2. Key Concepts

- Representation

3. Prelim Engagement

- Watch the film’s trailer:

- Read this interview with the filmmaker: Stop Filming Us: Interrogating and Inverting the Western Gaze

- Read this film review: Stop Filming Us’ Review: Wary of Their Close-Up

The reading content for this section is minimal as the main Learning Activity for this section is to watch a full-length documentary film, Stop Filming Us.

While watching the documentary, we suggest you reflect on all of the concepts, themes and discussions we have engaged in so far in this course. Most of this film does not directly address Global Health. However, we are asking you to think critically — and make those connections, relationships and links between the conversations and perspectives that emerge from the film and conversations we are having specifically about the field of Global Health.

For example, how are histories of colonialism and neocolonialism discussed in the film Stp Filming Us — and how are these histories determinants of health in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo?

How do the ‘Western Gaze’, representation and white saviorism shape the field of Global Health? What do these dynamics mean in reality? How do they have an impact on Global Health outcomes from individuals and populations in low- and middle-income countries?

One specific concept you should take away from this section and which will emerge in the film Stop Filming Us is representation.

The concept of representation is used in many different ways and can refer to different populations and relationships, depending on academic or professional field and context. As you watch the film, reflect on how representation is relevant to the specific narrative of the film but also the fields of Global Health, international development and humanitarianism. Work where ‘outsiders’ come ‘in’ — and have a particular story to tell about people, places and time.

Representation is defined as the action of speaking or acting on behalf of someone; the description or portrayal of someone or something in a particular way or as being of a certain nature.

(OER, 2021)

To make the concept of representation ‘real’ — try a quick internet search for images of ‘news Democratic Republic of Congo.’ What are the first images that you see?

Source: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/12/15/more-than-dozen-killed-in-eastern-dr-congo-rebel-attack

Now do the same thing for a high income country — like the United States. What are the first images you see if you search ‘news United States’?

What strikes you about the differences between the groups of images that come up for each search?

This is representation, in one of the many ways it relates to Global Health. Keep the results of this exercise in mind as you screen the film Stop Filming Us.

Stop Filming Us

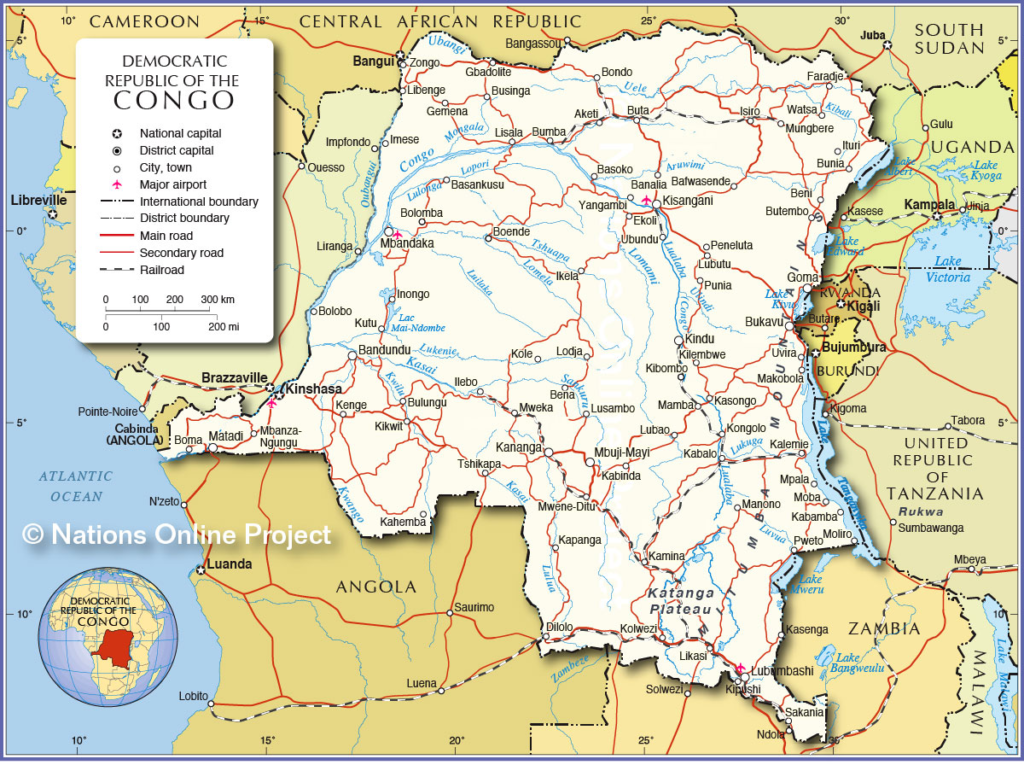

The film Stop Filming Us was filmed in the city of Goma in the province of North Kivu, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

The DRC is in central Africa. It is also referred to as the RDC (French abbreviation), RD-Congo, DR-Congo or Congo-Kinshasa. The capital, Kinshasa, is located in the far west of the country.

The DRC should not be confused with the Republic of Congo (capital Brazzaville) which shares the western border with DRC but is much smaller in area and population.

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Democratic_Republic_of_the_Congo_in_Africa.svg

SOURCE: https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/dr_congo_map2.htm

Parts of the film reference and discuss histories and contemporary realities of the ‘Kivu Region.’. The Kivus — North Kivu and South Kivu — are provinces in eastern DRC that border the countries of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. Goma, where the film is based, is a major city in North Kivu province on the border of Rwanda. Goma sits on the northern shores of Lake Kivu, a massive freshwater lake that separates DRC from Rwanda.

We will not go into detailed histories of the country or region here, but suggested Supplementary Readings can be found below. The DRC’s colonial and post-colonial histories illustrate many of the dynamics we discussed in Section 1.5 on Colonial and Neocolonial histories and their intersections with Global Health. The DRC, the eastern region in particular, became deeply entangled in the aftermath of the Rwandan Genocide (1994). The spillover of the Genocide led to a regional conflict over the next decades, referred to as the African Great War (Merchant, 2020). Millions of lives have been lost in the region to direct violence but also to disease and famine (Merchant, 2020). Have you ever heard of the African Great War? If you answered ‘no’ — this is also a question of representation. Why have many — or most of us — never heard of this huge regional conflict that spanned decades and claimed an estimated millions of lives?

What is very important to remember, however, is that while these horrific histories are true — they are only one aspect of the DRC story. We hope, above all, the film Stop Filming Us communicates this to readers — that representation matters and that certain places are only ever represented in one way, depending on who is telling the story.

American author Jason Stearns, as an outside westerner, captured his perspective on this diverse and dynamic country:

The Congo (DRC) is not just blood and gore. It also has an incandescent, raw energy to it, a dogged hustle that can be seen in street-side hawkers and besuited minister alike…This is the paradox of the Congo: Despite its tragic past, and probably in part due to the self-reliance and ingenuity resulting from state decay, it is one of the most alive places I know.

Stearns, 2011:xix

Source: www. berejst.dk/389/Goma.htm in McKnight (2014).

Students will find it very helpful to understand more of the past and recent history of the DRC before watching the film to give context to a number of scenes and conversations that take place.

As you review these timelines, think back to the histories of colonialism and neocolonialism we discussed in Section 1.5 — do you see any of these narratives in the history of the DRC? Colonialism? Congolese independence? Neocolonialism, such as Structural Adjustment Programs? Some condensed historic timelines can be located via the links below.

→ Students may also want to reflect on how these historic timelines, produced by western-based organizations, represent the country’s history.

| Brief histories of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Democratic Republic of Congo profile – Timeline (BBC) DR Congo: Chronology (Human Rights Watch) Not freely available but a DRC history written by a Congolese intellectual and historian: The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History by Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja |

After completing the short pre-readings and engagement above, we ask that students screen the documentary film Stop Filming Us available via The Video Project.

| University of Illinois-Chicago students: Students enrolled in an in-person class — We will screen the first half of the film in class, then you will be required to view the rest of the film as homework. You will find a link on our course Blackboard site. Students enrolled in an online, asynchronous course — You will find a link to the film on our course Blackboard site. |

As you watch this film, reflect on how the themes, conflicts, histories and power dynamics explored:

- Stem from histories of colonialism and historical and contemporary racism aimed at marginalizing Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) and other groups?

- Affect the prioritization and formation of Global Health and humanitarian policies and actions?

- Benefit certain populations (white, western, high-income professionals and governments)?

How is eastern DRC represented?

Can representation be a determinant of health? For whom? And how?

Finally, is this film a good medium through which to start and have these conversations?

Or, does this film — directed by a white, western man — only reiterate and reify existing, problematic power dynamics?

UIC STUDENTS please proceed to our course Blackboard site, Learning Content Section 1.6: Stop Filming Us for a link to the film.

You will need to sign in with your UIC NetID and Password.

Reminder: enable the ‘Closed Captions’ (CC) on for translated subtitles

References

OED (2021). Via Google Search. https://www.google.com/search?q=representation&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS800US800&oq=representation&aqs=chrome.0.69i59l3j0i131i433i512l2j69i61j69i60l2.5412j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

McKnight, Janet. (2014). Surrendering to the Big Picture: Historical and Legal Perspectives on Accountability in the Democratic Republic of Congo Following the Defeat of the March 23 Movement. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development. 3. 10.5334/sta.de.

Merchant, Zofsha. (2020). Democratic Republic of the Congo. World Without Genocide. http://worldwithoutgenocide.org/genocides-and-conflicts/congo

Stearns, Jason. (2011). Dancing in the Glory of Monsters. Public Affairs. New York.

Supplementary Resources

Histories of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Stearns, Jason. (2011). Dancing in the Glory of Monsters. Public Affairs. New York.

Representation & The Western (or foreign) Gaze