as integrated members of the community, traditional healers may accept payment in installments or forms of payment other than cash such as food, animals or barter services. Sometimes traditional healers are the only healers physically accessible to populations if biomedical health services are located very far away and transportation is not available or is too expensive

In countries like the United States, however, medical practices such as acupuncture which are not covered by most health insurance providers might actually be more expensive than visiting a western biomedical doctor and could be considered a ‘luxury’ medical treatment.

These hypothetical examples all illustrate different factors in different contexts which affect patterns of resort in healthcare seeking.

While you watch these videos, reflect on the reasons people give for using traditional medicine or western medicine (in Nigeria and other former British colonies referred to sometimes as ‘English medicine’)?

How do these different factors affect peoples’ patterns of resort in healthcare seeking?

Working Across Cultures

One of the most intriguing and exciting aspects of work in global health can be the opportunity to engage with and learn about cultural contexts and practices which are very different from your own. This ‘culture contact’ can happen even when working in your own country or own community.

To ground our discussion about working across cultures in Public and Global Health, watch this short video about a Nigerian bonesetter, who practices traditional medicine. Pay close attention to your initial reactions to the information shared in this video.

What did you think about the traditional bone setter from Nigeria who uses herbs to heal fractured bones?

Were these practices familiar or different from your own perceptions of ‘medical care’? Did you find yourself judging them? If you broke a bone, would you go to a bonesetter? Can singing, prayers and animal sacrifices treat illness or disease?

Is a health treatment ‘wrong’ just because it is not familiar to us? To protect the safety and well-being of all individuals, what policies need to be in place within countries to regulate the practice of western biomedical and traditional medicines?

What ‘lens’ do you use when you consider cultural practices, beliefs and norms very different from those you know? How do your own beliefs, practices, norms and experiences inform how you understand others’ How do we apply these lenses in our work as global health actors?

Much of our work in public and global health involves encouraging individuals and populations to adopt healthy behaviors. That sometimes means suggesting that people adapt or stop previous behaviors for new behaviors.

But, before we can discuss behavior change in ways that are respectful, informed and inviting it is essential that we understand why people do what they do within the context of their own culture. We also need to reflect on our own identities which shape our beliefs and assumptions related to health and health care seeking — and also our perceptions of others’ beliefs and assumptions which may influence our thoughts on others’ behaviors and beliefs which are different from our own.

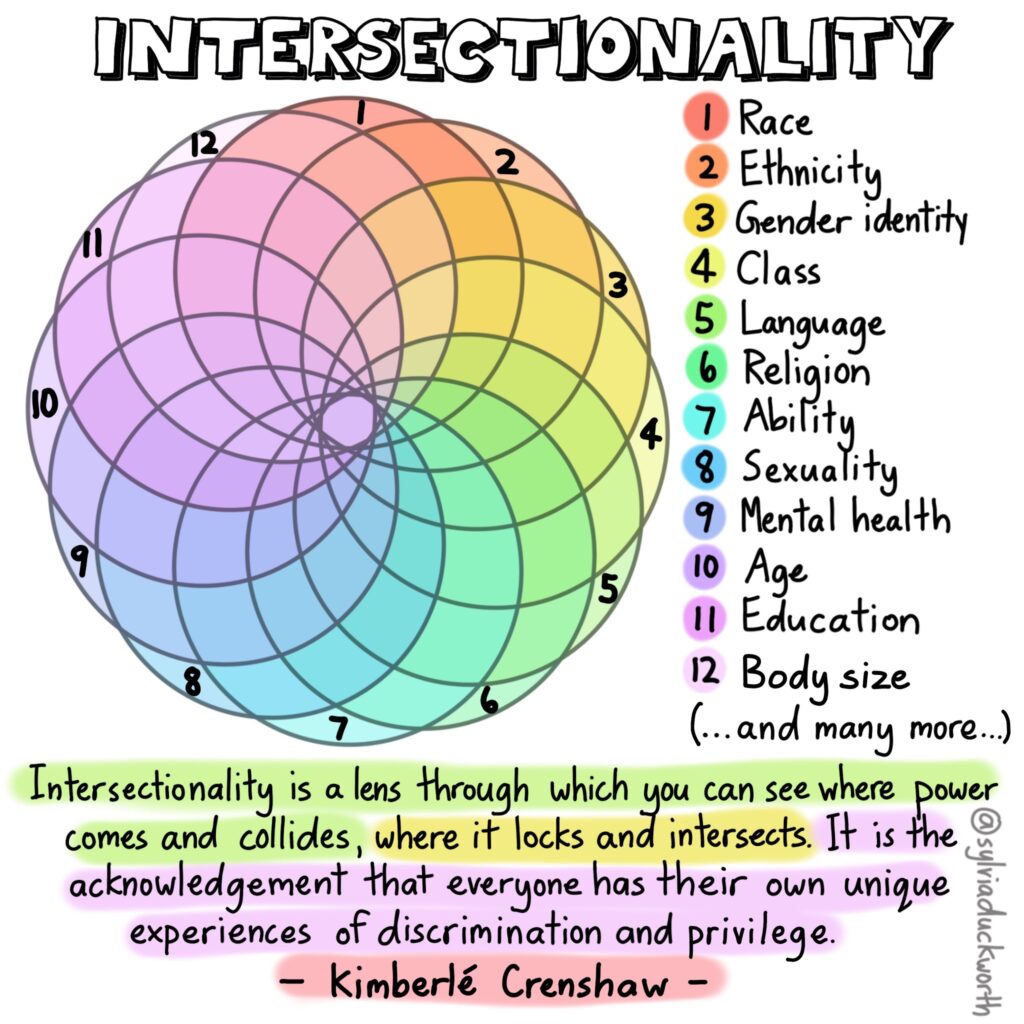

Each of us occupies a unique positionality which is formed at the intersection of our many identities, relative positions of power and privilege and life experiences.

When you think of your identity, what comes to mind?

Is our identity defined by one thing? Or, like the concept of culture, are we defined by a variety of factors? Our identity — or identities — are multifaceted, a combination of who we as well as the life experiences we have had. Our identities shape the ways in which we perceive, understand, judge and value the world around us — and any ‘new’ worlds we encounter.

Look at the graphic below — where do the pieces of your identity intersect to form the ‘lens’ through which you perceive, understand, judge and engage with the world?

- Gender

- Age

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Class

- Nationality

- Ability

- Language

- Sexuality

- Mental health

- Education

- Body size

- …and many more.

As you think about your positionality, or where you are ‘located’ on the graphic below, also reflect on where and how your identity might offer you privilege and create power dynamics in certain spaces.

Intersectionality was coined by the civil rights activist Kimberlé Crenshaw in response to feminist movements of the 20th century to explain how forms of oppression experienced by Black women were distinct from those experienced by white women, or even Black men.

Crenshaw posited that Black women faced unique forms of discrimination because of the intersection of their gender and racial identities and not as a result of being either Black or female alone.

Today, the term intersectionality continues to be important in helping us understand why a person may experience the world differently than others who share similar identities to them, but have a social advantage in one of them. Intersectionality recognizes that social identities such as “women” and “Black” do not exist independently and often converge to construct unique frameworks of oppression that must be first acknowledged in order to create more inclusive dialogue and solutions.

SOURCE: University of Michigan Center for Social Solutions. (2021). Intersectionality, Positionality and Privilege. University of Michigan. https://lsa.umich.edu/social-solutions/news-events/news/insights-and-solutions/infographics/intersectionality–positionality–and-privelege.html

Positionality refers to how differences in social position and power shape identities and access in society…

Misawa (2010, p. 26) emphasizes the fluid and relational qualities of social identity formation while also noting that “all parts of our identities are shaped by socially constructed positions and memberships to which we belong” and are “embedded in our society as a system…In acknowledging positionality, we also acknowledge intersecting social locations and complex power dynamics.”

SOURCE: University of British Columbia. (n.d.) Positionality & Intersectionality. https://indigenousinitiatives.ctlt.ubc.ca/classroom-climate/positionality-and-intersectionality/ Accessed May 19 2021.

How do you think understanding and reflecting on our positionality — or the intersection of our identities and life experiences — is relevant to ethical global health work?

For example, in Public and Global Health research, researchers often need to consider their privilege when conducting their work. Do power imbalances exist between researchers and the participants in their research? How might this affect research participants’ willingness to be open and honest with researchers?

You can also think back to the film Stop Filming Us. Compare the positionality of, for example, the European film maker with the Congolese film makers. Or the positionalities of the Congolese photographer and the refugee communities she photographed? What were the different intersections of identities — and therefore different positionalities — of each of those individuals? How did that affect their ability and power to ‘tell the story’ of Congo?

In the fields of Public and Global Health, understanding our own positionality includes reflecting on why we perceive certain practices or beliefs as ‘different’, ‘right’, ‘wrong’ or ‘strange’? It also involves seeing practices and beliefs from the perspective and positionality of the person who engages in those practices and finds them ‘normal.’ Recognizing, addressing and breaking down these positions of power and power dynamics are all part of our work to decolonize Public and Global Health and ensure our work moves us closer to health equity and justice.

Ethnocentrism and cultural relativism are two perspectives which may help us in processing and understanding of our own positionality, especially as it relates to Public and Global health.

Cultural relativism is the idea that because cultures are unique, they can be evaluated only according to their own standards and values.

(Haviland, 1990)

There are two different categories of cultural relativism.

Absolute cultural relativism considers everything that happens within a culture must and should not be questioned by outsiders.

Critical cultural relativism creates questions about cultural practices in terms of who is accepting them and why. Critical cultural relativism also recognizes power relationships.

(https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Cultural_Anthropology/Introduction, n.d.)

Ethnocentrism is a viewpoint in which which people studying cultures often viewed them from the point of view of their own culture and will judge what they saw to be lacking.

(Skolnik, 2021:168)

Note that a key aspect of ethnocentrism is engaging in value judgments of one culture over another. From an ethnocentric perspective, the culture or practices you perceive as ‘normal’ (because they are what you know best) are considered ‘correct.’ Any other cultural belief or practice that does not line up with your norm will be judged for how it is different in comparison.

How might each of these two perspectives play out in public and global health practice? What might the practical implications be on health outcomes if one perspective informs policy formation over another?

To think these questions through with a practical example, consider the case study below on placenta burial and the reflection questions that follow the case study.

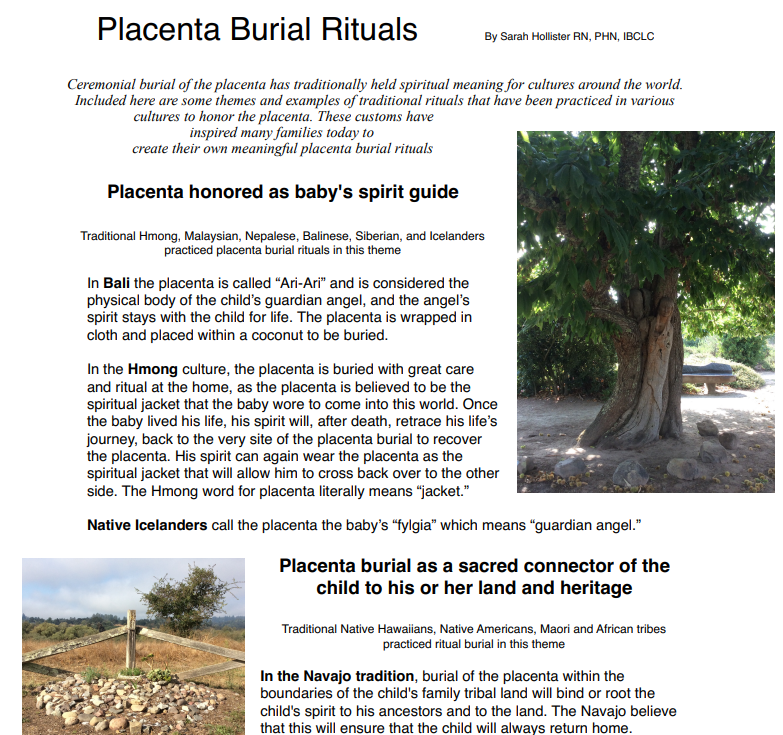

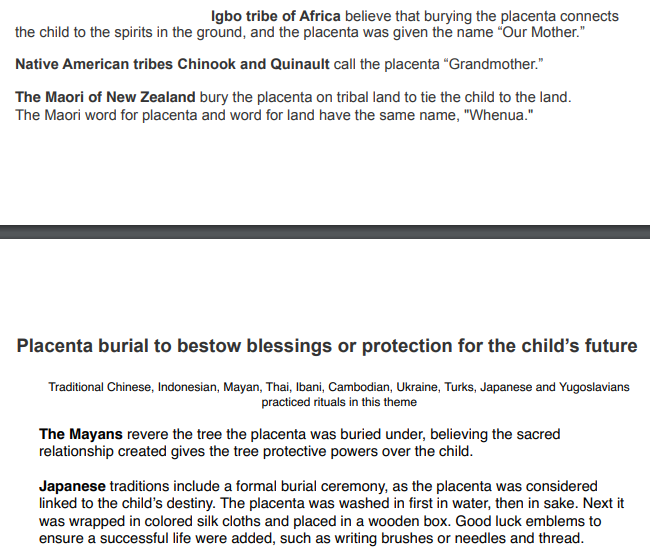

CASE STUDY: Placenta Burial

Understanding the practical implications of ethnocentrism and cultural relativism in health and health care.

Read a short case study on placenta burial rituals from around the world below.

Source: Hollister, S. (n.d.) https://placentarisks.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Placenta-burial-rituals-from-around-the-world-handout.pdf

Now that you have read about some traditions around placenta burial, imagine you are a health care provider in a place like the United States. For most of the American population placenta burial is not a deep-seeded cultural tradition.

What if you are confronted with a patient from one of the cultural backgrounds described in the case study above?

Is placenta burial wrong if it is not a practice recognized by western biomedicine practiced in the United States?

Do individuals giving birth have the right to dispose of their placenta as they choose?

How do you think an individual might be affected if their health care provider states that placenta burial is not important, not medically proven to have benefits or not possible? Do you think the individual seeking medical care will be more or less trusting of that provider? Will the individual feel safe as a patient? What if individuals avoid health care because they do not feel their important cultural practices are recognized, valued and respected?

As the case study demonstrates, the ability to see outside of one’s own perspective is an important skill with practical implications for public and global health actors.

Cultural humility is this process of self-reflection and recognition that our perception of what is ‘normal’, ‘acceptable’ or ‘right’ is just one way of engaging in the world.

Cultural humility is defined as a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his own beliefs and cultural identities.

Sufrin, 2019

Engaging in the process of cultural humility is the ethical responsibility of medical providers as well as Public and Global Health actors.

What is Cultural Diversity?

UNESCO (2001) described cultural diversity as a source of exchange, innovation and creativity, embodied in the uniqueness and plurality of the identities of the groups and societies making up humankind. Cultural diversity, according to UNESCO, isas necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature (2001).

Cultural diversity widens the range of options open to everyone; it is one of the roots of development, understood not simply in terms of economic growth, but also as a means to achieve a more satisfactory intellectual, emotional, moral and spiritual existence.

(UNESCO, 2001)

What is Diversity in healthcare?

Diversity in any workplace means having a workforce comprised of different identities, experiences and perspectives. Healthcare diversity can refer to a number of qualities, including but not limited to the following characteristics: race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, religion, political beliefs, education, physical abilities and disabilities, socioeconomic background, language, culture. Even military service is considered a unique background and experience that should be included in diversity.In other words, it refers to when the medical and administrative staff of a healthcare facility represents a wide range of experiences and background.

The following video discusses cultural diversity in healthcare, specifically in clinical medicine and patient care.

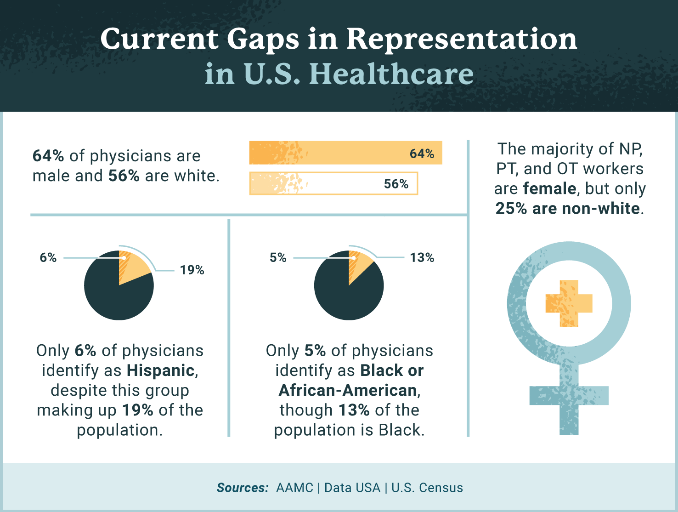

The graphic below demonstrates the current representation gaps in U.S. healthcare staff.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, only about 36% of active physicians are female. Only about 5% of physicians identify as Black or African-American, despite this group making up 13% of the U.S. population, and fewer than 6% of physicians identify as Hispanic, despite Hispanics making up 19% of the U.S. population. However, 28% of physicians and surgeons in the U.S. are immigrants, with doctors from India and China making up the largest groups. This speaks to issues of systemic oppression: people from minority groups that have been [systematically marginalized] for generations in the United States are less represented as physicians than are immigrants of color.

Source: https://www.usa.edu/blog/diversity-in-healthcare/

Why is Healthcare Diversity so important?

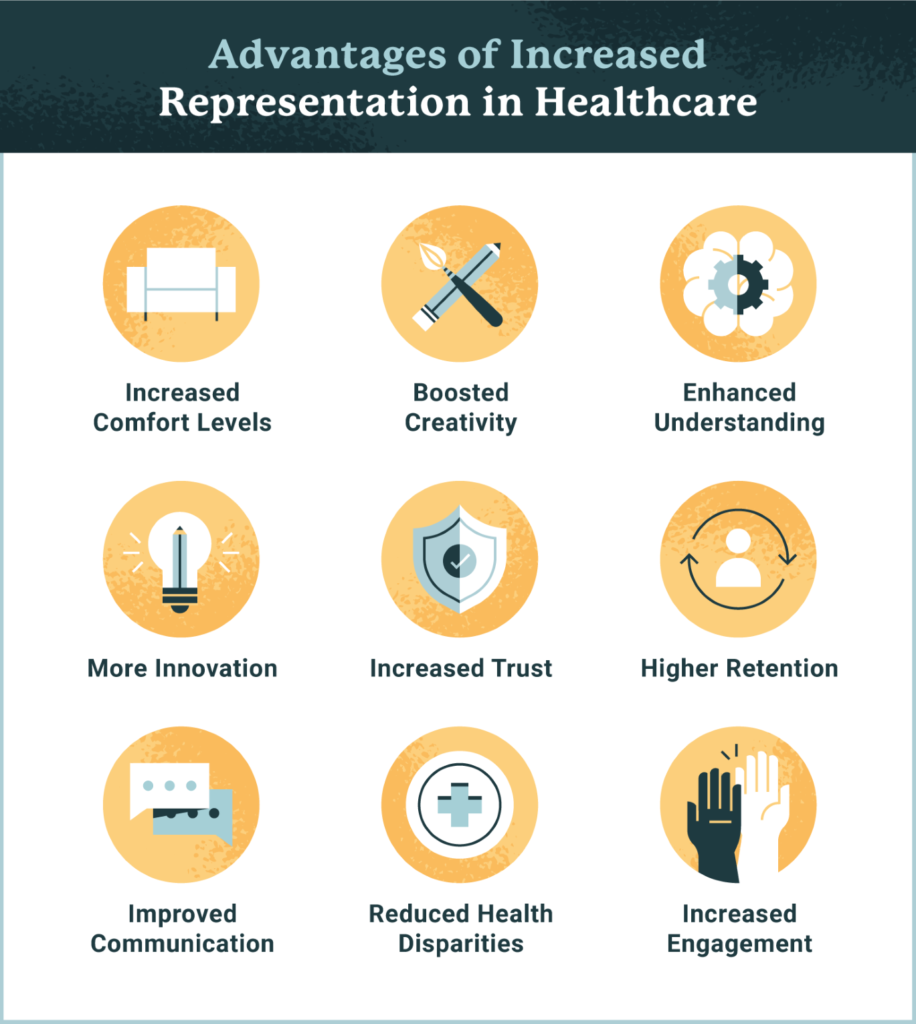

| Benefits of diversity in the healthcare workplace |

| Increased provider comfort levels Studies show that students who have trained at diverse schools are more comfortable treating patients from ethnic backgrounds other than their own. |

| Boosted creativity and innovation A wide range of perspectives can lead to better solutions.11 |

| Enhanced understanding of value sets A more diverse group of healthcare professionals will have a better understanding of colleagues’ and patients’ different belief systems.12 |

| Improved communication Not only may some patients be able to more effectively communicate with providers who speak their language, but they might also receive better care. Patients with limited English proficiency [in English-dominant settings] experience higher rates of medical errors and worse clinical outcomes. |

| Increased patient trust Patients of color may be more likely to seek out care. A Stanford University study found that Black male patients who were treated by Black doctors were more likely to seek preventative services than those who were treated by non-Black doctors. |

| Reduced health disparities Improved cultural competence and ethnic and racial diversity can help to alleviate healthcare disparities and improve healthcare outcomes in diverse patient populations.13 |

| Improved employee engagement and retention People take pride in working for companies that are making a positive impact in society. |

Read the short case study below for an example of the importance and practical applications of integrating cultural diversity into healthcare.

A real-life example: Understanding cultural diversity in healthcare

Pepe Acab, a Filipino patient, was being discharged on Coumadin, a blood thinner, to prevent clotting. Vitamin K reverses the effect of the drug and must be avoided. Normally, Libby, his nurse, would tell such patients to avoid foods like liver, broccoli, brussels sprouts, spinach, Swiss chard, coriander, collards, cabbage, and any green, leafy vegetables. She suddenly realized, however, that there might be other foods he should avoid. She spoke with Mr. Acab and his wife, and got a list of foods he commonly ate. She then did some research and discovered that two foods on the list—soybeans and fish liver oils—are very high in Vitamin K. She was then able to educate him properly on what to avoid.

Source: https://www.ggalanti.org/case-studies-field-reports/

What is Cultural Competency?

Reflecting on our own positionality including our potential biases and positions of privilege, engaging in cultural humility and espousing diversity in healthcare can lead to cultural competency.

Cultural competency in healthcare is the ability of healthcare providers to offer services that meet the unique social, cultural, and linguistic needs of their patients. In short, the better a patient is represented and understood, the better they can be treated.

(Jordan, 2020)

According to Napier et al (2014) “Competence is highly anthropological, embracing culture less as static and stereotypical than as something always in the making. At its best, cultural competence, then, bridges the cultural distance between providers and consumers of health care through an emphasis on physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and emerging skills. Competence is about creation and growth of meaningful relationships.”

In terms of cultural competency in health, “competence is the nurturing of communication between caregivers and patients to remove barriers to care. Therefore, cultural competence can no longer be considered only “a set of skills necessary for physicians to care for immigrants, foreigners, and others from ‘exotic’ cultures”. Moreover, cultural competence should not concern itself exclusively with perceived differences. Culture is less successful when it functions as a medium through which medicine translates clinical realities to uninformed others than when it produces new social circumstances that successfully contextualize clinical knowledge.

Competence should be reconsidered across all cultures and systems of care

Culture is crucial to the sustainability of local healthcare systems, and the strengths and weaknesses of care practices. Competence in health-care delivery can be improved through studying the wellbeing practices of other cultures. Some stable and progressive health systems (eg, New Zealand) have introduced guidelines and stringent cultural competence requirements for health-care professionals. The effects of such guidelines should be studied. The destabilizing consequences of health-care brain drains and worldwide shifts in professional opportunities should also be monitored to establish the effects of health migration on local cultures and their systems and care. Competence awareness, therefore, means not only the introduction of more exploratory thinking into care training to increase awareness of the importance of culture in caring, but also an understanding of how worldwide priorities and health migrations can undermine value-based local caring by eroding fragile resources.

(Napier et al, 2014)

Addressing structural determinants of health: making healthcare Culturally Safe

Structural determinants of health we have discussed — such as colonial legacies of oppression and systemic racism — can cause trauma within communities for generations. This trauma can be intimately tied to past and recent interactions with government systems and agents like the health system and health providers. If individuals do not feel they will receive unbiased, safe care from health providers will they choose to use services at all?

Making health services, research and Public and Global Health work culturally safe is another framework through which health systems, medical and Public and Global Health professionals can work towards justice and equity in health care and health outcomes.

Cultural safety is a focus on improving the delivery of quality healthcare through changes in thinking about power relationships and patients’ rights.

(Papps and Ramsden, 1996)

Why Cultural Safety?

Excerpt from a newsletter of cultural safety trainers in Canada

“Most people are aware of the statistics that indicate significant health and social disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. For example, there are higher suicide rates in the Indigenous population, and Indigenous people tend to have poorer health than other Canadians.1 Indigenous youth don’t graduate from school at the same rate as non-Indigenous youth, and Indigenous children are five times more likely to be in foster care than other children.2

These realities are troubling—as they should be. But what is also important is the context in which these inequities occur, namely, the way social, historical, political and economic factors have shaped and continue to shape Indigenous peoples’ health. This context helps us answer questions such as “Why do Indigenous people have drastically different health and social outcomes?” and “Is there something wrong with the system?” Asking and answering these questions can help to disrupt narratives that blame Indigenous people for the failure to address their own health issues. How we understand these issues, and how we answer these questions, is critical to any action we take.

The concept of cultural safety can be used as a framework for examining and understanding these questions. Originating in New Zealand in the field of nursing education, cultural safety has become an influential perspective in developing better health care for Indigenous people. It differs from concepts such as cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity, cultural competency and cultural humility.

Cultural safety considers the social and historical contexts of health and health care inequities and is not focused on understanding “Indigenous culture.” Many people come to Cultural Safety training program[s] expecting to learn about the formal cultural ceremonies and practices of Indigenous people because they have been led to believe that this is the key to working with people who are culturally different from themselves…Learners are often surprised to learn that a cultural safety approach to providing care is about paying attention to the roots of health and health care inequities, such as colonization.”

(Ward, Branch and Fridkin, 2016)

The following video gives a concise but excellent explanation of cultural safety in healthcare settings.

It is not enough to think about one’s own values, beliefs, and social position within the context of the present moment. In order to practice true cultural humility, a person must also be aware of and sensitive to historic realities like legacies of violence and oppression against certain groups of people. For example, the Public Health Service’s Syphilis Experiment at Tuskegee serves as a tragic reminder of how African Americans have been historically deprived of adequate healthcare and have experienced abuse and disrespect in the name of clinical research.

The history of mistrust between vulnerable populations and public health institutions has led to understandable skepticism about the purpose and outcomes of research. In order to build trust, the historic, systemic reasons for mistrust must be excavated and made visible. These reasons include the history of slavery, racism, segregation, and more recent lived experience of disrespect at the hands of healthcare providers. By recognizing the failures of the past, researchers, clinicians, providers, and advocates can all contribute to building a better future that is founded in practices of cultural humility.

(Sufrin, 2019)

If you did not watch the video below on making health care culturally safe for Aboriginal people during Prelim Engagement, we recommend you watch it now. If you already watched it, you might find it interesting to watch again now that you have read more about culture and health.

As you watch (or re-watch) this clip, keep the concepts of cultural diversity, cultural humility, cultural safety and patterns of resort in mind. Reflect on the tangible actions this health system has taken to combat negative historical and structural determinants of health against Aboriginal people.

Can you think of where they might go even further in tackling negative historical and structural determinants of health?

The bigger picture: Culture, Health and a Culture of Health

In 1988 Masi discussed multiculturalism in healthcare stating that: “Culturally sensitive health care is not a matter of simple formulas or prescriptions that provide a single definitive answer: rather, it requires understanding of the principles on which health care is based and the manner in which culture may influence those principles” and stressed “the importance of understanding community needs, cultures and beliefs; the active interest and participation of the patient in his or her own health care; the importance of a good physician-patient relationship; and the benefit of an open minded approach by physicians and other health-care workers to the delivery of health-care services.” (Masi, 1988).

Later, in 1996, on the occasion of the Year of Culture and Health, Dr. Hiroshi Nakajima, Director General of WHO, and Mr Federico Mayor, Director General of UNESCO, published an editorial stating:

“To reduce sickness and death among mothers and children, to promote family planning, to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, to foster the rational use of health services or the social integration of the disabled, to improve nutrition or to control violence, we must be able to influence behaviours, cultural attitudes and lifestyles. From that point of view, WHO’s community and family health approaches are particularly important for achieving social and cultural relevance in health work. UNESCO also has a major role to play in devising appropriate means of communicating about health so that each community can develop healthy lifestyles that are in harmony with its social, cultural and economic environment.

As health workers and educators we have a twofold responsibility: firstly, to provide equitable access to safe and effective health care and services; and secondly, to provide the necessary knowledge, information and infrastructure that will enable people to take care of themselves and promote their own health and that of their families. To be effective and sustainable, our health policies and interventions, including our education programmes, must be based not only on hard scientific and epidemiological evidence but also on people’s personal experience of life and health and their own priorities and constraints.

To ensure community participation, we must build health development on what people know and what they want and are therefore prepared to support in the long run. We must also be able to rally the cooperation of respected community members such as traditional healers and birth attendants. While maintaining our concern to make safe and effective care of good quality available to all, we must show our willingness both to learn from others and to share our knowledge and experience with them. Much empirical knowledge, for example on medicinal plants, has been accumulated by various cultures and traditions which we must recognize and preserve as part of the common cultural and scientific heritage of mankind” (WHO, 1996).

How are the concepts of Culture and Health framed within policy and practice?

Napier et al (2017) stated that a culturally grounded approach is required to enrich health policies with special attention to be paid to incorporating cultural awareness into policy-making. The aim is to develop “adaptive, equitable and sustainable healthcare systems, and to making general improvements in many areas of population health and well-being”(Napier et al, 2017:vi).

The authors detailed the following reasons for understanding the importance of understanding and integrating cultural contexts to health and well-being policy development. Reflect on how Napier and colleagues’ argument for the integration of culture into healthcare and Public and Global Health contexts references a number of concepts we have discussed in this section so far.

“First, an awareness of cultural contexts shows people the relative nature of values we often assume to be universal. In examining them we challenge ourselves to assess what we take for granted, and to rethink our inductive assumptions about what will make us all healthier.

Second, an awareness of cultural contexts allows us to better understand the compounding influences of diverse but interrelated determinants, such as socioeconomic status, environmental conditions, age, gender, religion, sexual orientation and level of education (6). While alienation and marginalization are key upstream determinants for any number of illnesses and vulnerabilities, cultural understanding can be a source of health resilience in a rapidly changing world.

Third, because pathways of care are built upon a foundation of shared values, an awareness of cultural contexts offers new models of care that take into account more than just biology and medicine.

Fourth, because diverging value systems, health beliefs and views about sharing can either promote or limit the equal distribution of health resources, an awareness of cultural contexts is critical to health equity.

Our experiences of health and well-being are fundamentally influenced by the cultural contexts from which we make meaning. These frameworks inform the beliefs and actions of policy-makers and health care practitioners as much as the people they serve. For this reason, policy-makers must seek not only to understand the values they attribute to others, but also to critically examine their own cultures– their perceptions, daily practices and processes of decision-making – and their effects on people who may or may not share the same values and priorities.”

(Napier et al 2017:xi)

The PEN-3 cultural model

Over the past decade, available evidence focusing on the impact of culture on health has increased dramatically (Airhihenbuwa 2007a; Dutta 2007; Airhihenbuwa and Liburd 2006; Shaw et al. 2009). This indicates not only a widespread and growing interest in the influence of culture but also the realization of its importance in eliminating health disparities, addressing health literacy, and designing and implementing effective public health interventions (Airhihenbuwa and Liburd 2006; Shaw et al. 2009; Airhihenbuwa and Webster 2004). This increasing focus, however, requires a clear understanding of the impact of culture on health.

Culture in this context refers to shared values, norms, and codes that collectively shape a group’s beliefs, attitudes, and behavior through their interaction in and with their environments (Airhihenbuwa 1999). To explore the influence of culture on individual health is ‘to recognize that the forest is more important than the individual tree’ (Airhihenbuwa 1999). Also, exploring the cultural context of the forest allows one to understand and appreciate the ways in which the individual trees are shaped as well as explore the roles, connections, and relationships (whether positive or negative) that exist between the trees (Singhal 2003). These cultural dynamics are essential for public health interventions to be effective and sustainable. Iwelunmor et al (2014) worked on framing the impact of culture on health and, to that end, they developed a cultural model (PEN-3) and applied in public health research and interventions.

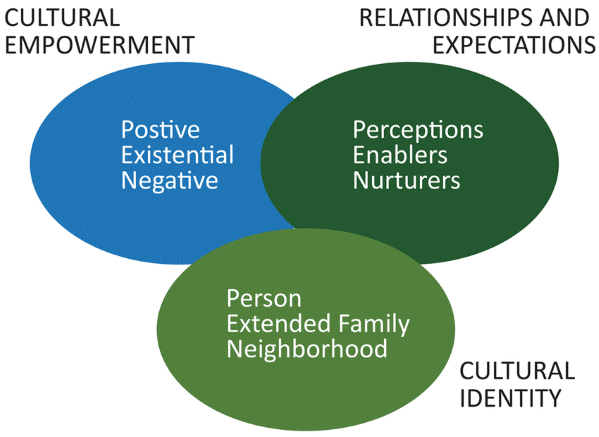

“One model that has been at the forefront of understanding the influence of culture on health is the PEN-3 cultural model (See figure below. Developed by Airhihenbuwa (1989) in response to the apparent omission of culture in explaining health outcomes in existing health behavior theories and models (Airhihenbuwa 1990), the PEN-3 cultural model centralizes culture in the study of health beliefs, behaviors, and health outcomes (Airhihenbuwa 1995). The model also places culture at the core of the development, implementation, and evaluation of successful public health interventions (Airhihenbuwa and Webster 2004; Airhihenbuwa 1995, 2007a). It focuses on the role of culture as a connecting web by which individual perceptions and actions regarding health are shaped and defined (Airhihenbuwa 1995, 2007a, 2007b), while acknowledging that these perceptions and actions are building blocks in constructing health beliefs that are reproduced to express their cultural beliefs (Airhihenbuwa 2007a). Also, the PEN-3 cultural model offers an organizing frame to centralize culture when defining health problems and framing their solutions (Airhihenbuwa 1995, 2007a, 2007b). Moreover, these solutions are framed to encourage and reward positive values, which are better sustained, rather than focusing only on negative values.

The PEN-3 cultural model consists of three primary domains:

(1) Cultural Identity

(2) Relationships and Expectations, and

(3) Cultural Empowerment.

Each domain includes three factors that form the acronym PEN:

Person, Extended Family, Neighborhood (Cultural Identity domain);

Perceptions, Enablers, and Nurturers (relationship and expectation domain);

Positive, Existential and Negative (Cultural Empowerment domain).

The Cultural Identity domain highlights the intervention points of entry. These may occur at the level of persons (e.g., mothers or health care workers), extended family members (grandmothers), or neighborhoods (communities or villages). With the Relationships and Expectations domain, perceptions or attitudes about the health problems, the societal or structural resources such as health care services that promote or discourage effective health-seeking practices, as well as the influence of family and kin in nurturing decisions surrounding effective management of health problems are examined. With the Cultural Empowerment domain, health problems are explored first by identifying beliefs and practices that are positive, exploring and highlighting values and beliefs that are existential and have no harmful health consequences, before identifying negative health practices that serve as barriers.

In this way, cultural beliefs and practices that influence health are examined whereby solutions to health problems that are beneficial are encouraged, those that are harmless are acknowledged, before finally tackling practices that are harmful and have negative health consequences.”

Excerpt from Iwelunmor, J., Newsome, V., & Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2014). Framing the impact of culture on health: a systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethnicity & health, 19(1), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2013.857768

Source: Airhihenbuwa et al 2020

What is a Culture of Health?

A culture of health is broadly defined as one in which good health and well-being flourish across geographic, demographic, and social sectors; fostering healthy equitable communities guides public and private decision making; and everyone has the opportunity to make choices that lead to healthy lifestyles

(Evidence for Action, n.d.)

A culture of health requires respecting the many cultural traditions … and a discourse that honors our differences as it advances our common interests.

Plough, 2020

About a culture of health

“A culture of health means placing well-being at the center of every aspect of our lives. In a Culture of Health, [we] understand that we’re all in this together—no one is excluded. Everyone has access to the care they need and a fair and just opportunity to make healthier choices. In a Culture of Health, communities flourish and individuals thrive.

A Culture of Health is broadly defined as one in which good health and well-being flourish across geographic, demographic, and social sectors; fostering healthy equitable communities guides public and private decision making; and everyone has the opportunity to make choices that lead to healthy lifestyles. This requires that society be free of systems and structures that perpetuate racial inequities.

The exact definition of a Culture of Health can look very different to different people. A national Culture of Health must embrace a wide variety of beliefs, customs, and values. Ultimately, it will be as diverse and multifaceted as the population it serves.

– Robert Wood Foundation

(https://www.rwjf.org/en/cultureofhealth/about.html)

How can we build a Culture of Health?

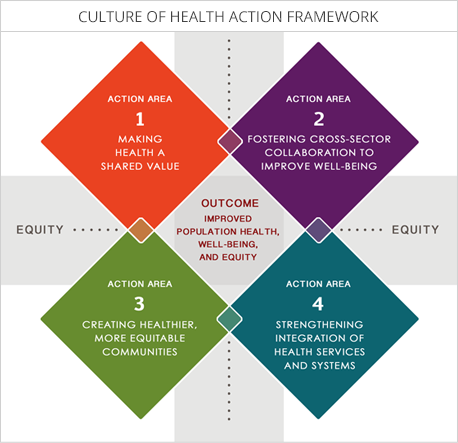

Chandra et al (2017) provided the background on the development of an action framework placing “well-being at the center of every aspect of life, with the goal of enabling everyone in our diverse society to lead healthier lives, now and for generations to come” (p.1). Considering that “health is a function of more than medical care, the authors argue that solutions to U.S. [and other countries’] health problems must encompass more than reforms to health care systems. …. The Culture of Health action framework is designed around four action areas and one outcome area. Action areas are the core areas in which investment and activity are needed:

(1) making health a shared value;

(2) fostering cross-sector collaboration to improve well-being;

(3) creating healthier, more equitable communities; and

(4) strengthening integration of health services and systems.

Source: https://www.policiesforaction.org/what-culture-health

Summary

We know there was a lot of information to absorb in this section of reading. The main ideas to take away are that culture and health are inherently interconnected for each of us. Cultural beliefs, practices and norms influence not only health behaviors and health care seeking, but also the perspectives and work of health providers and Public and Global Health actors. Considering the influences of our culture and positionality, as well as the cultures and positionalities of individuals and populations we work closely with as Public and Global Health actors, are essential, ethical reflections necessary to move us closer to health equity and justice around the world.

Supplementary Resources

Building a Culture of Health: What Does it Take? https://youtu.be/__lq-znG–w

Chandra, A., Acosta, J., Carman, K. G., Dubowitz, T., Leviton, L., Martin, L. T., Miller, C., Nelson, C., Orleans, T., Tait, M., Trujillo, M., Towe, V., Yeung, D., & Plough, A. L. (2017). Building a National Culture of Health: Background, Action Framework, Measures, and Next Steps. Rand health quarterly, 6(2), pp 1-11.

Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, Calabrese J, Chater A, Chatterjee H et al. Culture and health. Lancet. 2014; 384: pp 1612-1617.

Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, Calabrese J, Chater A, Chatterjee H et al. Culture and health. Lancet. 2014; 384: pp 1618-1629.

Hofstede’s 6-D Model of National Cutlure: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=TF47NnxACdg&feature=youtu.be

Iwelunmor, J., Newsome, V., & Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2014). Framing the impact of culture on health: a systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethnicity & health, 19(1), 20-46, pp 1-2 & 11.

Reimagined in America Webinar: Taking a well-being approach: https://youtu.be/IufDVQqGBZE

Reimagined in America Webinar: Building Inclusive Healthy Places: https://youtu.be/W9Dlde_19EU

References

References Section 3.11 Understanding the role of Culture in Health?

- American Association of Diabetes Educators. (2015). Cultural considerations in diabetes education. AADE Practice Synopsis. Chicago, IL: American Association of Diabetes Educators. Available at: https://www.diabeteseducator.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/cultural-considerations-in-diabetes-management.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- Airhihenbuwa, Collins & Iwelunmor, Juliet & Munodawafa, Davison & Ford, C.L. & Oni, T. & Charles, Agyemang & Mota, C. & Ikuomola, O.B. & Simbayi, Leickness & Fallah, M.P. & Qian, Z. & Makinwa, B. & Niang, Cheikh & Okosun, Ike. (2020). Culture Matters in Communicating the Global Response to COVID-19. Preventing Chronic Disease. 17. 10.5888/pcd17.200245.

- Barnard Health Care. (2020). Health Seeking and Patterns of Resort. https://www.barnardhealth.us/medical-anthropology/healthseeking-and-patterns-of-resort.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, June 9). Social determinants of health, health equity, and vision loss. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/determinants/index.html

- Chandra, A., Acosta, J., Carman, K. G., Dubowitz, T., Leviton, L., Martin, L. T., Miller, C., Nelson, C., Orleans, T., Tait, M., Trujillo, M., Towe, V., Yeung, D., & Plough, A. L. (2017). Building a National Culture of Health: Background, Action Framework, Measures, and Next Steps. Rand health quarterly, 6(2), 3.

- Cultural Anthropology. (N.d.) https://courses.lumenlearning.com/culturalanthropology/

- Evidence for Action. (n.d.) What is a Culture of health? https://www.evidenceforaction.org/about-us/what-culture-health).

- Haviland, W.A. (1990). The nature of culture. In Cultural Anthropology (6th ed). Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc.

- Hiratsuka, V. Y., Trinidad, S. B., Avey, J. P., & Robinson, R. F. (2016). Application of the PEN-3 model to tobacco initiation, use, and cessation among American Indian and Alaska Native adults. Health promotion practice, 17(4), 471-481.

- Iwelunmor, J., Newsome, V., & Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2014). Framing the impact of culture on health: a systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethnicity & health, 19(1), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2013.857768

- Jordan, A. (2020). The Importance of Divesrity in Healthcare & How to Promote it. Provo College. https://www.provocollege.edu/blog/the-importance-of-diversity-in-healthcare-how-to-promote-it/

- Masi, R. (1988). Multiculturalism, medicine and health Part I: Multicultural health care. Canadian Family Physician, 34, 2173.

- Matsuura, K. (2005). Appendix I UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Diogenes, 52(1), 141-145.

- Napier, A. (2014). David et al. “Culture and health”. The Lancet, 384(9954), p1607-1639. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/neglect-of-culture-in-health

- Napier A. D., Ancarno, C., Butler, B., Calabrese, J., Chater, A., Chatterjee, H., … & Woolf, K. (2014). Culture and health. The Lancet, 384(9954), 1607-1639. pp 1632)

- Napier, D., Depledge, M. H., Knipper, M., Lovell, R., Ponarin, E., Sanabria, E., & Thomas, F. (2017). Culture matters: using a cultural contexts of health approach to enhance policy-making. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

- Plough, A. L. (2020). Culture of Health in Practice: Innovations in Research, Community Engagement, and Action. Oxford University Press.

- Skolnik, R. (2021). Global Health 101 (4th ed). Burlington, MA. Jones and Bartlett Learning.

- Sufrin, J. (2019). Three things to know: Cultural Humility. Hogg Foundation for Mental Health. https://hogg.utexas.edu/3-things-to-know-cultural-humility

- University of British Columbia. (n.d.) Positionality & Intersectionality. https://indigenousinitiatives.ctlt.ubc.ca/classroom-climate/positionality-and-intersectionality/ Accessed May 19 2021.

- UNESCO. (2010). 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics. Institute for Statistics of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/doc10/BG-FCS-E.pdf

- UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. (2001). Available at: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13179&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- Ward, Branch and Fridkin. (2016). What is Indigenous Cultural Safety – and why should I care about it? Here to Help. https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/visions/indigenous-people-vol11/what-indigenous-cultural-safety-and-why-should-i-care-about-it

- WHO (1996). Culture and health. 49(2) : 3-31. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/50204

- WHO. (2019). WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312342/9789241515436-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y