Key Concepts

- Health

- Public Health

- Clinical Medicine

- Global Health

- Epidemiology

- Glo-cal

- One Health

- Indigenous health

- Traditional medicine

- Islamic medicine

Prelim Engagement

1. The eradication of the smallpox virus is one of the greatest global health victories in history. Achieving this milestone required collaborative efforts between and within countries around the world --- including between the United States and the USSR at the height of the Cold War. View this video as your first introduction to the fields of Public and Global Health. In many ways, the success of the Smallpox Eradication Campaign illustrates the very best of what the fields of Public and Global Health aim to achieve. However, as we will learn later in this course and as we have seen throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the fields of Public and Global Health face many challenges. As you watch, reflect on which lessons learned from the Smallpox Eradication Campaign could be applied to current Global Health challenges, including the COVID-19 global pandemic. We hope this Global Health success story gets you excited for the course ahead!

2. So, what exactly do we mean by Public Health? As you watch this short video, reflect on aspects of Public Health you recognized while learning about the Smallpox Eradication Campaign.

3. First Public Health --- now, Global Health? What distinguishes these two fields --- or, are there actually any distinctions at all? This short article outlines the many definitions of the field of Global Health. We will explore these definitions in detail in the section to follow. While reading, reflect on any differences you see between the field of Public Health (from the previous video) and the field of Global Health. Do you see any similarities between the two fields, where they might overlap?

What is global health? [clink on link to short article]

Welcome to the world of Global Health!

It sounds exciting — an entire world to explore!

But what do we even mean by Global Health? You may have heard of the field Public Health as well. Are Public and Global Health the same? Similar, but different? Where does the field of clinical medicine fit in? And why do we even need an entire field dedicated to Global Health?

The COVID-19 pandemic has launched the fields of Public and Global Health to the forefront of our lives — from news headlines to conversations with families and friends to rules, regulations, recommendations and legal battles that drastically altered the rhythms of life — most of the world whether they know it or not has been living Public and Global Health for months. Actually, we’ve always been living Public and Global Health!

But again, what do these terms actually mean?

In this first section, let’s break it all down.

We will start with the definition of health.

Health

Health is fundamental for a good quality of life. Being free from illness or injury directly affects our capacity to enjoy life (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser, 2016).

But how do we define health? Is being healthy only a matter of not being sick or injured? What contributes to our health status as individuals — and why do we see such varying health outcomes between individuals and different populations in our communities, cities, countries and globally?

The World Health Organization, the United Nations agency responsible for health policy formation, response and coordination globally, defined health in 1948 as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” (WHO, n.d.). Does anything strike you about this definition? How do you think social well-being is linked to health? How would you define social well-being for yourself? Do you think everyone around the world would use the same definition?

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity

(World Health Organization, 1948)

We often think of health in terms of sickness and injury — but what other dimensions of well-being do you as an individual, your community and people around the world need to live a full, enjoyable, creative and productive life?

In this course we will explore the many dimensions of health and well-being and what it means to think about health on a global scale. We will discuss the many determinants of health to better understand why we see differences in health outcomes within our own communities, our countries and between geographic and social contexts globally. We will illustrate and animate our conversations around health, health determinants and differences between individual and population health outcomes using examples from around the world.

In this first section, we will discuss a number of key terms and concepts that are foundational to understanding the field of Global Health. We will explore where Global Health ‘fits’ in efforts to address some of the most pressing health challenges and inequities around the world. As the course progresses, your readings will consist of fewer key terms and more illustrative examples. We will ask you to think critically and to ask questions. Our hope is that you leave this course with a new way of seeing and understanding health, the world around you and what we can do as individuals and a global community to increase health equity and work towards social justice around the world.

Public Health

To better understand the field of Global Health, let’s start with an understanding of Public Health…

What is an ‘intervention’?

Throughout this course you will read a number of references to ‘interventions’ – what does that mean?

A health intervention is an action or collection of actions in response to a specific health problem. Health interventions have different aims, some of which could include one or more of the following:

- Assess a health problem (often through research) to understand underlying causes and/or the scope better;

- Promote different health behaviors to improve health outcomes through education or legislation;

- Improve living conditions to enable health improvements;

- Address a health problem through direct action such as training health providers, improving access to health resources or services or distributing medicines or materials.

(WHO, 2018)

Globally, health outcomes are at their best levels ever before in history — people are living longer all around the world, fewer children are dying young and we continue to find ways to address health challenges which were incurable just years ago.

Life expectancy is the most commonly used measure used to describe a population’s health. Historical data shows that global life expectancy has increased drastically over the last couple of centuries, with substantial long-run improvements in all countries around the world (Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser, 2016).

Global Life Expectancy

Advancements in the field of medicine have inarguably made substantial contributions to health gains globally in the last centuries. Think of the video you watched on smallpox. Without vaccine technology, the smallpox virus would almost certainly never have been eradicated. However, most of our major health milestones would have been impossible to achieve without Public Health solutions and actions as well. But what is Public Health? See different definitions for this wide-ranging field below.

Public health is the art and science of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts of society.

(Acheson, 1988; WHO)

Public health researchers, practitioners and educators work with communities and populations. They identify the causes of disease and disability, and implement large scale solutions (also referred to as interventions).

(Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, n.d.)

Public health is committed to justice and equity, especially relating to the achievement of the highest standard of health and well-being.

Public Health is interdisciplinary, encompassing and relying on the knowledge, skills and approaches from a range of disciplines and professions.

(WHO, 2012)

Public health system actors

- Public health agencies at state and local levels

- Healthcare providers

- Public safety agencies

- Human service and charity organizations

- Education and youth development organizations

- Recreation and arts-related organizations

- Economic and philanthropic organizations

- Environmental agencies and organizations

CDC (2020). Original Essential Public Health Services Framework.

Public health systems include “all public, private, and voluntary entities that contribute to the delivery of essential public health services within a jurisdiction” (CDC, 2020).

The ‘actors’ in Public Health systems can be diverse and will vary from context to context. This diversity illustrates the interdisciplinary nature of the field of Public Health itself. From research to policy making, from community health education to connecting populations directly to clinical services, it takes many different people and organizations to make Public Health work.

There are a variety of professional roles and careers within the field of public health. One of these specialty areas you may hear mentioned often is epidemiology.

Epidemiologists study the patterns and causes of disease and illness in different populations.

Epidemiologists use data – both quantitative (statistics) and qualitative (interviews and focus groups) data – to study and identify patterns and causes of diseases. These analyses are used in the formation of public health policy and programming at all levels of public health systems.

Essential Public Health Services

The Ten Essential Public Health Services were created to help define the role and purpose of public health when working within communities (see Figure 1).

There are three major components that these Ten Essential Public Health Services fall into:

- Assessment

- Policy development

- Assurance

Assessment provides the agencies and departments time to look at the health of their community. This gives them time to interpret and share data that was collected within their community.

Policy development uses the known information that was collected during Assessment and implements policies to solve health problems of the community.

Assurance involves public health agencies providing programs that the community needs. Programs may come directly from the agency itself or from external actors (refer to Public Health Systems Actors above). Overall, making sure that their community has the services they need in order to thrive in an healthy environment (Pomeroy, Asante and St. Louis, n.d.).

Now that you know the definition of Public Health, the diversity of actors that can be involved in Public Health activities and how we might categorize those activities — what are some concrete examples of Public Health work in action?

Examples of Public Health in Action

- Identifying ways to curb bullying in schools

- Delivering vitamin A to newborns in developing nations

- Uncovering correlations between kidney function and heart disease

- Examining secondhand tobacco smoke levels and exposure

- Exploring environmental and genetic factors in autism

- Investigating the consequences of antibiotic use in industrial agriculture

- Developing emergency preparedness plans

- Improving technologies that make clean and safe drinking water

- Promoting policies that protect the global environment and sustainable practices

- Using evidence to strengthen family planning, and reproductive health programs and policies

- Quantifying the links between human rights abrogation and poor health

Source: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (n.d.) https://www.jhsph.edu/about/what-is-public-health/

Public Health & Clinical Medicine: Same or Different?

Is Public Health different from the field of clinical medicine? Now that you know how Public Health is defined, read and reflect on the definition of clinical medicine below.

What similarities do you see between the fields of Public Health and clinical medicine? How are the two fields different?

Clinical medicine is focused on the prevention, diagnoses, and treatment of diseases at the individual level

(Fineberg, 2011)

What key terms stood out to you in each definition? Table 1 helps us break down the differences between Public Health and medical approaches to addressing health challenges. As you review the differences between the two fields, note that both fields contribute in interrelated ways to addressing health challenges and improving health overall.

Would health outcomes improve if one field existed in isolation from the other? Probably not. It would be very hard to address major health challenges with just Public Health or clinical medicine alone. Think again of smallpox. Would we have eradicated smallpox without a vaccine from clinical medicine and research? Almost certainly not. But, if we had not had Public Health systems to get the vaccine to populations around the world the vaccine would have been useless!

Table 1. What distinguishes Public Health from Medicine?

| Dimension | Public Health | Clinical Medicine |

| Focus | Populations | Individual |

| Ethical orientation | Public service | Personal service |

| Approach to addressing health challenges | Disease prevention and health promotion for the entire community | Some prevention, but main focus on disease diagnosis and treatment for the individual patient |

| Intervention emphasis | Spectrum of interventions aimed at the environment, human behavior and lifestyle, and medical care | Places predominant emphasis on medical care |

| Foundational scientific perspectives |

|

|

| Integration of social science perspectives* | Social sciences and public policy disciplines an integral part of public health education | Social sciences tend to be an elective part of medical education (though this is changing) |

*The social sciences are defined as “the study of society and the manner in which people behave and influence the world around us” (Economic and Social Research Council, 2021).

Table 2. offers examples of health interventions to address different health challenges from both Public Health and clinical medical perspectives. Again, note the interrelated nature of the two fields — for example, could we prevent the spread of COVID-19 globally with only Public Health or medical actions alone?

Table 2. Addressing health challenges from Public Health and Medical perspectives

| Health challenge | Public Health actions | Clinical Medical actions |

| Reducing child deaths from diarrhea |

|

|

| Preventing the spread of COVID-19 via vaccination |

|

|

| Preventing motorcycle deaths |

|

|

Public Health & Clinical Interventions

What is social science? How do social science perspectives inform public and global health?

Throughout our discussions we will reference the social sciences, including health social sciences. We will look at how social science perspectives inform our understanding of health challenges in the fields of public and global health and how we use social science perspectives in these fields to address health challenges.

Watch this video: What is social science?

In the short videos below, can you recognize examples of Public Health interventions? What about clinical medical interventions? What distinguishes the two? Where do the lines between Public Health and clinical medicine blur?

Taking it global

We’ve covered a lot of information so far —

✔ How do we define health?

✔ What is Public Health?

✔ What are examples of different Public Health actions?

✔ How do Public Health and clinical medicine differ?

But we still have not answered our original question — what is Global Health? Let’s do that now!

As you saw with Public Health, the field of Global Health is broad and touches on a number of different subject areas and topics of interest. The field of Global Health is also much younger than the field of Public Health and has changed significantly over time. We will explore the roots, history and evolution of the field of Global Health in more detail in future sections of this course.

See different definitions of this relatively new and ever-evolving field below.

You may also find it interesting to note how Global Health resources created before the COVID-19 pandemic discuss future health challenges — and how much has changed in the world of Global Health since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

Global Health can be most succinctly defined as “collaborative trans-national [transcending national boundaries] research and action for promoting health for all”.

(Beaglehole and Bonita, 2010)

In more detail, we can say that Global Health:

- Is an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide.

- Emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences; and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.

- Places priority on prevention, [but] it also embraces curative, rehabilitative, and other aspects of clinical medicine and the study of basic sciences (Koplan 2009).

What is Global Health?

In more abstract, but very applicable terms Global Health can be understood as…

…an attitude. It is a way of looking at the world. It is about the universal nature of our human predicament. It is a statement about our commitment to health as a fundamental quality of liberty and equity.

(R. Horton to P. Farmer, personal communication, January 29, 2012)

What are some of the most pressing Global Health issues today?

Selection of pressing Global Health issues

- Emerging infectious diseases (ie COVID-19)

- Re-emerging infectious diseases (ie Ebola)

- Causes of maternal mortality

- Eradication of polio

- Tuberculosis

- Malaria

- HIV

- Malnutrition globally, including under- and overnutrition

- Increase in diabetes and heart disease globally

- Distribution of essential medications and vaccinations globally (ie COVID-19 vaccine)

Source: Adapted from Skolnik (2019)

As in Public Health, epidemiologists also work in Global Health to identify and study patterns and causes of diseases related to pressing Global Health issues. These analyses inform health policy and programming on national and global levels.

As you were learning about the fields of Public and Global Health, did you notice some similarities between the two? If you did, well done — there are many similarities between the fields of public and global health. Some might say that global health is just public health on a global scale. Others might say that the distinction between the two fields no longer exists — especially as we continue to respond to and live with a global pandemic.

The blurring of lines between what is distinctly ‘local’ (public health) and ‘global’ (global health) can be described as Glo-cal health.

Glo-cal health

Recognizing the interconnectedness of global + local health dynamics, politics, policies and actions;

Understanding the real consequences the ‘global’ has on our ‘local’ health and how our ‘local’ policies and actions might positively or negatively affect others’ lived realities

(Adapted from Kickbush, 1999)

While public and global health in theory and practice overlap in many ways and our world is becoming ever-more Glo-cal, there are still some important distinctions to draw between the two fields. Table 3 helps us break these similarities and differences down.

Table 3. Comparison of Global Health and Public Health

| Global Health | Public Health | |

| Geographical reach | Focuses on issues that directly or indirectly affect health but that can transcend national boundaries | Focuses on issues that affect the health of the population of a particular community or country |

| Level of cooperation | Often requires global cooperation | Does not usually require global cooperation |

| Individuals or populations | Both prevention in population and clinical care of individuals | Main focus on prevention programmes for populations |

| Health equity and access to health | Focus on health equity among nations, for all people | Focus on health equity within a single nation or community |

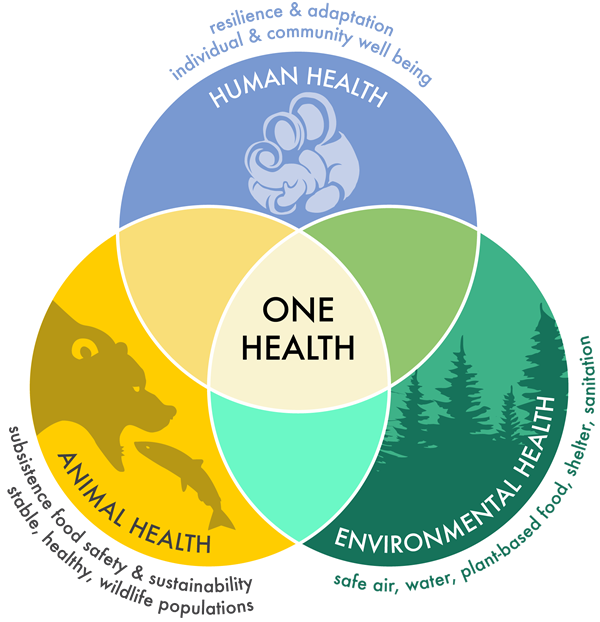

One Health: integrating the health of people, animals & the environment

One particular approach to global health is the field of One Health. Some Global Health actors believe all global health interventions addressing health challenges should adopt a One Health approach.

What do you think?

One Health is the integrative effort of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals, and the environment.

(American Veterinary Medical Association, n.d.)

But why do we need One Health if we already have public and global health? Are they really that different? What does an One Health approach offer us that a ‘classic’ public or global health approach does not?

Watch the short video below of Dr Jakob Zinsstag, a One Health expert from the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel, Switzerland. Dr Zinsstag discusses how a One Health approach to global health challenges can integrate and address the well-being of people, animals and the environment together.

Indigenous Health is Global Health

How do Indigenous communities, peoples and nations self-identify?

Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them.

They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal system…

On an individual basis, an indigenous person is one who belongs to these indigenous populations through self-identification as indigenous (group consciousness) and is recognized and accepted by these populations as one of its members (acceptance by the group). This preserves for these communities the sovereign right and power to decide who belongs to them without external interference.

Excerpt from the Introduction of the United Nations report State of the World’s Indigenous People: Indigenous People’s Access to Health Services UN (2015)

| The United Nations estimates that more than 370 million Indigenous people live across 90 different countries worldwide (UN, 2015). Indigenous peoples around the world share rich histories and practices of health and well-being: from the resurgence of traditional midwifery and child-rearing practices, for example, to the hunting and consumption of local foods; the observance of ceremonies, rites of passage, and end-of-life customs; and the everyday enactment of respectful relations with the natural world, Indigenous peoples across the globe cultivate the health and well-being of individuals, communities and nations. And yet, despite the continuance and resurgence of such practices, Indigenous peoples experience disproportionate health and social problems in comparison to the non-Indigenous peoples living within the same borders (Gracey and King 2009; King, Smith, and Gracey 2009; Smith 1999; United Nations 2009, 2015). Source: Henry, LaVallee, Van Styvendale and Innes (2018) Introduction to Global Indigenous Health. |

It is important to distinguish how Indigenous communities generally understand and frame the concept of health differently from western clinical medicine as well as the definitions of health, Public Health and Global Health we explored above.

When reading the description of Indigenous conceptualizations of health below, note which words and phrases strike you the most.

Does this understanding of health differ greatly from your own or not? What similarities and differences do you see between Indigenous perceptions of health and the western-based descriptions of health, Public Health, Global Health and One Health we explored above?

Also essential to note — by using the term ‘Indigenous’ we in no way mean to erase the incredible diversity within and between Indigenous nations and communities around the world. While Indigenous identity can be defined using the concepts listed above, each Indigenous population has unique historical, socio-cultural and political contexts and practices.

While we cannot within the context of this survey course give space to each of the 370+ million Indigenous peoples around the world, we will offer students narrative case studies of a select number of communities residing on different continents. The grave injustices forced upon Indigenous communities by settler colonialists over the past centuries and which continue today demand exposure — but we will also acknowledge and celebrate Indigenous resistance to these injustices in an attempt to redefine mainstream western narratives and representations of Indigenous people globally.

Indigenous Health

Indigenous peoples’ concept of health and survival is both a collective and an individual inter-generational continuum encompassing a holistic perspective incorporating four distinct shared dimensions of life. These dimensions are the spiritual, the intellectual, physical, and emotional. Linking these four fundamental dimensions, health and survival manifests itself on multiple levels where the past, present, and future co-exist simultaneously

(Committee on Indigenous Health, 1999)

Indigenous Health theories, models, and practices often have a deeply relational character: the well-being of individuals is intimately bound with the well-being of others, both human and other- or more-than-human.

( Henry, LaVallee, Van Styvendale and Innes (2018) Introduction to Global Indigenous Health)

On the framing of Indigenous Health and western biomedicine [clinical medicine]…

Scholarly discussions of health are often dominated by Western biomedical discourse, which focuses on a cure/disease model. Health, in this model, has been and continues to be typically defined as the “absence of disease or illness” (Rootman and Raeburn 1994). As such, health systems and health research are often viewed through a Western Eurocentric lens, which focuses on healing the body from disease and not on the social and environmental factors that inÞuence an individual’s health (Shah 2003). For example, within the field of epidemiology research, health status is still measured by indicators such as incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates. Through the centering of Western biomedical perspectives and understandings, traditional Indigenous knowledges about health and well-being have been ignored. In other cases, Indigenous knowledges—for example, of medicinal plants or healing practices—have been outright stolen and claimed by Western science (Bala and Gheverghese Joseph 2007).

Western indicators do not directly improve our understanding of how socio-political histories shape environmental factors that lead to ill health for Indigenous and other marginalized populations (Singer 2009). In contrast to Western biomedical models focused on the absence of disease as a primary indicator of health, many Indigenous peoples view health, instead, as an interrelated relationship between the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual aspects of the self, as well as the relationship between individuals and their environments (King, Smith, and Gracey 2009; Kuokkanen 2007; Saul 2014).

As a 2009 UN report sets forth, Western health practices often tacitly assume and promote a common heritage, belief system, structure, language, and identity based exclusively on Western medicine, which “does not recognize traditional healing techniques such as song and dance, or traditional training methods for medical practitioners, such as dreams, yet these practices are viewed as integral to the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of illnesses in indigenous health systems” (Cunningham 2009, 175).

This ethnocentric bias results in missed opportunities to understand the complexities of health through myriad perspectives and traditional knowledges connected to particular territories and peoples.

Source: Henry, LaVallee, Van Styvendale and Innes (2018) Introduction to Global Indigenous Health. Pages 10-11. Italics added for emphasis.

The authors of this resource are not and do not claim to be experts in Indigenous Health. It is telling that in our training as public and global health professionals neither of us encountered Indigenous health as an explicit part of our academic and professional training. We welcome any and all additions or suggestions on how to better discuss and feature Indigenous peoples’ histories, stories and resilience in this global health resource.

We will explore resistance and resilience of Indigenous communities facing serious health disparities, the interconnected histories of Indigenous peoples, colonialism, neocolonialism and Indigenous peoples’ health outcomes throughout this course. Our aim is to hold space for the stories of Indigenous people’ history, resilience and health outcomes and illustrate how Indigenous health is an inherent and essential part of Global Health.

Importance and roles of non-western medical knowledge & practice

As highlighted in our brief introduction to Indigenous health above, western clinical medicine and perceptions of health that inform the fields of public and global health are only one way of understanding health, well-being and health care.

People in all regions of the world — including in high income countries — integrate medical knowledge and practices from systems and philosophies other than western clinical medicine into their self-care and medical routines every day. While we do not have the specific expertise or capacity to explore all health knowledge and systems in detail in this course, we will discuss the roles, use and necessary considerations of traditional medicinein the fields of Public and Global Health.

We offer basic definitions of traditional medicine and traditional Arabic and Islamic medicine below as well as links to further readings under Supplementary Resources in this section.

Traditional Medicine “is the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness”

(WHO, n.d.).

Traditional Arabic & Islamic Medicine is “a system of healing practiced since antiquity in the Arab world within the context of religious influences of Islam. It is comprised of medicinal herbs, dietary practices, mind-body practices, spiritual healing and applied therapy whereby many of these elements reflect an enduring interconnectivity between Islamic medical and prophetic influences as well as regional healing practices emerging from specific geographical and cultural origins”

(Al-Rawi & Fetters, 2012)

So there you have it — but that is just scratching the surface of the huge question ‘what is Global Health?’ Through each section of this course we will explore a different dimension of this vast, exciting and often complicated field. We look forward to this adventure together!

Supplementary Resources

- Northern and Indigenous Health and Healthcare (OER Textbook):

- Public Health Achievements

- Defining Global Health

- Traditional Medicine

- Islamic Medicine

References

Alrawi, S. N., & Fetters, M. D. (2012). Traditional arabic & islamic medicine: a conceptual model for clinicians and researchers. Global Journal of Health Science. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v4n3p164

American Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). One Health- What is it?. https://www.avma.org/one-health-what-one-health

Beaglehole and Bonita (2010). What is Global Health? Global Health Action. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

CDC Foundation. (n.d.). What is Public Health?. https://www.cdcfoundation.org/what-public-health

CDC (2020). Original Essential Public Health Services Framework. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/originalessentialhealthservices.html. Accessed May 18 2021.

Committee on Indigenous Health. (1999). Report of the International Consultation on the Health of Indigenous Peoples.

Economic and Social Research Council (2021). https://esrc.ukri.org/about-us/what-is-social-science/ Accessed on 5.17.21.

Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser (2016) – “Global Health”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/health-meta‘ [Online Resource]

Fineberg, H. V. (2011). Public health and medicine: Where the twain shall meet. In American Journal of Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.07.013

Henry, LaVallee, Van Styvendale and Innes (2018) Global Indigenous Health. Arizona University Press.

Ingram, R. C., Miron, E., & Scutchfield, D. F. (2012). From service provision to function based performance – perspectives on public health systems from the USA and Israel. NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3560218/

Institute of Medicine. (1998). America’s vital interest in global health: Protecting our people, enhancing our economy, and advancing our international interests. National Academies Press (US).

John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (n.d). What is Public Health? https://www.jhsph.edu/about/what-is-public-health/ Accessed on 5.17.21.

Kickbusch, I. (1999). Global + local = glocal public health. In Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.53.8.451

Koplan, J. (2009). Towards a common definition of Global Health. The Lancet. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140- 6736(09)60332-9

Pomeroy, K., Asante, I., St.Louis, J. (n.d.) Models and Mechanisms of Public Health. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-buffalo-environmentalhealth/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Skolnik, R. (2019). Global Health 101 Fourth Edition.

United Nations (2015) State of the World’s Indigenous People: Indigenous people’s access to health services. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/2016/Docs-updates/SOWIP_Health.pdf. Accessed May 18 2021.

World Health Organization. (1948). Preamble to the Constitution of WHO as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19 June – 22 July 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of WHO, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. The definition has not been amended since 1948.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Traditional, complementary and integrative medicine. https://www.who.int/health-topics/traditional-complementary-and-integrative-medicine.

World Health Organization (2012). European Action Plan for Strengthening Public Health Capacities and Services. WHO Europe Regional Office, Denmark. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/171770/RC62wd12rev1-Eng.pdf