2. Key Concepts

- Historical determinants of Health

- Colonialism

- Neocolonialism

- Colonial Medicine

- Tropical medicine

- International Health

- Alma Ata Declaration

- The Washington Consensus

- Structural Adjustment Programs

- User fees

- White savior complex

- Decolonization

- Indigenization

3. Prelim Engagement

- Read this article: The Legacy of Colonial Medicine in Central Africa

- Watch this video clip:

- Watch this video clip:

Why history?

Wait, what? A history lesson? I thought this was a course on Global Health. Doesn’t Global Health deal with the present? Contemporary health challenges that transcend national boundaries? Why are we talking about history?

These are all excellent questions. In fact, many Global Health courses and textbooks do not touch on history at all. To be fair, there is a lot of information and a number of current Global Health crises to discuss without having to go back in time a couple centuries. Especially in one semester.

However, if you do not look back, you will not fully understand the present. And, without considering history, Global Health interventions risk failure — or making inequities worse off than they were before.

To explore these ideas further, let’s think back to the previous section when we discussed the social and structural determinants of health. As a reminder:

The structural determinants of health are “the ‘root causes’ of health inequities, because they shape the quality of the Social Determinants of Health experienced by people in their neighborhoods and communities. Structural determinants include the governing process, economic and social policies …The structural determinants affect whether the resources necessary for health are distributed equally in society, or whether they are unjustly distributed according to race, gender, social class, geography, sexual identity, or other socially defined group of people.

(IDPH, n.d.)

One thing we want to explore in this section is how are structural determinants of health, and more specifically Global Health, shaped? How did they come to be? And how and why do they perpetuate such drastic inequities in the distribution of resources necessary for achieving economic development and optimal health?

The answer lies in history.

Just a note that this section focuses on global economic and political histories with a specific focus on the effects of colonialism and neocolonialism on African populations and countries. There are also many words to be written about the effects of colonialism on Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) and other systematically marginalized people around the world, including in the United States. By centering histories of the African continent we are not devaluing other BIPOC histories. We aim to explore those histories in more depth throughout this course.

Poor countries are poor for a reason. In fact, many reasons.

The inequitable distribution of wealth, resources and health did not just happen by chance. It was not always this way. The designations of low-, middle- and high-income countries are by no means ‘natural’ or given.

By the end of this section you will see that historical events, conscious decisions, and, in some cases, unintended consequences of those decisions over the past centuries have all brought us to the Global Health injustices and successes we continue to discuss in this course.

History, therefore, is a determinant of health.

History as a Determinant of Health

Excerpt from a letter from Dr. Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A Knox Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

The social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape the health of populations are not just the products of contemporary circumstance; they are part of an historical continuum. The effect that historical factors like war, economics, intellectual movements, and mass migration can have on the long-term health of populations argues for a consideration of the past itself as a determinant of health…

The arc of history can teach us much, particularly—as it relates to the concerns of public health—by fostering an understanding of how factors that may not seem [relevant] to health at a fixed historical moment are often deeply relevant in the long run.

Consider the rise of US life expectancy during the 20th century. In 1900, life expectancy in this country was about 47 years. It is now about 79 years. What accounts for this shift? To someone with the dramatic technological breakthroughs of the last century fresh in mind as they consider the latter half of that century, the answer would likely seem easy: better drugs and treatments. It is not difficult to see why this opinion might prevail—from vaccines, to surgical procedures, to advances in genomics, the 20th century was undeniably a time of amazing medical progress, and this progress has certainly helped to prolong life. However, a broader look at the history of the period suggests that the fundamental difference was made by steady improvements in living standard…better nutrition, and signal achievements in public health. An historical perspective therefore helps us to recognize what has mattered most over time, and what might matter today, and in the future.

History also sheds light on the roots of present-day health disparities in the US. This is especially true in the case of American slavery, and the legacy of Black marginalization that we continue to live with. The most overt consequence of slavery, our country’s ugly history of racism, has shaped our society in many ways, with direct implications for public health.

Take, as one example, the area of housing policy…Housing, and housing affordability, affect everything from our proximity to residential exposures—shaping early childhood development—to the presence of fire hazards, to income. The burden of poor housing has historically been, and remains, disproportionately borne by Blacks. About 7.5 percent of non-Hispanic blacks live in substandard housing, compared to just 2.8 percent of whites.

This disparity is the result of a mix of government policies and real estate dealings that have created a kind of de-facto segregation in many of our cities. Chicago is a case in point. 500,000 blacks moved to the city between 1916 and 1970 as part of the Great Migration—a period when more than six million blacks moved from the rural South to cities in the North, Midwest, and West to find economic opportunities and escape the restrictions of Jim Crow. During this time, Chicago real estate commissions adopted racially restrictive policies to “contain” the black population in certain parts of the city.

In the 1930s, these practices were bolstered by New Deal-era “redlining” policies, which codified racial prejudice into the insurance and lending policies of the federally-funded Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, laying the groundwork for housing disparities that persist to this day. As we work to mitigate these disparities, an awareness of how they arose helps us to see that fair housing is not just a question of promoting smarter, healthier policies; it is a question of correcting an historical injustice.

(Galea, 2017)

As we move through the rest of this course and begin to explore specific health challenges facing the world today, keep these different determinants of health in mind. When confronted with a Global Health challenge, ask yourself which social, structural and historical determinants may have and may be contributing to that challenge in different ways? And, most importantly, how might understanding those determinants help us formulate solutions to realize greater Global Health equity and justice? As Black American scholar, feminist and activist Dr. Angela Davis said:

…the ultimate significance of knowledge is its capacity to transform our social worlds.

(Davis A, 2018: ix)

As the excerpt above from Dr. Galea on the historical determinants of health suggests, there are so many ways to discuss, explore and understand the historical determinants of health. Each health challenge, policy, success and disparity we examine has a unique history to unearth, understand and consider in our actions and solutions as Global Health actors.

In this section, we are going to take a more macro-view of determinants of health and focus on histories of colonialism and neocolonialism.

→ First, we want to uncover the power dynamics, politics, racism and economics that have led to such drastic economic and health disparities around the world. As mentioned before — poor countries were made poor, and remain poor, for many reasons!

Uncovering the colonial roots of Global Health

Did you know that the field of Global Health can actually trace its roots back to colonialism?

Colonialism is defined as “control by one power over a dependent area or people.” It occurs when one nation subjugates another, conquering its population and exploiting it, often while forcing its own language and cultural values upon its people. By 1914, a large majority of the world’s nations had been colonized by Europeans at some point.

(Blakemore, 2019)

→ We will trace the roots of the field of Global Health and understand how this field came to be, from colonialism beginning in the early 1800s to contemporary global economic policies in existence today. While European colonization was happening around the world, we will draw many of our examples from colonization on the continent of Africa.

→ This kind of historical exploration is also important because of the tangible impacts colonial legacies have on Global Health today. Discrimination, racism, oppression and often brutal violence and death were the tools colonizers used to gain and maintain power in the colonies, and continue to make economic profits off of the people and lands they occupied. These injustices spread into the realm of Public Health (see The Legacy of Colonial Medicine in Central Africa). Therefore, health and non-health related colonial practices and power dynamics, even from centuries ago, continue to have an impact on how populations around the world today perceive and (dis)trust Global Health interventions (Lowes and Montero, 2018).

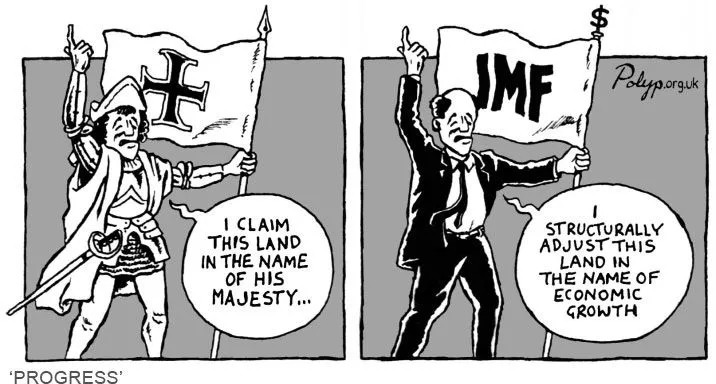

→ The direct colonization of other lands and peoples by European nations ‘officially’ ended around the 1960s with a wave of African independence movements. However, economic and social policies created and enforced by former colonizing nations as well as countries like the United States, Canada and Australia continued well past the 1960s — and still exist today. This kind of economic and political control is known as neocolonialism. Neocolonial policies dictated Global Health policy and planning from the mid-20th century, and continues to do so in the present.

Neocolonialism is the use of economic, political, cultural, or other pressures to control or influence other countries, especially former dependencies.

(OED, 2021)

Neocolonialism is the control of less-developed countries by developed countries through indirect means. The term neocolonialism was first used after World War II to refer to the continuing dependence of former colonies on foreign countries, but its meaning soon broadened to apply, more generally, to places where the power of developed countries was used to produce a colonial-like exploitation—for instance, in Latin America, where direct foreign rule had ended in the early 19th century. The term is now an unambiguously negative one that is widely used to refer to a form of global power in which transnational corporations and global and multilateral institutions combine to perpetuate colonial forms of exploitation of developing countries. Neocolonialism has been broadly understood as a further development of capitalism that enables capitalist powers (both nations and corporations) to dominate subject nations through the operations of international capitalism rather than by means of direct rule.

(Halperin, n.d.)

→ Finally, as one more response to ‘why history?,’ let’s reflect on this quote before we dive any deeper:

Certain nations hold historic responsibility for the current health and economic inequities between countries around the world.

Ask yourself: who benefits by not uncovering or discussing these histories?

Bringing history to the forefront of discussions about reducing Global Health and economic disparities will bring us one step closer to holding countries and institutions responsible for the violence and inequities around the world accountable to their actions. In short, it is easier (and much less expensive) for high-income countries to avoid these discussions and, therefore, their responsibility in creating and perpetuating inequity.

So, let’s begin peeling back the layers of history to uncover the systems feeding our tree. We will start with colonial medicine.

SOURCE: https://www.thepraxisproject.org/social-determinants-of-health

Colonial Medicine lays the foundations

The transatlantic slave trade began as early as the 15th century, led by the Portuguese. Over the next 400 years, an estimated 11 million Africans would be transported across the Atlantic to the Americas and the Caribbean (called the West Indies by Europeans at the time) (Adi, 2012). Over two million Africans died on this horrific journey (BBC, 2021). Nigerian culinary scholar Ozoz Soko fittingly described the transatlantic slave trade as the “greatest brain drain in history” (2021).

The slave trade was abolished in the early 1800s and slavery itself mid-century (Adi, 2012).

The atrocities committed during this period of history are the inarguable roots of contemporary social and health disparities experienced by Black communities around the world. The intergenerational effects of centuries of systemic discrimination and racism against Black communities, beginning with slavery, is perhaps most visible in the United States. We will introduce and discuss the concepts of historical trauma, intergenerational trauma and their tangible effects on health outcomes for particular individuals and populations in a future section of reading.

If you would like to explore racism, intergenerational trauma and effects on health outcomes this [optional] video offers some initial perspectives. We will explore this concept in more depth in later sections.

Intergenerational trauma is ‘pain’ passed down generations, hurting Black people’s health

From the 15th-early 19th centuries, European contact with and colonization of the African continent was mostly contained to coastal areas. Interior exploration of the continent by Europeans was limited, largely because of infectious diseases that were killing white colonists. European mortality rates on the Gold Coast of West Africa (present day Ghana), for example, were shockingly high — estimated at 300-700 deaths per 1,000 population in the first year of settlement (Greene et al, 2013).

European military, exploratory and profit-making campaigns in Africa would never be successful if Europeans were dying at such high rates. Europeans needed to find ways to treat diseases they encountered in tropical climates to which they had no immunity.

At the same time, the very objective of the colonial project was to make money off of colonized lands by forcing local populations to work for little to no compensation. If the colonized populations were also not healthy they could not work as hard, they could not have healthy children and the colony would not be as profitable. The field of colonial medicine, therefore, contributed to early colonial expansion into the African continent by keeping both European colonists and native Africans healthy.

Colonial medicine originated to support the [European] military, before broadening to include European-born administrators and civilians, with services therefore concentrated in important ports and urban centers.

Beyond that, colonial medicine expanded to protect the health of the laboring populations insofar as local labor was required to run the vast plantations and mines that extracted economic resources for colonial interests.

(Greene et al., 2013)

If you watch the animation below, beginning around minute 2:15, you will see that European expansion into the continent of Africa was limited until about the 1880s. This coincides with the expansion and professionalization of colonial medicine as well as greater understanding of how disease is spread. Concepts of disease prevention and the birth of Public Health (think back to Section 1.2 and John Snow’s investigation of cholera in London in 1854) helped move the European colonial project forward.

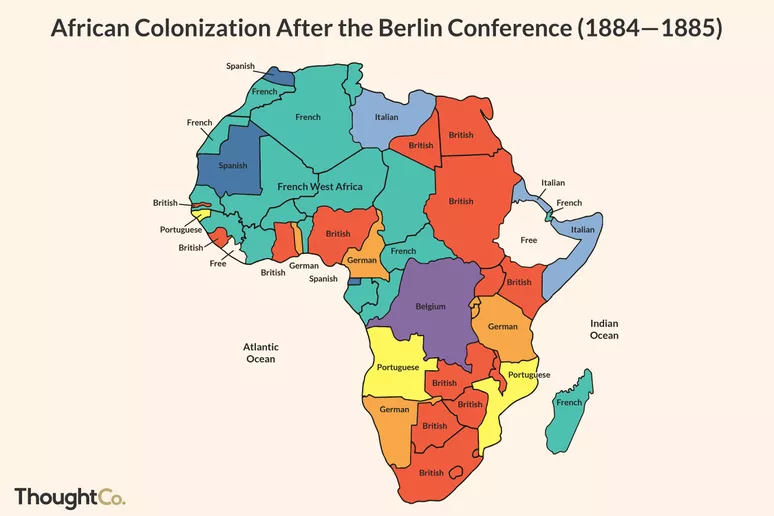

The Berlin Conference, Tropical Medicine & Sowing the Seeds of Medical Distrust

After some decades of gradual expansion into Africa, European powers held a conference to essentially divide the continent of Africa between them as one might cut a pie into slices. At the end of the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, lines were drawn on maps to make colonies and were ‘given’ to different European powers. These lines drawn by white Europeans — with no African leaders in the room — divided already-existing African kingdoms, ethnicities and language groups. The decisions taken at the Berlin Conference made colonies, and what would later become nations, out of groups of populations which often had little to nothing in common.

In 1884, at the request of Portugal, German chancellor Otto von Bismark called together the major western powers of the world to negotiate questions and end confusion over the control of Africa. Bismark appreciated the opportunity to expand Germany’s sphere of influence over Africa and hoped to force Germany’s rivals to struggle with one another for territory.

At the time of the conference, 80 percent of Africa remained under traditional and local control. What ultimately resulted was a hodgepodge of geometric boundaries that divided Africa into 50 irregular countries. This new map of the continent was superimposed over 1,000 indigenous cultures and regions of Africa. The new countries lacked rhyme or reason and divided coherent groups of people and merged together disparate groups who really did not get along…

The Berlin Conference was described by Harm J. de Bli in “Geography: Realms, Regions, and Concepts:”

“The Berlin Conference was Africa’s undoing in more ways than one. The colonial powers superimposed their domains on the African continent. By the time independence returned to Africa in 1950, the realm had acquired a legacy of political fragmentation that could neither be eliminated nor made to operate satisfactorily.”

(Rosenberg, 2019)

SOURCE: ThoughtCo / Adrian Mangel, https://www.thoughtco.com/berlin-conference-1884-1885-divide-africa-1433556

As mentioned, the ultimate aim of colonization was to make money for European colonizing nations. While we are focusing on the African continent in this reading, it is essential to remember that in the United States, Canada and Australia similar systems had been in place since the arrival of white settlers onto those lands. In North America settlers had been arriving since the 1500s and in Australia from the late 1700s (National Geographic, 2021, Muswellbrook Shire Council, 2020). White settlers continued to expand land holdings by stealing land from Indigenous peoples including Native Americans in the United States, First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples in Canada and Aboriginals in Australia.

Colonization, subjugation and profit-making in the colonies was often achieved through brutal tactics of coercion, forced labor and outright slavery. Horrific stories of violence and exploitation committed by colonial agents in the name of ‘civilization’, racist notions of superiority, religion and economic expansion are documented from across the African continent. While European nations gained wealth and power, local African populations’ basic human rights and freedoms, cultures, livelihoods and lands were denied, exploited and stolen.

If you did not read this short research brief in the Prelim Engagement, you may want to do so now to learn more about lasting effects of colonial medical practices on (dis)trust of medical intervention today:

As we move through the course we will ask you to recall these historical injustices as determinants of health, including the effects of intergenerational trauma on health outcomes for generations after the occurrence of the events themselves.

In arguably the most gruesome show of disregard for human life in the name of power and profits, the Belgian Congo stands as an example of how the poverty, underdevelopment and poor health outcomes observed in many former colonies today began with exploitation in the late 19th century.

Watch the short video below to learn more about colonial histories and relationships specific to the current-day Democratic Republic of the Congo and the country’s former colonizer, Belgium.

In the following video clip, Nigerian-born culinary scholar and chef Ozoz Sokoh explores some important themes related to colonization, the re-writing / whitewashing of history and legacies of colonialism in Africa and the world today.

Whitewashing is to alter something, [including history], in a way that favors, features, or caters to white people such as to portray (the past) in a way that increases the prominence, relevance, or impact of white people and minimizes or misrepresents that of nonwhite people.

(Merriam-Webster, n.d.)

Tropical Medicine & Colonial Expansion

In the years following the Berlin Conference, colonizing powers had an ongoing need to keep both their agents and their native workers healthy enough to work. Geographic areas or regions in Africa and Asia of a particular climate or latitude were loosely referred to as ‘the Tropics’ by westerners. The particular diseases affecting settler colonists and native peoples in ‘the Tropics’ such as, for example, malaria and yellow fever, became referred to as Tropical diseases. A combined lack of understanding of these diseases, advancements in germ theory from scientists like Louis Pasteur that proved diseases were caused by microbes and, therefore, could be prevented, and the ongoing drive for profit-making in the colonies resulted in the formalization of colonial medicine into what is known as the field of tropical medicine.

The new science of tropical medicine [in the late 19th century] suggested that one could control the damaging economic effects of epidemic disease by fighting its nonhuman vectors (such as the Anopheles mosquito [which transmits malaria to and between humans]) without providing direct curative services to native populations. This logic resonated within institutions of colonial medicine that tended to deal with native subjects as populations rather than as individuals.

(Greene et al., 2013)

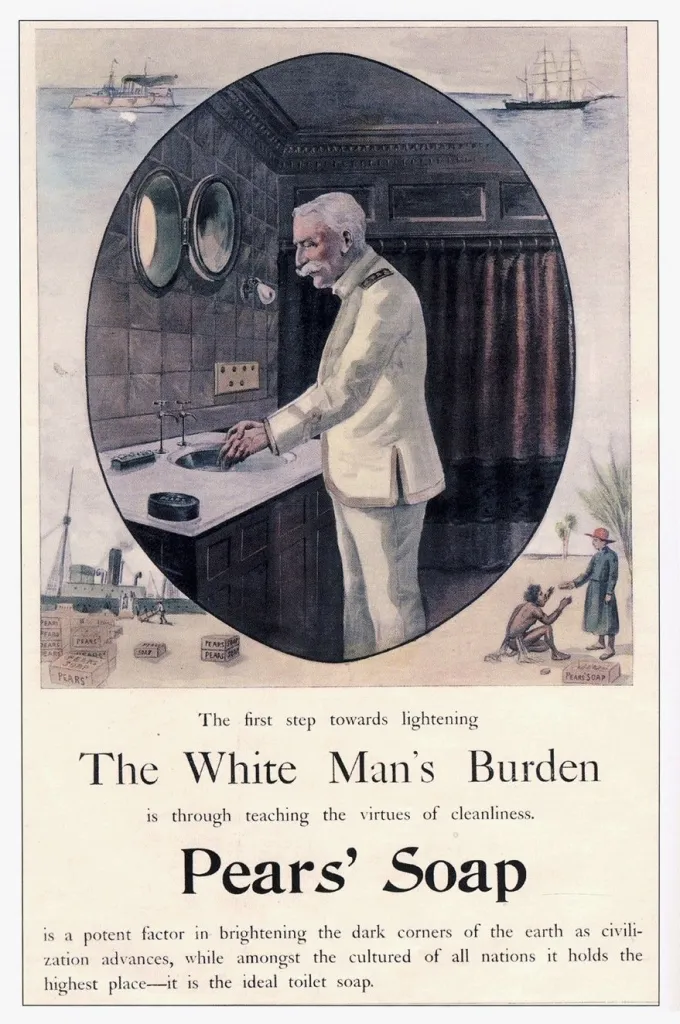

The emergence of tropical medicine as a distinct field led to the establishment of schools of tropical medicine in the United Kingdom (London and Liverpool) and elsewhere in Europe and around the world. The field of tropical medicine, and the institutions teaching, promoting and facilitating work in the field, were founded on racialized and racist ideologies.

The science of tropical medicine, far from extinguishing a racialized language of the ‘disease native,’ enabled it…a moral language of health, hygiene and the “civilizing process” suffused colonial [and, thereby, tropical medicine] discourse…In stories, magazine articles and advertisements, nonwhite colonial subjects were depicted as childlike or, worse, as part of the local flora and fauna that made the tropics a risky place for white bodies.

(Greene et al., 2013)

Colonialism and, therefore, tropical medical interventions including those interventions such as examinations, injections and procedures forced upon native populations in gross violation of human rights were justified in the name of the ‘civilizing process,’ including the moral and racial superiority of white populations.

(Greene et al., 2013)

Advertisement text reads: “The first step towards lightening the White Man’s Burden is through teaching the virtues of cleanliness. Pears’ Soap is a potent factor in brightening the dark corners of the earth as civilisation advances, while amongst the cultured of all nations it holds the highest place – it is the ideal toilet soap.”

Source: http://www.danceshistoricalmiscellany.com/toilet-soap-cleanliness-imperialism/

Today, the field of tropical medicine still exists and is taught by medical, public and global health institutions around the world. While these institutions have, in theory, moved far away from the racialized, racist, ‘civilizing’ missions under which they were founded and many engage in scholarly work which looks to dismantle the legacies of their colonial past, the colonial past lingers. For example, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical medicine, founded in 1893 as a colonial tropical medicine institution, maintains its original name. “Hygiene” is a direct reference to the original colonial aims of improving the hygienic practices of native populations and, therefore, civilizing them.

Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas is another institution of higher education that maintains a National School of Tropical Medicine today. See this medical school’s definition of tropical medicine and the field’s role in Global Health in 2021 below. Note, however, that even in defining Tropical medicine in relation to ‘diseases of poverty,’ there is no mention of colonial histories as either precursors to this field of study or as a major contributing factor to poverty in low- and middle-income countries (referred to here as ‘developing’ countries).

What is Tropical Medicine? [Baylor College of Medicine, 2021)

Tropical medicine is the study of the world’s major tropical diseases and related conditions, which include a group of 17 neglected tropical diseases (sometimes referred to as ‘NTDs’) such as hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, river blindness, elephantiasis, trachoma, Chagas disease, Buruli ulcer, and leishmaniasis, as well as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. The field also includes related disorders in malnutrition and even some non-communicable diseases.

Diseases of Poverty

First and foremost tropical diseases are diseases of poverty. They are the most common afflictions of the “bottom billion” the 1.3 billion people who live below the World Bank poverty level. Although tropical diseases are generally thought of as exclusively occurring in developing countries, new evidence indicates that the poor living in wealthy countries also are affected by tropical diseases. For instance, in the United States, tropical diseases such as Chagas disease, cysticercosis, dengue, toxocariasis, and West Nile virus infection are now widespread.

Tropical Medicine’s Role

Tropical medicine is an important component of global health, but it is more focused on the specific tropical infections that occur in resource poor settings, with detailed emphasis on the pathogens, their vectors, how they are transmitted (their epidemiology), their treatment and prevention, and even how to develop new control tools to combat tropical diseases, including new drugs, insecticides, diagnostics, and vaccines.

(Baylor College of Medicine, 2021)

African Independence, neocolonialism & international health

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, colonialism in Africa continued exploitative labor and health practices. We do not have the time in this course to fully explore the depth and breadth of these violent infractions, but within less than a century European powers had managed to extract immense amounts of wealth from the African continent to fuel their own economic growth and development at the cost of many lives. The activism of native Africans and a number of global human rights campaigns ended the most brutal practices seen throughout the 19th century. However, native populations in colonies around the world were still denied their full rights, had no say in the governments or laws that ruled them, were kept from educational and economic opportunities and lived in extreme poverty and poor health.

Native Africans’ movements for independence from colonial powers gained momentum throughout the first half of the 20th century. World War II also marked a shift in global politics as the world — but Europe especially — recovered from the devastating effects and aftermath of the war. In the last years of the war and years immediately following the war, the first international institutions to promote global peace, well-being and economic and social development were established. These included the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (1944), the United Nations (1945) and the World Health Organization (1948).

These institutions were founded in the hope that international cooperation was the way forward to maintain world peace and avoid another devastating world war, but also promote the economic and health development of poor populations around the world (Black, 2007). The United States, Europe and the Soviet Union worked together to establish these post-war international institutions but the divisions between democratic and communist ideologies were too great. By the 1950s the Cold War was in full swing and cooperation between the United States and Western Europe and the Soviet Union and its allies fell apart.

For a reminder on the establishment, missions and work of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank watch this video you screened in Section 1.3:

A number of factors converged mid-century and led to a wave of African nations’ independence from colonial rule. In 1960 alone, 17 African countries gained independence as autonomous nations (Black, 2007). Thanks to the discriminatory policies of the colonists, many nations began their independence journeys with a largely illiterate population suffering from undernutrition and other health challenges. Newly independent African countries were, from the perspectives of America and the Soviet Union, potential allies and it was imperative that each bloc expand its political and economic influence around the world.

One way of doing this was through promoting and facilitating economic development in poor countries abroad. In 1960, US President John F. Kennedy established a number of US-funded international programs focused on economic development and increasing US diplomacy around the world; these included the Peace Corps, the Alliance for Progress and Food for Peace (Black 2007).

To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves…If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it can never serve the few who are rich.

(United States President John F Kennedy, 1960, (in Black, 2007))

While early international development efforts were very much tied to Cold War politics, Black (2007:18) also states that:

“Whatever part was played by self-interest, there was also a heartfelt political commitment to the crusade [to help poor nations]…it echoed powerfully across the whole political spectrum, but especially among the radical young. The rich nations should help the poor not only to gain their allegiance, but – as Kennedy said – ‘because it is right.’”

It is significant to note, however, that as President Kennedy’s words illustrate there is no explicit mention of the root causes of the ‘mass misery’ experienced by ‘peoples in huts and villages of half the globe.’ The failure of Presdient Kennedy’s comments to mention or recognize the role that the transatlantic slave trade or even the previous century of colonial exploitation played in creating those conditions of ‘mass misery’ is typcial of most literature of the time. According to President Kennedy’s comments, responsibility lies with native peoples who simply need ‘help to help themselves’ out of poverty. There is no mention of returning, for example, even a fraction of the wealth taken from the African continent which helped fuel American and European economic growth. Though this is changing, even in today’s literature there is relatively little conversation about who is responsible for the creation and continuation of global inequities and disparities.

This mid-century focus on health and development of ‘Third’ world nations by ‘First’ (western, democratic, capitalist) and ‘Second’ (eastern, Soviet, communist) world nations marked the definitive beginning of international Health.

For decades, international health was the term used for health work abroad, with a geographic focus on developing [low- and middle-income] countries and often with a content of infectious and tropical diseases, water and sanitation, malnutrition, and maternal and child health. Many academic departments and organisations still use this term, but include a broader range of subjects such as chronic diseases, injuries, and health systems. The Global Health Education Consortium defines international health as a subspecialty that “relates more to health practices, policies and systems…and stresses more the differences between countries than their commonalities”. Other research groups define international health as limited exclusively to the diseases of the developing world.

(Koplan et al., 2009)

Think back to our definitions of Global Health from Section 1.1: What is Global Health? Do you notice any significant differences between the definition of International Health and our understanding of Global Health? Anything missing? See Table 1. below for a comparison between International Health, Global Health and Public Health.

A number of differences should stand out to you between the fields of Global and International Health. Perhaps the most notable, however, are the emphasis placed on the “differences between countries rather than their commonalities” (Koplan et al 2009) and the fact that equity in health access and outcomes is not a central feature of International Health.

While Global Health puts forth a vision of common global challenges and shared responsibility for achieving health equity for all, International health sets up a more dichotomous world. An ‘us’ (high income countries) versus ‘them’ (low- and middle-income countries) mentality emerges. This divided view of the world replicates in rather uncomfortable ways the power dynamics of the colonial era — ‘we’ the high-income countries, the experts, have something to offer ‘them’ the low- and middle-income countries. And, again, no acknowledgement as to why these inequities between high-, middle- and low-income countries exist and who should be held responsible for reducing them.

The Alma Ata Declaration, Primary Health Care & Health for All

Let’s get back to history, shall we?

In the decades immediately following the end of World War II, funds from high-income countries, especially the United States, flowed to low-income countries to improve economic and health development. Despite global optimism and commitment, modest improvements in economic and health outcomes in low-income countries had not largely trickled down to the masses (Black, 2007). Global leaders began asking why years of financial and political efforts to reduce poverty and improve health outcomes had not resulted in significant gains, leading to discussions about alternatives to development models.

A number of countries, some newly-independent, linked poor health with social inequities and a lack of economic development. So, they pushed ahead with health-centered initiatives, including access to healthcare for all citizens, as a way to achieve economic growth. Countries such as Tanzania, Mozambique, Cuba and China prioritized the principles of primary health care to promote the equitable distribution of health and well-being to all of its citizens (Usdin, 2007).

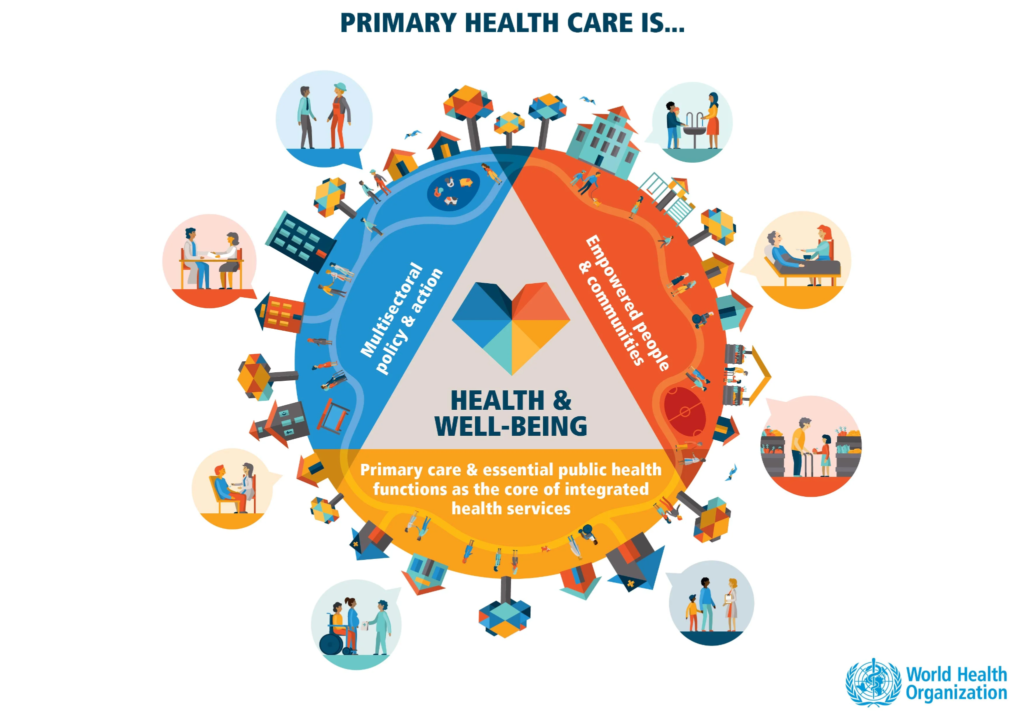

Primary health care is referenced often in Public and Global Health and we will reference it again throughout the course. While health services are part of primary health care, in Public and Global Health primary health care does not refer only to health services themselves, such as visiting a doctor or having an operation. Rather, primary health care is a multi-part, holistic approach to ensuring equitable health and well-being; at the time it was a “revolutionary concept with social justice at its core” (Usdin, 2007:19) and included offering preventative, curative and rehabilitative health services tailored to communities’ needs intertwined with a public health approach to well-being.

PHC is a whole-of-society approach to health that aims at ensuring the highest possible level of health and well-being and their equitable distribution by focusing on people’s needs and as early as possible along the continuum from health promotion and disease prevention to treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care, and as close as feasible to people’s everyday environment.

(WHO and UNICEF, 2018)

Watch this short clip to understand what a primary health care approach to health means.

Unfortunately, many countries had not or were not able to prioritize this holistic approach to health. Therefore, health outcomes in these countries in the decades following colonial independence, such as life expectancy, infant, child and maternal mortality, were very poor.

However, the world was still inspired and hopeful. In a wave of optimism that primary health care, equity and health for all could become a global reality, one of the most celebrated events in Public and Global Health history occurred in 1978 in Alma Ata, Kazakhstan.

The Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 was a coming together of countries from around the world — amidst the tensions of the Cold War, remember — to boldly and unquestioningly declare that health was a human right and primary health care should be ensured for all people by the year 2000. Countries which signed onto the Declaration included — surprise, surprise! — the United States of America.

Watch this short video to learn more about this historic and celebrated Global Health moment.

All countries should cooperate in a spirit of partnership and service to ensure primary health care for all people

(Alma Ata Declaration, 1978)

If you want to read the original text of the relatively short but historic Alma Ata Declaration of 1978 you can find it here.

When you reflect on the principles of Alma Ata, think back to our discussions about the social and structural determinants of health and the bi-directional relationships between wealth, education, intellectual development, economic productivity and health. As described by Greene et al. (2013):

“The [Alma Ata] declaration frames health as an avenue for social and economic development. Delegates at Alma-Ata argued that expanding access to primary health care services would improve education and nutrition, thereby bolstering the work force. They conceived of health as an end in itself and also as a tool for development” (80).

These principles and a comprehensive understanding of health are illustrated in the declaration’s definition of primary health care which includes:

Education concerning prevailing health problems and the methods of preventing and controlling them; promotion of food supply and proper nutrition; an adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation; maternal and child health care including family planning; immunization against the major infectious diseases; prevention and control of locally endemic diseases; appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries’ and provision of essential drugs (Alma Ata Declaration (1978) as quoted in Greene et al 2013)

Structural Adjustment Programs, Selective Primary Health Care & Neocolonialism

Healthcare for all? International collaboration? Global equity and justice? Solutions to health challenges informed by local conditions and contexts?

That sounds amazing!

A new era!

So, what happened!?

Well, the 1980s happened.

Before we talk about the 1980s, though, let’s take it back to the 1970s.

We discussed how colonial powers vacated Africa after about a century of actively keeping most Africans outside of educational, economic, legal and political systems. Of all of the phenomenal wealth generated during the colonization of Africa, very little of that wealth stayed on the continent itself— most of it flowed directly or indirectly into the financial markets of European and American governments and economies. Newly independent African countries had some infrastructure, but most of that infrastructure was organized around wealth extraction — existing high production agriculture, roads, train lines, electricity, health services and sanitation systems served mostly white colonists or Africans living in built up urban areas, and the industries and plantations that were producing their wealth. Existing infrastructure was not largely serving the everyday needs of most Africans across the continent, especially those living in rural areas. Newly independent African nations needed financial resources to improve education and health services, infrastructure and economic opportunities in urban areas and expand those services and opportunities to rural areas. Governments needed funds to jumpstart their economies to benefit their populations, rather than colonial powers.

This is where international financial institutions really come into play. In the 1970s, oil producing countries’ economies ‘boomed’ after they increased the global prices of oil exports and oil-dependent countries in the global north had no choice but to pay up (Cavanaugh and Mander, 2003). Banks in the global north became “awash” with cash from this influx of financial capital (Cavanaugh and Mander, 2003) — and banks love to make more money!

How do they do that?

Through loans. With interest.

Who needed cash loans in the 1970s? Well, a lot of people — but those governments of newly independent countries were especially in need of cash to develop their economies, educational, health and political systems. So there the money went — most low-income countries in Africa, but also countries across Asia and Latin America, welcomed loans from international financial institutions to dive into economic and social development.

It seemed like the market economy might take care of it all — until it quickly did not. By the mid-1970s a global economic crisis was looming.

| High oil prices in the mid-1970s, followed by soaring interest rates, caused an economic contraction throughout the developed world [high income countries], lowering demand for products exported by the developing world [low income countries]. The governments of the developing countries…had taken out significant loans…and were now squeezed by growing debt service on the one hand and declining demand for their exports on the other. (Greene et al 2013: 86). |

August 18, 1982 was a pivotal day for the world economy and international health and development for years to come: the government of Mexico defaulted on its loans, “signaling systemic debt problems across the developing world” (Greene et al 2013:87). Other low- and middle-income countries followed. International financial panic ensued, investments were pulled from low- and middle-income countries and financial institutions looked to western governments, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to fix the situation — and quickly (Greene et al, 2013).

In the years leading up to this crisis, some countries in the western world experienced a shift in politics. In 1979 Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and in 1980 Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States. The Reagan-Thatcher years resulted in a wave of both domestic and international socially and fiscally conservative policies, with the United Kingdom and the United States leading the movement on the international stage.

SOURCE: Reagan Library from https://www.theaustralian.com.au/inquirer/why-thatcher-and-reagan-should-still-matter-to-us-all/news-story/61698eeca65accbb7bf77dbc5521e6e0

The particular set of economic policies the Reagan and Thatcher administrations recommended to deal with the debt crisis in African, Latin American and Asian countries became known as the Washington Consensus.

| Economist John Williamson coined the term “Washington Consensus” in 1989, in reference to a set of 10 market-oriented policies that were popular among Washington-based policy institutions, as policy prescriptions for improving economic performance in Latin American countries. These policies centered around fiscal discipline, market-oriented domestic reforms, and openness to trade and investment. In African countries, the Washington Consensus inspired market-based reforms prescribed by international financial institutions (IFIs) like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), under “structural adjustment programs” (SAP), often as prerequisites for financial assistance. (Archibong, Sangafowa Coulibaly and Okonjo-Iweala, 2021) |

The Washington Consensus can be summarized as ‘Stabilize, Liberalize, Privatize’ (Greene et al., 2013: 87) — a reliance on the market economy and the privatization of public services to get the international debt crisis under control and spark social and economic development in low-income countries.

Here we enter what many Global Health and development historians, economists and social scientists consider the epitome of neocolonialism in the 20th century: international financial policy that would, some scholars say, go on to ensure that low-income countries would stay under the control of high-income countries for the rest of the 20th century and, even, today.

Now that you have a bit more context and history, let’s revisit the definitions of neocolonialism we touched on earlier in this section.

Neocolonialism is the use of economic, political, cultural, or other pressures to control or influence other countries, especially former dependencies.

(OED, 2021)

Neocolonialism is the control of less-developed countries by developed countries through indirect means. The term neocolonialism was first used after World War II to refer to the continuing dependence of former colonies on foreign countries, but its meaning soon broadened to apply, more generally, to places where the power of developed countries was used to produce a colonial-like exploitation—for instance, in Latin America, where direct foreign rule had ended in the early 19th century. The term is now an unambiguously negative one that is widely used to refer to a form of global power in which transnational corporations and global and multilateral institutions combine to perpetuate colonial forms of exploitation of developing countries. Neocolonialism has been broadly understood as a further development of capitalism that enables capitalist powers (both nations and corporations) to dominate subject nations through the operations of international capitalism rather than by means of direct rule.

(Halperin, n.d.)

→ In the early 1980s, the International Monetary Fund and World Bank expanded lending programs to low-income countries as one response to the debt crisis. Basically, here are some more loans to help your economic and social development — and to help you pay back those other loans you still owe. But, this time there was a catch. In order to accept these new loans, countries had to agree to very specific conditions known as structural adjustment programs or SAPs.

A group of international economists in the early 1980s, specifically those directing policy at the World Bank and IMF, believed that “excessive government intervention had driven sub-Saharan African’s economic stagnation” in the 20 or so years following independence (Greene et al., 2013:87).

This fiscally conservative principle was woven throughout SAPs.

In order to receive new loans, governments had to agree to structural adjustment programs (SAPs).

SAPs required governments to:

• Cut government spending on education, health care, the environment, and price subsidies for basic necessities

such as food grains and cooking oils;

• Devalue the national currency and increase exports by

accelerating the plunder of natural resources, reducing

real wages, and subsidizing export-oriented

foreign investments;

• Liberalize (open) financial markets to attract

speculative short-term portfolio investments

that create enormous financial

instability and foreign liabilities

while serving little, if any, useful purpose;

• Eliminate tariffs and other controls on

imports, thereby increasing the import

of consumer goods purchased with borrowed

foreign exchange, undermining

local industry and agricultural producers

unable to compete with cheap imports,

increasing the strain on foreign exchange accounts,

and deepening external indebtedness.

(Cavanagh and Mander, 2003)

As a note, high-income countries in no way, shape or form were required to follow any such principles or restrictions. In fact, it is almost inconceivable to think of countries like the United Kingdom or the United States agreeing to, for example, “eliminate tariffs and other controls on imports, thereby increasing the import of consumer goods…” which would then undermine nationally-produced goods and services.

So, while low-income countries were forced to watch cheap imports such as agricultural products and consumer goods flood their markets, high-income countries continued to protect the prices of their nationally-produced products. These policies had and continued to have a direct impact on health. For an example, see the case study to the left.

Case study [optional] Effects of international economic policy on food availability and health: The Rice Market in Senegal

We know the prices of locally-produced agriculture and goods and the generation of national income have effects on health. Let’s focus here, though, on perhaps the most direct impact of SAPs on access to health care in low- and middle-income countries:

[SAPs] forced countries to cut government spending on education, health care, [and] the environment.

(Cavanagh and Mander, 2003)

In the years following colonial independence, many new African governments made health and education services free or very low cost for citizens. Whereas many African governments — in line with the foundational principles of Alma Ata, even before Alma Ata occurred — treated access to healthcare as a human right, the Washington Consensus and the SAPs formulated by the IMF and World Bank did not.

| SAPs emphasized market-oriented policy reforms and a diminished role for the state as a direct service provider. In line with these prescriptions, the World Bank promoted a new vision of health reform, resing on the notion that health care is a commodity — not a right — that can be efficiently allocated by the [economic] market…The bank also promoted privatizing public health services: To help the poor improve their household environments, governments can provide a regulatory and administrative framework within which efficient and accountable providers (often in the private sector) have an incentive to offer households the services they want and are willing to pay for, including water supply, sanitation, garbage collection…[The government] can also improve the use of public resources by eliminating widespread subsidies for water and sanitation that benefit the middle class. (Greene et al., 2013: 88 from a 1993 World Bank report; bold type added for emphasis) |

OK, so those are a lot of words. What did — and does this continue — to mean for the average African family?

Water, sanitation and garbage collection, education, agricultural and food products were once affordable (or free) because of government subsidies. Access to these services and products, all of which we know are social or structural determinants of health, was considered a right. Under SAPs, however, world financial institutions required low-income governments to agree to the above conditions (as outlined by Cavanaugh and Mander (2003) and Greene et al. (2013)) in order to receive loans to pay back previous loans and continue to invest in economic and social development projects (ie infrastructure such as hydroelectric dams).

Essentially, services and goods which at one time were considered rights, were then under SAPs considered commodities — or things to be bought and sold.

The economic theory was that people would “buy the services they wanted and were willing to pay for” and the money gained by user fees charged to use, for example, health services would go to fund the health system. The health system and other essential services would operate as businesses and the government would no longer need to subsidize or pay for these services.

The problem was, who doesn’t want — or need — goods and services such as affordable food, electricity, clean water, education and medical care? Given the extreme poverty of many African households during these years, many households could not afford the user fees you needed to pay to access health services, water or education.

So what happened?

People simply didn’t use these services. Population health outcomes suffered. Health facilities and health systems received little to no government financial support and few people could afford to pay for health services. So, health workers lost pay, health facilities fell into disrepair and the quality of health services declined.

Think back, now, to that historic moment at Alma Ata. Can you see how world economic policies almost immediately after the declaration of 1978 left no room for a vision of health care for all by the year 2000?

The following video offers a summary of these points with specific perspectives from a former government minister from Nigeria:

All the while, low-income countries continued to accrue interest on their debt, and continued to borrow — in other words, their debt grew. With so much debt and interest owed to international financial institutions, it essentially became impossible for countries to ever pay back their loans. Plus, money used to pay back loans was, of course, not going to the flailing health, educational and social services so badly needed to improve health and development outcomes for African populations.

The reality of the debt crisis in Africa

In 1980, the total external debt of all developing countries was $609 billion; in 2001, after 20 years of structural adjustment, it totalled $2.4 trillion. In 2001, sub-Saharan Africa paid $3.6 billion more in debt service than it received in new long-term loans and credits. Africa spends about four times more on debt-service payments than it does on health care. (Cavanaugh and Mander, 2003; bold type added for emphasis).

Nigeria, for example, borrowed $5 billion in 1986, paid back $16 billion but absurdly now [in 2007] owes $32 billion. Across Africa, where one in every two children of primary school age is not in school [in 2007], governments transfer four times more to Northern creditors in debt repayments than they spend on the health and education of their citizens.

Even Argentina, which followed prescriptions to the T, and appeared to be doing well in the process, experienced a total meltdown in 2001 when ‘conditions sparked off massive social unrest and the country defaulted on $155 billion of its foreign debt (Usdin, 2007).

You can now see how SAPs especially put so many nations’ autonomy back into the hands of their former colonizers. While colonialism may have ended, neocolonialism ensured that inequitable global power dynamics remained entrenched.

So, what were the tangible effects of SAPs on the lives of already poor people?

It is fair to say that SAPs alone were not responsible for the stagnated economic development, political crises and poor health outcomes seen in low-income countries around the world. A number of factors intersected at this complex juncture of history, including global economic financial and political crises. However, the failure of SAPs to ‘right’ the ‘wrongs’ of protectionist governments and the prioritization of social welfare priorities could not be denied.

| With dozens of countries under ‘adjustment’ for well over a decade, even the World Bank had to acknowledge that it was hard to find a handful of success stories. In most cases, structural adjustment caused economies to fall into a hole wherein low investment, reduced social spending, reduced consumption, and low output interacted to create a vicious cycle of decline and stagnation rather than a virtuous cycle of grown, rising employment and rising investment, as originally envisaged by the World Bank-IMF theory. (Cavanaugh and Mander, 2003) |

| It is difficult to separate the effects of SAPs on health from the economic recessions that preceded their imposition. But in the 1980s, during the period when SAPs intensified, there are clear relationships between slowing of gains in infant mortality rates and increasing debt as well as other negative health impacts. In Zambia for example the proportion of hospital deaths related to malnutrition, from 1980 to 1984, increased two-fold in children under 5. In the instances when SAPs led to growth, wealth accrued to an elite and in most instances did not lead to social development. Despite the fact that total world income increased by an average of 2.5 per cent annually, the number of people living in poverty increased by almost 100 million people. Inequities in the 1990s reached unprecedented proportions. (Usdin, 2007:28-29) |

An entire body of research in the last decades explores the effects of SAPs, including effects on health in low-income countries. As early as 1987, UNICEF identified and publicly criticized the negative effects of SAPs on children and mothers (Gloyd, 2004). Again, while we can say a number of factors have led us to the extreme economic and health disparities we see today the general agreement, even from the financial institutions which so ardently pushed these economic reforms, is that SAPs were detrimental to economic, health and social development outcomes.

Post-SAPs: what then?

As the year 2000 rolled around the world could no longer hide from the detrimental effects of the approaches to health and development of the previous 50 years. Backlash against these policies and institutions took many forms including citizen protests around the world, debates in national governments including the United States Congress and calls for debt relief (Cavanagh and Mander, 2003).

In 2000, Kofi Annan, then-Secretary General of the United Nations, drew attention to the ongoing debt crisis in Africa by highlighting that governments were still spending up to 40% of country revenue on debt payments (Gloyd, 2004). Debt forgiveness programs facilitated by the IMF and World Bank were launched in the mid-1990s however these programs still required countries that qualified to follow SAPs for some years before some debt would be forgiven and the IMF and World Bank were still responsible for setting the rules and road to forgiveness (Gloyd, 2004). While there were some notable improvements for countries whose debt was forgiven, debt forgiveness programs far from solved the underlying structural problems as illustrated in the case study below of Mozambique.

Case study: Debt forgiveness in Mozambique

After Mozambique qualified [for debt forgiveness], its debt dropped only slightly. After entering the second round [of debt forgiveness], Mozambique received a decrease in its debt service payment from $114 million per year to $55 million per year. This payment remained, however, substantially greater than the government’s contribution of $42 million to the health sector. Nevertheless, the reduction did permit the government of Mozambique to increase its health expenditures to $7.50 per capita [per person] per year, up from only $4 three years earlier (Gloyd, 2004:53).

Once SAPs were abandoned as the cornerstone of global financial institutions’ development policy for low-income countries, some scholars argued that global economic policy and institutions were “left adrift, with the rhetoric and broad goals of reducing poverty but without an innovative macroeconomic approach” to advancing the health and development of low-income countries and reducing economic and health disparities (Cavanagh and Mander, 2003).

While both the World Bank and IMF have significantly shifted their rhetoric, policies and actions towards poverty reduction in recent years and fund (loan-free) a number of health and development projects around the world, many still do not feel it is enough. They believe that despite moves away from SAPs as they were envisioned some 40 years ago, neocolonialism and the exploitation and control of low- and middle-income countries by high-income countries has simply taken other forms.

| Today, the work of the Bank is currently framed by its twin goals, established in 2013: “eliminating extreme poverty by 2030 and boosting shared prosperity.” These are primarily targeted in principle through: direct lending for development projects; direct budget support to governments (also known as Development Policy Financing [DPF]); financial support to the private sector, including financial intermediaries (FI); and via guarantees for large-scale development. The current stated aims of the Fund are promoting international fiscal and monetary cooperation, securing international financial stability, facilitating international trade, and promoting high employment and sustainable economic growth. It aims to do so by providing loan programmes to states with balance of payments problems, as well as policy advice through either technical assistance or bilateral and multilateral macroeconomic surveillance. There is no question that the IMF and World Bank continue to be amongst the most relevant and significant powerful norm-setters, convenors, knowledge-holders and influencers of the international development and financial landscape. This Inside the Institutions [optional reading for students] sets-out some of the most common criticisms of the World Bank and IMF under three broad lenses: democratic governance, human rights and the environment (Bretton Woods Project, 2019). |

Pathways forward: Decolonization, Indigenization & a Re-imagining of Global Health

In this section we have explored the intersecting histories of colonialism, neocolonialism and health. We discussed structural and historical determinants of global poverty and health, and in great part answered the question: why are poor countries poor?

We traced the origins of the field of Global Health, beginning with colonial and tropical medicine and, more recently, the perspectives driving International Health. We distinguished the field of Global Health from International Health. Global Health emphasizes commonalities and shared challenges of populations around the world, while International Health focuses on differences between places and the things that distinguish populations. Global Health also has at its core a drive toward health equity and justice.

While these intersecting histories we have explored are in the past — some even centuries in the past — the most significant message to take from this section is that historical legacies related to Global Health very much remain in the present. The individuals, organizations and institutions that work in the field of Global Health must recognize and take tangible actions to dismantle the lingering effects of the field’s racist, oppressive and violent roots. Unequal power dynamics continue to define the field of Global Health. In fact, the entire field of Global Health exists to undo inequities that high income countries created but these histories are often not acknowledged. And, most of us working in this field are products of systems that still breed inequity, injustice and racism. The legacies of oppressive, racist and violent medical practices during colonialism have not disappeared from the collective memories of the populations the field aims to serve, nor have they stopped affecting our relationships with partners and colleagues in low- and middle-income contexts.

While Global Health by definition promotes equity and recognizing common humanity and strengths, the field generally operates under an ‘us’ (‘experts’, often white, from high income countries) helping ‘them’ (Black, Indigenous and people of color who need our help) framework, thereby replicating unequal colonial power dynamics. One way this particular colonial legacy has been described is the white savior complex.

SOURCE: Teju, Cole. (2012). The White Savior Industrial Complex. The Atlantic https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/

| White savior complex is a term that’s used to describe white people who consider themselves wonderful helpers to Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) — but they “help” for the wrong reasons (and sometimes end up doing more to hurt than help). Keep in mind that this doesn’t refer to all white people. White savior complex, sometimes called white savior syndrome or white saviorism, refers to those who work from the assumption that they know best what BIPOC folks need. They believe it’s their responsibility to support and uplift communities of color — in their own country or somewhere else — because people of color lack the resources, willpower, and intelligence to do it themselves. In short, white saviors consider themselves superior, whether they realize it or not. They swoop in to “make a difference” without stopping to consider whether that difference might not, in fact, have more negative effects than positive ones. White saviors often speak passionately about their desire to “do the right thing.” Yet their actions usually involve very little input from the people they’re attempting to help. Their intentions may be noble — many white saviors believe their actions challenge the white supremacy and racism so deeply threaded into American society. In reality, though, white saviorism tends to emphasize inequality, because it continues to center the actions of white people while ignoring (or even invalidating) the experiences of those they’re claiming to help. (Raypole, 2021) |

All of these historical and contemporary truths and power dynamics must be recognized, discussed, accounted for and shifted in tangible ways if the field of Global Health is to truly undo historical wrongs and achieve global health equity. Two (of many) frameworks that have been used to understand what individuals, organizations and institutions can do to this end, especially to undo the deeply-rooted and ongoing negative effects of colonialism and white saviorism, are decolonization and Indigenization.

There are no standard or uniform definitions of these concepts and frameworks; rather, decolonization and Indigenization are better described as ongoing conversations and processes that should lead to tangible action (Attas, n.d.). Importantly, the burden of carrying out tangible action to break down inequities and repair historic wrongs within the field of Global Health and, more broadly, in the world and communities around us should not fall to BIPOC and other people who have been systematically marginalized. Rather, people historically or currently considered colonizers should lead efforts to transfer power — but always guided by the experiences, knowledge, skills and needs of BIPOC and other people who have been systematically marginalized.

Decolonization of global health would mean to “remove all forms of supremacy within all spaces of global health practice, within countries, between countries, and at the global level. Supremacy is not restricted to White supremacy or male domination. It concerns what happens not only between people from HICs and LMICs but also what happens between groups and individuals within HICs and within LMICs

…

Will global health survive its decolonization? Well, if the future of global health is more of the same with some cosmetic changes to disguise supremacy, it would have failed. But if the future is a radical transformation, then global health would be unrecognizable. We may even have to give it a new name. The goal of global health should not be to survive its decolonization, but to rise up and live up to the pressing demands of its mission.” (Abimbola & Pai, 2020).

For an excellent, but brief, commentary and vision on decolonizing Global Health see: Will global health survive its decolonisation? By Abimbola, S and Madhukar, P (2020)

| Indigenization is when “power, dominance and control are rebalanced and returned to Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous ways of knowing and doing are perceived, presented, and practiced as equal to Western ways of knowing and doing. Indigenization moves beyond tokenistic gestures of recognition or inclusion to meaningfully change practices and structures. Examples of Indigenization in education could include the inclusion of Indigenous readings, adoption of Indigenous learning approaches in the classroom. For non-Indigenous people, there can be a fine line between Indigenization and cultural appropriation and it is important to seek appropriate guidance while recognizing that guidance can come from many sources” (Attas, n.d.). |

One aim of this section is, admittedly, to complicate rather than simplify our understanding of the field of Global Health — and all of our places in it. While it can be daunting and discouraging to encounter loaded and often horrific histories in a field that aims to achieve equity, it is also invigorating to imagine what a new way forward might look like and how each of us might contribute to acknowledging history while reshaping lived realities.

As we move through the rest of this course, we encourage you to refer back to these first foundational sections and push yourself, your classmates and your instructors to see Global Health challenges and power dynamics through the lenses of social, structural and historical determinants of health.

References

References Section 1.5 History of Global Health

- Illinois Department of Public Health. (n.d.) Understanding Social Determinants of Health. https://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/life-stages-populations/infant-mortality/toolkit/understanding-sdoh

- Galea, S. (2017, March 12). History as a Determinant of Health. Boston University School of Public Health. https://www.bu.edu/sph/news/articles/2017/history-as-a-determinant-of-health

- Adi, H. (2012, October 5). Africa and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/africa_article_01.shtml

- Farmer in Kidder, T. (2014). Mountains beyond mountains: The quest of Dr. Paul farmer, a man who would cure the world. Ember.

- Greene et al (2013) Chapter 3: Colonial Medicine and its Legacies in Mountains Beyond Mountains.

- Lowes, S. & Montero, E. (2018, February 25). The Legacy of Colonial Medicine in Central Africa. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/emontero/files/lowes_montero_colonialmedicine.pdf

- Rodney, W., & Davis, A. (2018). Forward. In How Europe underdeveloped Africa (2nd ed.). essay, Verso.

- Oxford English Dictionary. (2021). https://www.google.com/search?q=neocolonialism+definition&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS800US800&oq=neocolonialism&aqs=chrome.1.69i57j0i512l2j46i512l3j0i512j69i61.3965j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

- Halperin, Sandra. (n.d.) Neocolonialism. Britanica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/neocolonialism

- Rosenberg, M. (2019). The Berlin Conference to Divide Africa: The Colonization of the Continent by European Powers. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/berlin-conference-1884-1885-divide-africa-1433556

- Sokoh, Ozoz. (2021). Coast to Coast: From West Africa to the World. https://vimeo.com/488916475

- World Health Organization. (2021). History. https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/history

- Black, Maggie. (2007). The No-nonsense Guide for International Development. New Internationalist Publications, Limited.

- Koplan et al. (2009). Towards a Common Definition of Global Health.

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Whitewash. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/whitewash

- Usdin, Sheeren. (2007). The No-nonsense Guide to World Health. New Internationalist Publications, Limited.

- World Health Organization and UNICEF. (2018). A vision for primary health care in the 21st century: Towards UHC and the SDGs. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care

- Gloyd, Steve. (2004). Chapter 4: SAP-ping the poor: The Impact of Structural Adjustment Programs. In Fort, M, Mercer, M, and Gish, O. Sickness and Wealth: The Corporate Assault on Global Health.

- Thomson, M., Kentikelenis, A. & Stubbs, T. Structural adjustment programmes adversely affect vulnerable populations: a systematic-narrative review of their effect on child and maternal health. Public Health Rev 38, 13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0059-2

- Brettonwoods Project. (2019). What are the main criticisms of the World Bank and IMF? Bretton Woods Project. https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2019/06/what-are-the-main-criticisms-of-the-world-bank-and-the-imf/#top

- Raypole, Crystal. (2021). A Savior No One Needs: Unpacking and Overcoming the White Savior Complex. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/white-saviorism

- Abimbola, S and Madhukar, P. (2020). Will global health survive its decolonisation? The Lancet. Vol 396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32417-X

- Attas, R. (n.d.) What is decolonization? What is Indigenization? Queen’s University Centre for Teaching and Learning. https://www.queensu.ca/ctl/sites/webpublish.queensu.ca.ctlwww/files/files/What%20We%20Do/Decolonization%20and%20Indigenization/What%20is%20Decolonization-What%20is%20Indigenization.pdf

- BBC. (2021). The transatlantic slave trade overview. Bitesize BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/z2qj6sg/articles/zfkfn9q

- National Geographic. (2021). European Colonization of North America. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/topics/european-colonization-north-america/?q=&page=1&per_page=25

- Muswellbrook Shire Council. (2020). Initial invasion and colonisation (1788 to 1890). Working with Indigenous Australians First Nations People Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their communities. (http://www.workingwithindigenousaustralians.info/content/History_3_Colonisation.html

- Archibong, B, Sangafowa Coulibaly, B, Okonjo-Iweala, N. (2021). How have the Washington Consensus reforms affected economic performance in sub-Saharan Africa? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2021/02/19/how-have-the-washington-consensus-reforms-affected-economic-performance-in-sub-saharan-africa/